Aerovías de México, S.A. de C.V. operating as Aeroméxico, is the flag carrier of Mexico, based in Mexico City. It operates scheduled services to more than 90 destinations in Mexico; North, South and Central America; the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia. Its main base and hub is located in Mexico City, with secondary hubs in Guadalajara and Monterrey. The headquarters is in the Torre MAPFRE on Paseo de la Reforma.

General Mariano Escobedo International Airport, simply known as Monterrey International Airport, is an international airport located in Apodaca, Nuevo León, Mexico serving Greater Monterrey. It operates flights to Mexico, the United States, Canada, Latin America, Asia and Europe. The airport serves as the main hub for Viva Aerobus, Magnicharters, and the regional carrier Aerus. It is also a focus city for Volaris, Aeromexico Connect, and the regional airline TAR Aerolíneas. The airport also serves cargo and charter flights, hosts facilities for Mexican Airspace Navigation Services, and facilitates various tourism-related activities, flight training, and general aviation. Monterrey Airport is operated by Grupo Aeroportuario Centro Norte OMA and it is named after General Mariano Escobedo, a prominent military figure born in Nuevo León.

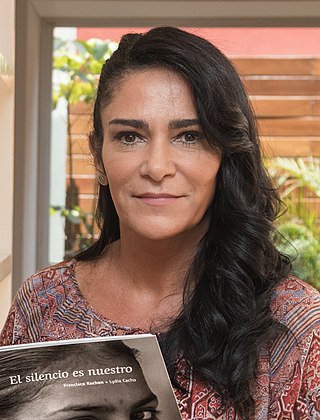

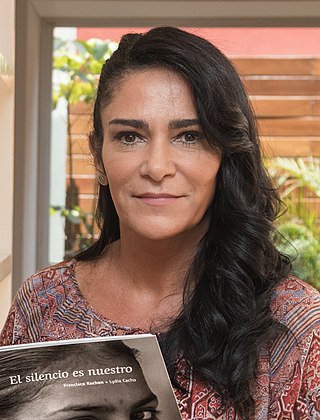

Lydia María Cacho Ribeiro is a Mexican journalist, feminist, and human rights activist. Described by Amnesty International as "perhaps Mexico's most famous investigative journalist and women's rights advocate", Cacho's reporting focuses on violence against and sexual abuse of women and children.

The status of women in Argentina has changed significantly following the return of democracy in 1983; and they have attained a relatively high level of equality. In the Global Gender Gap Report prepared by the World Economic Forum in 2009, Argentine women ranked 24th among 134 countries studied in terms of their access to resources and opportunities relative to men. They enjoy comparable levels of education, and somewhat higher school enrollment ratios than their male counterparts. They are well integrated in the nation's cultural and intellectual life, though less so in the nation's economy. Their economic clout in relation to men is higher than in most Latin American countries, however, and numerous Argentine women hold top posts in the Argentine corporate world; among the best known are María Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat, former CEO and majority stakeholder of Loma Negra, the nation's largest cement manufacturer, and Ernestina Herrera de Noble, director of Grupo Clarín, the premier media group in Argentina.

Feminism in Egypt has involved a number of social and political groups throughout its history. Although Egypt has in many respects been a forerunner in matters of reform particularly "in developing movements of nationalism, of resistance to imperialism and of feminism," its development in fighting for equality for women and their rights has not been easy.

Sylvia Rosila Tamale is a Ugandan academic, and human rights activist in Uganda. She was the first woman dean in the law faculty at Makerere University, Uganda.

Change.org is a website which allows users to create and sign petitions in an attempt to advance various social causes by raising awareness and influencing decision-makers. The site is a US-based for-profit company and claims to have nearly 500 million users as of December 2022. Petitions often focus on causes such as general justice, economic justice, criminal justice, human rights, education, environmental protection, animal rights, health, and sustainable food.

Women in Malaysia receive support from the Malaysian government concerning their rights to advance, to make decisions, to health, education and social welfare, and to the removal of legal obstacles. The Malaysian government has ensured these factors through the establishment of Ministry of National Unity and Social Development in 1997. This was followed by the formation of the Women's Affairs Ministry in 2001 to recognise the roles and contributions of Malaysian women.

Feminist views on transgender topics vary widely.

