Burrhus Frederic Skinner was an American psychologist, behaviorist, author, inventor, and social philosopher. Considered the father of Behaviorism, he was the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology at Harvard University from 1958 until his retirement in 1974.

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of mental processes such as attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and reasoning.

Teleology or finality is a reason or an explanation for something which serves as a function of its end, its purpose, or its goal, as opposed to something which serves as a function of its cause.

John Broadus Watson was an American psychologist who popularized the scientific theory of behaviorism, establishing it as a psychological school. Watson advanced this change in the psychological discipline through his 1913 address at Columbia University, titled Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It. Through his behaviorist approach, Watson conducted research on animal behavior, child rearing, and advertising, as well as conducting the controversial "Little Albert" experiment and the Kerplunk experiment. He was also the editor of Psychological Review from 1910 to 1915. A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Watson as the 17th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.

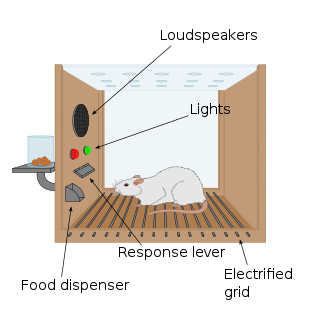

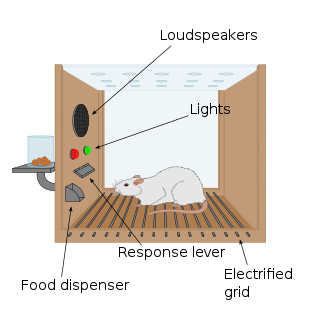

Operant conditioning, also called instrumental conditioning, is a learning process where behaviors are modified through the association of stimuli with reinforcement or punishment. In it, operants—behaviors that affect one's environment—are conditioned to occur or not occur depending on the environmental consequences of the behavior.

An operant conditioning chamber is a laboratory apparatus used to study animal behavior. The operant conditioning chamber was created by B. F. Skinner while he was a graduate student at Harvard University. The chamber can be used to study both operant conditioning and classical conditioning.

In reinforcement theory, it is argued that human behavior is a result of "contingent consequences" to human actions The publication pushes forward the idea that "you get what you reinforce" This means that behavior when given the right types of reinforcers can change employee behavior for the better and negative behavior can be weeded out.

Radical behaviorism is a "philosophy of the science of behavior" developed by B. F. Skinner. It refers to the philosophy behind behavior analysis, and is to be distinguished from methodological behaviorism—which has an intense emphasis on observable behaviors—by its inclusion of thinking, feeling, and other private events in the analysis of human and animal psychology. The research in behavior analysis is called the experimental analysis of behavior and the application of the field is called applied behavior analysis (ABA), which was originally termed "behavior modification."

The experimental analysis of behavior is a science that studies the behavior of individuals across a variety of species. A key early scientist was B. F. Skinner who discovered operant behavior, reinforcers, secondary reinforcers, contingencies of reinforcement, stimulus control, shaping, intermittent schedules, discrimination, and generalization. A central method was the examination of functional relations between environment and behavior, as opposed to hypothetico-deductive learning theory that had grown up in the comparative psychology of the 1920–1950 period. Skinner's approach was characterized by observation of measurable behavior which could be predicted and controlled. It owed its early success to the effectiveness of Skinner's procedures of operant conditioning, both in the laboratory and in behavior therapy.

Behaviorism is a systematic approach to understanding the behavior of humans and other animals. It assumes that behavior is either a reflex evoked by the pairing of certain antecedent stimuli in the environment, or a consequence of that individual's history, including especially reinforcement and punishment contingencies, together with the individual's current motivational state and controlling stimuli. Although behaviorists generally accept the important role of heredity in determining behavior, they focus primarily on environmental events.

The psychology of learning refers to theories and research on how individuals learn. There are many theories of learning. Some take on a more behaviorist approach which focuses on inputs and reinforcements. Other approaches, such as theories related to neuroscience and social cognition, focus more on how the brain's organization and structure influence learning. Some psychological approaches, such as social constructivism, focus more on one's interaction with the environment and with others. Other theories, such as those related to motivation, like the growth mindset, focus more on individuals' perceptions of ability.

Self-control, an aspect of inhibitory control, is the ability to regulate one's emotions, thoughts, and behavior in the face of temptations and impulses. As an executive function, it is a cognitive process that is necessary for regulating one's behavior in order to achieve specific goals.

Behavior modification is an early approach that used respondent and operant conditioning to change behavior. Based on methodological behaviorism, overt behavior was modified with consequences, including positive and negative reinforcement contingencies to increase desirable behavior, or administering positive and negative punishment and/or extinction to reduce problematic behavior. It also used Flooding desensitization to combat phobias.

In psychology, mentalism refers to those branches of study that concentrate on perception and thought processes, for example: mental imagery, consciousness and cognition, as in cognitive psychology. The term mentalism has been used primarily by behaviorists who believe that scientific psychology should focus on the structure of causal relationships to reflexes and operant responses or on the functions of behavior.

Howard Rachlin (1935–2021) was an American psychologist and the founder of teleological behaviorism. He was Emeritus Research Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology at Stony Brook University in New York. His initial work was in the quantitative analysis of operant behavior in pigeons, on which he worked with William M. Baum, developing ideas from Richard Herrnstein's matching law. He subsequently became one of the founders of Behavioral Economics.

In behavioral psychology, stimulus control is a phenomenon in operant conditioning that occurs when an organism behaves in one way in the presence of a given stimulus and another way in its absence. A stimulus that modifies behavior in this manner is either a discriminative stimulus (Sd) or stimulus delta (S-delta). Stimulus-based control of behavior occurs when the presence or absence of an Sd or S-delta controls the performance of a particular behavior. For example, the presence of a stop sign (S-delta) at a traffic intersection alerts the driver to stop driving and increases the probability that "braking" behavior will occur. Such behavior is said to be emitted because it does not force the behavior to occur since stimulus control is a direct result of historical reinforcement contingencies, as opposed to reflexive behavior that is said to be elicited through respondent conditioning.

Psychological behaviorism is a form of behaviorism — a major theory within psychology which holds that generally human behaviors are learned — proposed by Arthur W. Staats. The theory is constructed to advance from basic animal learning principles to deal with all types of human behavior, including personality, culture, and human evolution. Behaviorism was first developed by John B. Watson (1912), who coined the term "behaviorism," and then B. F. Skinner who developed what is known as "radical behaviorism." Watson and Skinner rejected the idea that psychological data could be obtained through introspection or by an attempt to describe consciousness; all psychological data, in their view, was to be derived from the observation of outward behavior. The strategy of these behaviorists was that the animal learning principles should then be used to explain human behavior. Thus, their behaviorisms were based upon research with animals.

George W. Ainslie is an American psychiatrist, psychologist and behavioral economist.

The history of evolutionary psychology began with Charles Darwin, who said that humans have social instincts that evolved by natural selection. Darwin's work inspired later psychologists such as William James and Sigmund Freud but for most of the 20th century psychologists focused more on behaviorism and proximate explanations for human behavior. E. O. Wilson's landmark 1975 book, Sociobiology, synthesized recent theoretical advances in evolutionary theory to explain social behavior in animals, including humans. Jerome Barkow, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby popularized the term "evolutionary psychology" in their 1992 book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and The Generation of Culture. Like sociobiology before it, evolutionary psychology has been embroiled in controversy, but evolutionary psychologists see their field as gaining increased acceptance overall.

Social determinism is the theory that social interactions alone determine individual behavior.