Taberer report is a report published in 1907 and composed by Henry Taberer and J. Glenn Leary. [1]

The work demonstrated evidence of male same-sex relationships in gold mines near Johannesburg, South Africa. [2]

Taberer was born on a mission station and was a fluent speaker of the languages used by the local population: he claimed to speak them more fluently than he did English. [3] He was able to use this talent effectively when he became manager of the South African government's Native Labour Bureau and adviser to the Native Recruiting Corporation for the Chamber of Mines at a time of increasing industrial unrest. [3] Leary was another respected official and he worked as a magistrate. [2]

A large disparity between the sexes existed within the Mozambican migrant worker community in South Africa. In 1886, there were 30,000 men but only 90 women of Mozambican descent in the Johannesburg region. [2]

Before the establishment of colonial criminal labour systems, homosexual relationships were not punished. [4]

Taberer and Leary were tasked with researching "mine marriages" between male African miners. Local missionaries had complained about immoralities that happened in the gold mines, and the complaints resulted in the investigation. [1] [2] Taberer coauthored the report with Leary. The report was based on evidence collected during a nine-day period in January 1907. Testimonies were gathered from 54 African and European witnesses. The questions and answers were remarkably explicit about sexual activity and motivations. [5]

A Chopi miner working in the mines explained to Taberer that miners who engaged in homosexual acts with young men tried to avoid contracting a venereal disease. The view is supported by evidence that there were lower rates of venereal disease among Tsonga people compared to those Africans who visited female prostitutes. [5] The report successfully dismissed claims by Reverend Baker that the homosexual relations were violent and formed as formal marriages. [5] Relationships between miners often included sex, but male "wives" also gave domestic services to their partners. [6] [7]

Taberer and Leary proposed several solutions for curtailing homosexual relationships between miners, but they were rejected. For instance, they proposed that large numbers of female wives should be allowed to migrate with the men or that large-scale prostitution should be allowed. Ultimately, only screens around beds were banned throughout all industrial compounds in South Africa. [5]

Taberer's neutrality can be questioned. [5] Taberer and Leary's approach for collecting data minimised the amount of recorded anal sex. [1]

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to people of the opposite sex. It "also refers to a person's sense of identity based on those attractions, related behaviors, and membership in a community of others who share those attractions." Someone who is heterosexual is commonly referred to as straight.

A lesbian is a homosexual woman or girl. The word is also used for women in relation to their sexual identity or sexual behavior, regardless of sexual orientation, or as an adjective to characterize or associate nouns with female homosexuality or same-sex attraction. The concept of "lesbian" to differentiate women with a shared sexual orientation evolved in the 20th century. Throughout history, women have not had the same freedom or independence as men to pursue homosexual relationships, but neither have they met the same harsh punishment as gay men in some societies. Instead, lesbian relationships have often been regarded as harmless, unless a participant attempts to assert privileges traditionally enjoyed by men. As a result, little in history was documented to give an accurate description of how female homosexuality was expressed. When early sexologists in the late 19th century began to categorize and describe homosexual behavior, hampered by a lack of knowledge about homosexuality or women's sexuality, they distinguished lesbians as women who did not adhere to female gender roles. They classified them as mentally ill—a designation which has been reversed since the late 20th century in the global scientific community.

Sexual orientation is an enduring personal pattern of romantic attraction or sexual attraction to persons of the opposite sex or gender, the same sex or gender, or to both sexes or more than one gender. Patterns are generally categorized under heterosexuality, homosexuality, and bisexuality, while asexuality is sometimes identified as the fourth category.

Societal attitudes towards same-sex relationships have varied over time and place. Attitudes to male homosexuality have varied from requiring males to engage in same-sex relationships to casual integration, through acceptance, to seeing the practice as a minor sin, repressing it through law enforcement and judicial mechanisms, and to proscribing it under penalty of death. In addition, it has varied as to whether any negative attitudes towards men who have sex with men have extended to all participants, as has been common in Abrahamic religions, or only to passive (penetrated) participants, as was common in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. Female homosexuality has historically been given less acknowledgment, explicit acceptance, and opposition.

