Related Research Articles

Daniel Clement Dennett III was an American philosopher and cognitive scientist. His research centered on the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science.

Materialism is a form of philosophical monism which holds that matter is the fundamental substance in nature, and that all things, including mental states and consciousness, are results of material interactions of material things. According to philosophical materialism, mind and consciousness are caused by physical processes, such as the neurochemistry of the human brain and nervous system, without which they cannot exist. Materialism directly contrasts with idealism, according to which consciousness is the fundamental substance of nature.

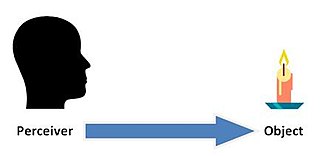

The philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual data, in particular how they relate to beliefs about, or knowledge of, the world. Any explicit account of perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views. Philosophers distinguish internalist accounts, which assume that perceptions of objects, and knowledge or beliefs about them, are aspects of an individual's mind, and externalist accounts, which state that they constitute real aspects of the world external to the individual. The position of naïve realism—the 'everyday' impression of physical objects constituting what is perceived—is to some extent contradicted by the occurrence of perceptual illusions and hallucinations and the relativity of perceptual experience as well as certain insights in science. Realist conceptions include phenomenalism and direct and indirect realism. Anti-realist conceptions include idealism and skepticism. Recent philosophical work have expanded on the philosophical features of perception by going beyond the single paradigm of vision.

Solipsism is the philosophical idea that only one's mind is sure to exist. As an epistemological position, solipsism holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure; the external world and other minds cannot be known and might not exist outside the mind.

In the philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that each and every mental state is constituted solely by its functional role, which means its causal relation to other mental states, sensory inputs, and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

A category mistake, is a semantic or ontological error in which things belonging to a particular category are presented as if they belong to a different category, or, alternatively, a property is ascribed to a thing that could not possibly have that property. An example is a person learning that the game of cricket involves team spirit, and after being given a demonstration of each player's role, asking which player performs the "team spirit".

In the philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, direct or naïve realism, as opposed to indirect or representational realism, are differing models that describe the nature of conscious experiences; out of the metaphysical question of whether the world we see around us is the real world itself or merely an internal perceptual copy of that world generated by our conscious experience.

Daniel Dennett's multiple drafts model of consciousness is a physicalist theory of consciousness based upon cognitivism, which views the mind in terms of information processing. The theory is described in depth in his book, Consciousness Explained, published in 1991. As the title states, the book proposes a high-level explanation of consciousness which is consistent with support for the possibility of strong AI.

Gilbert Ryle was a British philosopher, principally known for his critique of Cartesian dualism, for which he coined the phrase "ghost in the machine." He was a representative of the generation of British ordinary language philosophers who shared Ludwig Wittgenstein's approach to philosophical problems.

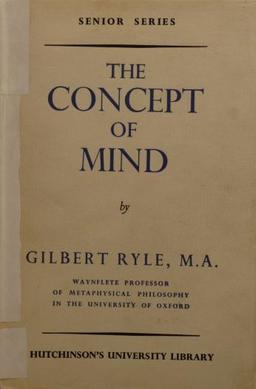

The Concept of Mind is a 1949 book by philosopher Gilbert Ryle, in which the author argues that "mind" is "a philosophical illusion hailing chiefly from René Descartes and sustained by logical errors and 'category mistakes' which have become habitual."

The Ghost in the Machine is a 1967 book about philosophical psychology by Arthur Koestler. The title is a phrase coined by the Oxford philosopher Gilbert Ryle to describe the Cartesian dualist account of the mind–body relationship. Koestler shares with Ryle the view that the mind of a person is not an independent non-material entity, temporarily inhabiting and governing the body. The work attempts to explain humanity's self-destructive tendency in terms of individual and collective functioning, philosophy, and overarching, cyclical political–historical dynamics, peaking in the nuclear weapons arena.

David Malet Armstrong, often D. M. Armstrong, was an Australian philosopher. He is well known for his work on metaphysics and the philosophy of mind, and for his defence of a factualist ontology, a functionalist theory of the mind, an externalist epistemology, and a necessitarian conception of the laws of nature.

The "ghost in the machine" is a term originally used to describe and critique the concept of the mind existing alongside and separate from the body. In more recent times, the term has several uses, including the concept that the intellectual part of the human mind is influenced by emotions; and within fiction, for an emergent consciousness residing in a computer.

Anecdotal cognitivism is a method of research using anecdotal, and anthropomorphic evidence through the observation of animal behaviour.

The philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the body and the external world.

The mind–body problem is a philosophical problem concerning the relationship between thought and consciousness in the human mind and body.

Functional psychology or functionalism refers to a psychological school of thought that was a direct outgrowth of Darwinian thinking which focuses attention on the utility and purpose of behavior that has been modified over years of human existence. Edward L. Thorndike, best known for his experiments with trial-and-error learning, came to be known as the leader of the loosely defined movement. This movement arose in the U.S. in the late 19th century in direct contrast to Edward Titchener's structuralism, which focused on the contents of consciousness rather than the motives and ideals of human behavior. Functionalism denies the principle of introspection, which tends to investigate the inner workings of human thinking rather than understanding the biological processes of the human consciousness.

In philosophy of mind, qualia are defined as instances of subjective, conscious experience. The term qualia derives from the Latin neuter plural form (qualia) of the Latin adjective quālis meaning "of what sort" or "of what kind" in relation to a specific instance, such as "what it is like to taste a specific apple — this particular apple now".

In the philosophy of mind, logical behaviorism is the thesis that mental concepts can be explained in terms of behavioral concepts.

Philip Goff is a British author, idealist philosopher, and professor at Durham University whose research focuses on philosophy of mind and consciousness. Specifically, it focuses on how consciousness can be part of the scientific worldview. Goff holds that materialism is incoherent and that dualism leads to "complexity, discontinuity and mystery". Instead, he advocates a "third way", a version of Russellian idealist monism that attempts to account for reality's intrinsic nature by positing that consciousness is a fundamental, ubiquitous feature of the physical world. "The basic commitment is that the fundamental constituents of reality—perhaps electrons and quarks—have incredibly simple forms of experience."

References

- David Armstrong (1980). The Nature of Mind and Other Essays. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 0-7022-1528-7.

- Gilbert Ryle (1949). The Concept of Mind. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73295-9.