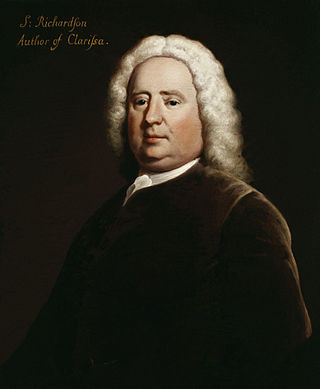

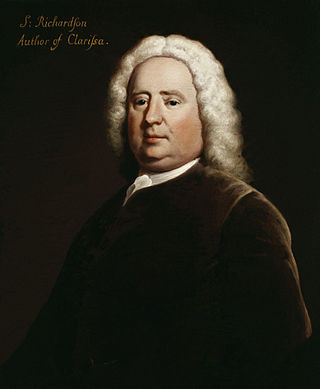

Samuel Richardson was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady (1748) and The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753). He printed almost 500 works, including journals and magazines, working periodically with the London bookseller Andrew Millar. Richardson had been apprenticed to a printer, whose daughter he eventually married. He lost her along with their six children, but remarried and had six more children, of whom four daughters reached adulthood, leaving no male heirs to continue the print shop. As it ran down, he wrote his first novel at the age of 51 and joined the admired writers of his day. Leading acquaintances included Samuel Johnson and Sarah Fielding, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne, and the theologian and writer William Law, whose books he printed. At Law's request, Richardson printed some poems by John Byrom. In literature, he rivalled Henry Fielding; the two responded to each other's literary styles.

Amelia Opie was an English author who published numerous novels in the Romantic period up to 1828. A Whig supporter and Bluestocking, Opie was also a leading abolitionist in Norwich, England. Hers was the first of 187,000 names presented to the British Parliament on a petition from women to stop slavery.

The Silver Chair is a children's portal fantasy novel by C. S. Lewis, published by Geoffrey Bles in 1953. It was the fourth published of seven novels in The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956); it is volume six in recent editions, which are sequenced according to Narnian history. Like the others, it was illustrated by Pauline Baynes and her work has been retained in many later editions.

Theodora Sarah Orne Jewett was an American novelist, short story writer and poet, best known for her local color works set along or near the coast of Maine. Jewett is recognized as an important practitioner of American literary regionalism.

Sarah Fielding was an English author and sister of the novelist Henry Fielding. She wrote The Governess, or The Little Female Academy (1749), thought to be the first novel in English aimed expressly at children. Earlier she had success with her novel The Adventures of David Simple (1744).

Elizabeth Inchbald was an English novelist, actress, dramatist, and translator. Her two novels, A Simple Story and Nature and Art, have received particular critical attention.

Jane West, was an English novelist who published as Prudentia Homespun and Mrs. West. She also wrote conduct literature, poetry and educational tracts.

Immersion journalism or immersionism is a style of journalism similar to gonzo journalism. In the style, journalists immerse themselves in a situation and with the people involved. The final product tends to focus on the experience, not the writer.

The Stars' Tennis Balls is a psychological thriller novel by Stephen Fry, first published in 2000. In the United States, the title was changed to Revenge. The story is a modern adaptation of Alexandre Dumas's 1844 novel The Count of Monte Cristo, which was in turn based on a contemporary legend.

In 1752, Henry Fielding started a "paper war", a long-term dispute with constant publication of pamphlets attacking other writers, between the various authors on London's Grub Street. Although it began as a dispute between Fielding and John Hill, other authors, such as Christopher Smart, Bonnell Thornton, William Kenrick, Arthur Murphy and Tobias Smollett, were soon dedicating their works to aid various sides of the conflict.

Jane Collier was an English novelist best known for her book An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting (1753). She also collaborated with Sarah Fielding on her only other surviving work The Cry (1754).

An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting was a conduct book written by Jane Collier and published in 1753. The Essay was Collier's first work, and operates as a satirical advice book on how to nag. It was modelled after Jonathan Swift's satirical essays, and is intended to "teach" a reader the various methods for "teasing and mortifying" one's acquaintances. It is divided into two sections that are organised for "advice" to specific groups, and it is followed by "General Rules" for all people to follow.

Mary Collier was an English poet, perhaps best known for The Woman's Labour, a poem described by one commentator as a "plebeian female georgic that is also a protofeminist polemic."

Love in Several Masques is a play by Henry Fielding that was first performed on 16 February 1728 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The moderately received play comically depicts three lovers trying to pursue their individual beloveds. The beloveds require their lovers to meet their various demands, which serves as a means for Fielding to introduce his personal feelings on morality and virtue. In addition, Fielding introduces criticism of women and society in general.

The Letter Writers Or, a New Way to Keep a Wife at Home is a play by Henry Fielding and was first performed on 24 March 1731 at Haymarket with its companion piece The Tragedy of Tragedies. It is about two merchants who strive to keep their wives faithful. Their efforts are unsuccessful, however, until they catch the man who their wives are cheating with.

The Lottery is a play by Henry Fielding and was a companion piece to Joseph Addison's Cato. As a ballad opera, it contained 19 songs and was a collaboration with Mr Seedo, a musician. It first ran on 1 January 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The play tells the story of a man in love with a girl. She claims she has won a lottery, however, making another man pursue her for the fortune and forcing her original suitor to pay off the other for her hand in marriage, though she does not win.

Fryniwyd Tennyson Jesse Harwood was an English criminologist, journalist and author.

The Ware Case is a 1938 British drama film directed by Robert Stevenson and starring Clive Brook, Jane Baxter and Barry K. Barnes. It is an adaptation of the play The Ware Case (1915) by George Pleydell Bancroft, which had previously been made into two silent films, in 1917 and 1928. It had been a celebrated stage vehicle for Sir Gerald Du Maurier. The film was made at Ealing Studios with stately home exteriors shot in the grounds of Pinewood. Oscar Friedrich Werndorff worked as set designer.

Le foto proibite di una signora per bene, also known as Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, is a 1970 giallo film directed by Luciano Ercoli. Written by Ernesto Gastaldi and Mahnahén Velasco, the film stars Pier Paolo Capponi, Simon Andreu and Dagmar Lassander. The film, featuring a score written by Ennio Morricone, has received mixed to positive reviews from critics.

Lady Barbara Montague was a British philanthropist and charity worker, who sponsored programs to assist primarily poor women. As an unmarried woman, and due to illness unable to live with family, she created an alternate family situation that allowed her independence. Joining a community of women in Bath, the group pooled their resources to provide support for each other and others in their community. Upon her death, she left bequests to continue providing for those who had been important in caring for her in her lifetime.