Intercrural sex, which is also known as coitus interfemoris, thigh sex, thighing, thighjob and interfemoral sex, is a type of non-penetrative sex in which the penis is placed between the receiving partner's thighs and friction is generated via thrusting. It was a common practice in ancient Greek society prior to the early centuries AD, and was frequently discussed by writers and portrayed in artwork such as vases. It later became subject to sodomy laws and became increasingly seen as contemptible. In the 17th century, intercrural sex was featured in several works of literature and it took cultural prominence, being seen as a part of male-on-male sexual habits following the trial and execution of Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven, in 1631.

Gay men are male homosexuals. Some bisexual and homoromantic men may dually identify as gay and a number of gay men also identify as queer. Historic terminology for gay men has included inverts and uranians.

LGBTQ history dates back to the first recorded instances of same-sex love, diverse gender identities, and sexualities in ancient civilizations, involving the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) peoples and cultures around the world. What survives after many centuries of persecution—resulting in shame, suppression, and secrecy—has only in more recent decades been pursued and interwoven into more mainstream historical narratives.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in Zimbabwe face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBTQ residents. Since 1995, the Government of Zimbabwe has carried out campaigns against LGBT rights. Sodomy is classified as unlawful sexual conduct and defined in the Criminal Code as either anal sexual intercourse or any "indecent act" between consenting adults. Since 1995, the government has carried out campaigns against both homosexual men and women.

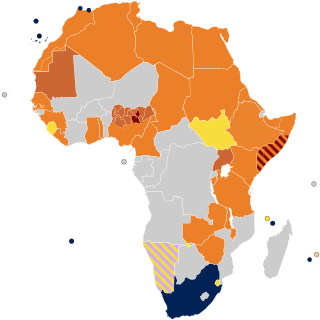

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Africa are generally poor in comparison to the Americas, Western Europe and Oceania.

A same-sex relationship is a romantic or sexual relationship between people of the same sex. Same-sex marriage refers to the institutionalized recognition of such relationships in the form of a marriage; civil unions may exist in countries where same-sex marriage does not.

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, to more than one gender, or to both people of the same gender and different genders. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, which is also known as pansexuality.

Corrective rape, also called curative rape or homophobic rape, is a hate crime in which somebody is raped because of their perceived sexual orientation. The common intended consequence of the rape, as claimed by the perpetrator, is to turn the person heterosexual.

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBTQ topics:

Sexual diversity or gender and sexual diversity (GSD), refers to all the diversities of sex characteristics, sexual orientations and gender identities, without the need to specify each of the identities, behaviors, or characteristics that form this plurality.

The Forest Town raid was a 1966 police raid that targeted LGBT people in Forest Town, Gauteng. The raid led to proposed anti-homosexuality legislation in South Africa. It also helped coalesce the queer community in South Africa.

Acquired homosexuality is the idea that homosexuality can be spread, either through sexual seduction or recruitment by homosexuals, or through exposure to media depicting homosexuality. According to this belief, any child or young person could become homosexual if exposed to it; conversely, through conversion therapy, a homosexual person could be made straight.

Lesotho does not recognise same-sex marriages or civil unions. The Marriage Act, 1974 does not recognise same-sex unions.

Zimbabwe does not recognize same-sex marriages or civil unions. The Marriages Act does not recognise same-sex marriage, and civil partnerships are only available to opposite-sex couples. The Constitution of Zimbabwe explicitly prohibits same-sex marriages.

Botswana does not recognize same-sex marriages or civil unions. The Marriage Act, 2001 does not recognize same-sex unions.

Mozambique does not recognize same-sex marriages or civil unions. The Family Code of Mozambique recognises de facto unions but only for opposite-sex couples and bans same-sex marriage.