Related Research Articles

Benjamin Jonson was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence on English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Fox, The Alchemist (1610) and Bartholomew Fair (1614) and for his lyric and epigrammatic poetry. He is regarded as "the second most important English dramatist, after William Shakespeare, during the reign of James I."

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1616.

Grim the Collier of Croyden; or, The Devil and his Dame: with the Devil and Saint Dunston is a seventeenth-century play of uncertain authorship, first published in 1662. The play's title character is an established figure of the popular culture and folklore of the time who appeared in songs and stories – a body of lore the play draws upon. The London coal and charcoal industry was centred on Croydon, to the south of London in Surrey; the original Grimme or Grimes has been claimed to be a real individual, but evidence for this is not forthcoming.

John Marston was an English playwright, poet and satirist during the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods. His career as a writer lasted only a decade. His work is remembered for its energetic and often obscure style, its contributions to the development of a distinctively Jacobean style in poetry, and its idiosyncratic vocabulary.

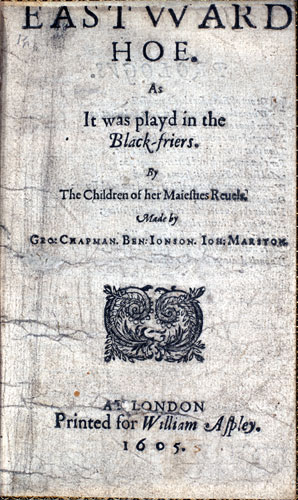

Eastward Hoe or Eastward Ho! is an early Jacobean-era stage play written by George Chapman, Ben Jonson and John Marston. The play was first performed at the Blackfriars Theatre by a company of boy actors known as the Children of the Queen's Revels in early August 1605, and it was printed in September the same year.

Nathan Field was an English dramatist and actor.

Robert Johnson was an English composer and lutenist of the late Tudor and early Jacobean eras. He is sometimes called "Robert Johnson II" to distinguish him from an earlier Scottish composer. Johnson worked with William Shakespeare providing music for some of his later plays.

Every Man in His Humour is a 1598 play by the English playwright Ben Jonson. The play belongs to the subgenre of "humours comedy", in which each major character is dominated by an over-riding humour or obsession.

The Farmer's Curst Wife is a traditional English language folk song listed as Child ballad number 278 and number 160 in the Roud Folk Song Index.

Epicœne, or The Silent Woman, also known as Epicene, is a comedy by Renaissance playwright Ben Jonson. The play is about a man named Dauphine, who creates a scheme to get his inheritance from his uncle Morose. The plan involves setting Morose up to marry Epicoene, a boy disguised as a woman. It was originally performed by the Blackfriars Children, or Children of the Queen's Revels, a group of boy players, in 1609. Excluding its two prologues, the play is written entirely in prose.

Richard Robinson was an actor in English Renaissance theatre and a member of Shakespeare's company the King's Men.

The New Inn, or The Light Heart is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy by English playwright and poet Ben Jonson.

Cynthia's Revels, or The Fountain of Self-Love is a late Elizabethan stage play, a satire written by Ben Jonson. The play was one element in the Poetomachia or War of the Theatres between Jonson and rival playwrights John Marston and Thomas Dekker.

The Staple of News is an early Caroline era play, a satire by Ben Jonson. The play was first performed in late 1625 by the King's Men at the Blackfriars Theatre, and first published in 1631.

Ben Jonson collected his plays and other writings into a book he titled The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. In 1616 it was printed in London in the form of a folio. Second and third editions of his works were published posthumously in 1640 and 1692.

The Devil's Law Case is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by John Webster, and first published in 1623.

Richard Meighen was a London publisher of the Jacobean and Caroline eras. He is noted for his publications of plays of English Renaissance drama; he published the second Ben Jonson folio of 1640/41, and was a member of the syndicate that issued the Second Folio of Shakespeare's collected plays in 1632.

Holland's Leaguer is a Caroline stage play, a comedy written by Shackerley Marmion. It premiered onstage in 1631 and was first published in 1632. The play was a popular success and a scandal in its own day—scandalous because it dealt with a well-known London brothel, Holland's Leguer.

The idea of making a deal with the devil has appeared many times in works of popular culture. These pacts with the Devil can be found in many genres, including: books, music, comics, theater, movies, TV shows and games. When it comes to making a contract with the Devil, they all share the same prevailing desire, a mortal wants some worldly good for their own selfish gain, but in exchange, they must give up their soul for eternity.

Cupid's Whirligig, by Edward Sharpham (1576-1608), is a city comedy set in London about a husband that suspects his wife of having affairs with other men and is consumed with irrational jealousy. It was first published in quarto in 1607, entered in the Stationer's Register with the name "A Comedie called Cupids Whirlegigge." It was performed that year by the Children of the King's Revels in the Whitefriars Theatre where Ben Jonson's Epicene was also said to have been performed.

References

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Evans, Robert C. Jonson and the Context of His Time. Lewisburg, PA, Bucknell University Press, 1994.

- Johnson, William Savage, ed. The Devil is an Ass. New York, Henry Holt, 1905.

- Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. The New Intellectuals: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama. Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1977.