Feminism in Mexico is the philosophy and activity aimed at creating, defining, and protecting political, economic, cultural, and social equality in women's rights and opportunities for Mexican women. Rooted in liberal thought, the term feminism came into use in late nineteenth-century Mexico and in common parlance among elites in the early twentieth century. The history of feminism in Mexico can be divided chronologically into a number of periods with issues. For the conquest and colonial eras, some figures have been re-evaluated in the modern era and can be considered part of the history of feminism in Mexico. At the time of independence in the early nineteenth century, there were demands that women be defined as citizens. The late nineteenth century saw the explicit development of feminism as an ideology. Liberalism advocated secular education for both girls and boys as part of a modernizing project, and women entered the workforce as teachers. Those women were at the forefront of feminism, forming groups that critiqued existing treatment of women in the realms of legal status, access to education, and economic and political power. More scholarly attention is focused on the Revolutionary period (1915–1925), although women's citizenship and legal equality were not explicitly issues for which the revolution was fought. The Second Wave and the post-1990 period have also received considerable scholarly attention. Feminism has advocated for the equality of men and women, but middle-class women took the lead in the formation of feminist groups, the founding of journals to disseminate feminist thought, and other forms of activism. Working-class women in the modern era could advocate within their unions or political parties. The participants in the Mexico 68 clashes who went on to form that generation's feminist movement were predominantly students and educators. The advisers who established themselves within the unions after the 1985 earthquakes were educated women who understood the legal and political aspects of organized labor. What they realized was that to form a sustained movement and attract working-class women to what was a largely middle-class movement, they needed to utilize workers' expertise and knowledge of their jobs to meld a practical, working system. In the 1990s, women's rights in indigenous communities became an issue, particularly in the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas. Reproductive rights remain an ongoing issue, particularly since 1991, when the Catholic Church in Mexico was no longer constitutionally restricted from being involved in politics.

Gamergate or GamerGate (GG) was a loosely organized misogynistic online harassment campaign and a right-wing backlash against feminism, diversity, and progressivism in video game culture. It was conducted using the hashtag "#Gamergate" primarily in 2014 and 2015. Gamergate targeted women in the video game industry, most notably feminist media critic Anita Sarkeesian and video game developers Zoë Quinn and Brianna Wu.

2014 was described as a watershed year for women's rights, by newspapers such as The Guardian. It was described as a year in which women's voices acquired greater legitimacy and authority. Time magazine said 2014 "may have been the best year for women since the dawn of time". However, The Huffington Post called it "a bad year for women, but a good year for feminism". San Francisco writer Rebecca Solnit argued that it was "a year of feminist insurrection against male violence" and a "lurch forward" in the history of feminism, and The Guardian said the "globalisation of protest" at violence against women was "groundbreaking", and that social media had enabled a "new version of feminist solidarity".

CitizenGO is an ultra-conservative advocacy group founded in Madrid, Spain, in 2013 by the ultra-Catholic and far-right HazteOir organization, a similar Spanish platform that has been dedicated to the fight against "gender ideology" since 2001.

Fourth-wave feminism is a feminist movement that began around the early 2010s and is characterized by a focus on the empowerment of women, the use of internet tools, and intersectionality. The fourth wave seeks greater gender equality by focusing on gendered norms and the marginalization of women in society.

Chairo is a pejorative epithet that originated in Mexico to describe an individual who holds a far-left ideology, specifically any person who thoughtlessly defends, idolizes, and fawns over a populist politician and demagogue with an attitude similar to that of a religious fanatic.

Melissa Ede (25 September 1960 – 11 May 2019) was an English transgender rights campaigner and social media personality. Ede knew that she was transgender from an early age. Her gender reassignment surgery was completed in 2011 and she subsequently received media attention.

Men Going Their Own Way is an anti-feminist, misogynistic, mostly online community advocating for men to separate themselves from women and society, which they believe has been corrupted by feminism. The community is a part of the manosphere, a collection of anti-feminist websites and online communities that also includes the men's rights movement, incels, and pickup artists.

Raquel Ramírez Salgado is a Mexican researcher, communicator, feminist and women's rights activist.

Mexico has one of the world's highest femicide rates, with as many as 3% of murder victims being classified as femicides. In 2021, approximately 1,000 femicides took place, out of 34,000 total murder victims. Ciudad Juárez, in Chihuahua, has one of the highest rates of femicide within the country. As of 2023, Colima State in Mexico has the highest rate of femicide, with over 4 out of every 100,000 women were murdered because of their gender. Morelos state and Campeche state were the following in terms of highest rates of femicide by 2023.