Camp Westerbork, also known as Westerbork transit camp, was a Nazi transit camp in the province of Drenthe in the Northeastern Netherlands, during World War II. It was located in the municipality of Westerbork, current-day Midden-Drenthe. Camp Westerbork was used as a staging location for sending Jews, Sinti and Roma to concentration camps elsewhere.

Westerbork is a village in the municipality of Midden-Drenthe in the Netherlands. It is located in the middle of the eastern province of Drenthe. During World War II, the Westerbork transit camp was located near the village. The Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope and the Camp Westerbork Museum are now situated at the site.

The history of the Jews in the Netherlands largely dates to the late 16th century and 17th century, when Sephardic Jews from Portugal and Spain began to settle in Amsterdam and a few other Dutch cities, because the Netherlands was an unusual center of religious tolerance. Since Portuguese Jews had not lived under rabbinic authority for decades, the first generation of those embracing their ancestral religion had to be formally instructed in Jewish belief and practice. This contrasts with Ashkenazi Jews from central Europe, who, although persecuted, lived in organized communities. Seventeenth-century Amsterdam was referred to as the "Dutch Jerusalem" for its importance as a center of Jewish life. In the mid 17th century, Ashkenazi Jews from central and eastern Europe migrated. Both groups migrated for reasons of religious liberty, to escape persecution, now able to live openly as Jews in separate organized, autonomous Jewish communities under rabbinic authority. They were also drawn by the economic opportunities in the Netherlands, a major hub in world trade.

Ellen Burka was a Canadian-Dutch figure skater and coach. She became a member of the Order of Canada in 1978 and was inducted into Canada's Sports Hall of Fame in 1996.

Herzogenbusch was a Nazi concentration camp located in Vught near the city of 's-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands. The camp was opened in 1943 and held 31,000 prisoners. 749 prisoners died in the camp, and the others were transferred to other camps shortly before Herzogenbusch was liberated by the Allied Forces in 1944. After the war, the camp was used as a prison for Germans and for Dutch collaborators. Today there is a visitors' center which includes exhibitions and a memorial remembering the camp and its victims.

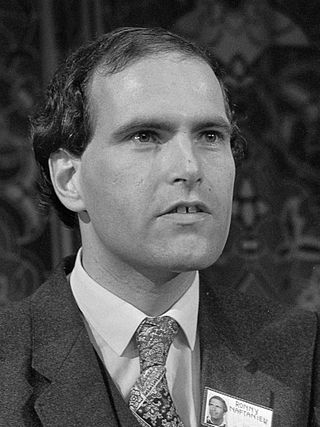

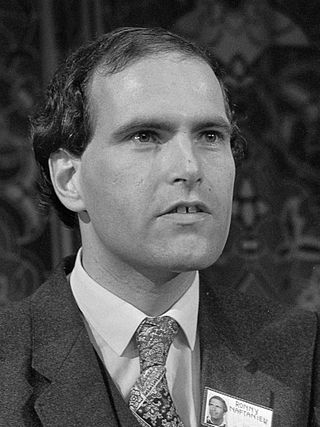

Ronald Maurice (Ronny) Naftaniel is the former director of the Center for Information and Documentation Israel (CIDI), in The Hague, The Netherlands, having served in this role from 1980 to 2013.

Marianne "Janny" Brandes-Brilleslijper was a Dutch Holocaust survivor and one of the last people to see Anne Frank. She is the sister of singer Lin Jaldati. Both Brandes-Brilleslijper and Jaldati were in the Westerbork, Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps with Anne and her older sister Margot Frank.

Selma Engel-Wijnberg was one of only two Dutch Jewish Holocaust survivors of the Sobibor extermination camp. She escaped during the 1943 uprising, hid in Poland, and survived the war. Engel-Wijnberg immigrated to the United States from Israel with her family in 1957, settling in Branford, Connecticut. She returned to Europe again only to testify against the war criminals of Sobibor. In 2010 she was in the Netherlands to receive the governmental honour of Knight in the Order of Oranje-Nassau.

Johan Willem van Hulst was a Dutch school director, university professor, author, politician, chess player and centenarian. In 1943, with the help of the Dutch resistance and students of the nearby University of Amsterdam, he was instrumental in saving over 600 Jewish children from the nursery of the Hollandsche Schouwburg who were destined for deportation to Nazi concentration camps. For his humanitarian actions he received the Yad Vashem distinction Righteous Among the Nations from the State of Israel in 1973.

Martinus (Tinus) Tels was a Dutch physicist and chemical engineer. He was a professor of chemical engineering, dean of the department of chemical engineering and the ninth rector magnificus of the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Bloeme Evers-Emden was a Dutch lecturer and child psychologist who extensively researched the phenomenon of "hidden children" during World War II and wrote four books on the subject in the 1990s. Her interest in the topic grew out of her own experiences during World War II, when she was forced to go into hiding from the Nazis and was subsequently arrested and deported to Auschwitz on the last transport leaving the Westerbork transit camp on 3 September 1944. Together with her on the train were Anne Frank and her family, whom she had known in Amsterdam. She was liberated on 8 May 1945.

Jules Schelvis was a Dutch Jewish historian, writer, printer, and Holocaust survivor. Schelvis was the sole survivor among the 3,005 people on the 14th transport from Westerbork to Sobibor extermination camp, having been selected to work at nearby Dorohucza labour camp. He is known for his memoirs and historical research about Sobibor, for which he earned an honorary doctorate from the University of Amsterdam, Officier in the Order of Orange-Nassau, and Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland.

Geertruida Wijsmuller-Meijer was a Dutch resistance fighter who brought Jewish children and adults into safety before and during the Second World War. Together with other people involved in the pre-war Kindertransport, she saved the lives of more than 10,000 Jewish children, fleeing anti-Semitism. She was honored as Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem. After the war she served on the Amsterdam city council.

Lippmann, Rosenthal & Co. or LiroBank originally a Dutch Jewish bank, was seized and used by Nazis for looting Jewish property during the German occupation of the Netherlands during World War II.

The Holocaust in the Netherlands was organized by Nazi Germany in occupied Netherlands as part of the Holocaust across Europe during the Second World War. The Nazi occupation in 1940 immediately began disrupting the norms of Dutch society, separating Dutch Jews in multiple ways from the general Dutch population. The Nazis used existing Dutch civil administration as well as the Dutch Jewish Council "as an invaluable means to their end".

The Committee for Jewish Refugees was a Dutch charitable organization that operated from 1933 to 1941. At first, it managed the thousands of Jewish refugees who were fleeing the Nazi regime in Germany. These refugees were crossing the border from Germany into the Netherlands. The committee largely decided which of the refugees could remain in the Netherlands. The others generally returned to Germany. For the refugees permitted to stay, it provided support in several ways. These included direct financial aid and assistance with employment and with further emigration.

Henriëtte Henriquez Pimentel was a Dutch teacher and trained nurse who during the Second World War headed a crèche in Amsterdam which cared for small children while their parents were otherwise occupied. Together with Walter Süskind and Johan van Hulst, from around October 1942 she helped to save the lives of hundreds of Jewish infants by smuggling them into the homes of sympathetic host families. After being arrested by the Nazis in April 1943, she was murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp the following September.

Max Windmüller was a German member of the Dutch resistance. He was forced to flee from the National Socialists to the Netherlands with his parents because of their Jewish faith. He joined the Westerweel Group there and saved the lives of many Jewish children and young people. The members of the Westerweel group organized identification papers, hiding places and escape opportunities, especially for German-Jewish children and young people who had fled from Germany. In this group, Jews and members of other faiths worked together to save the Jews from persecution. Such cooperation was not a matter of course in the Netherlands. Windmüller personally saved around 100 young Jews, and the entire Westerweel group saved 393 Jews. In July 1944, the Gestapo stormed a secret meeting of the Resistance group in Paris in which Windmüller and other members of the Jewish resistance were arrested. They were then taken to Gestapo headquarters where they were interrogated and tortured. When the liberation of the camp by Allied troops was imminent, Windmüller was deported from occupied France with the last transport. On 21 April 1945, he was shot by a Schutzstaffel member.

Camp Barneveld was an internment camp consisting of two buildings for Dutch Jews near the town of Barneveld, the Netherlands during the German occupation in World War II. Dutch civil servant Karel Frederiks had made an arrangement, later called Plan Frederiks, with the occupiers to keep a small group of Dutch Jews in the Netherlands and exclude them from deportation to the labour, concentration, or extermination camps abroad. At first, in December 1942, a castle called De Schaffelaar was used to house the interned Jews. When De Schaffelaar was full, a nearby large villa called De Biezen and its barracks were added. Although the Nazis did eventually, in September 1943, deport the group of around 650 Jews from Camp Barneveld to Westerbork transit camp and then on to concentration camp Theresienstadt in Bohemia, almost all survived.

The National Holocaust Names Memorial (Amsterdam) (Dutch: Holocaust Namenmonument) is since 2021 the Dutch national memorial for the Holocaust and the Porajmos at Amsterdam. It commemorates the approximately 102,000 Jewish victims from the Netherlands who were arrested by the Nazi regime during the German occupation of the country (1940-1945), deported and mostly murdered in the Auschwitz and Sobibor death camps, as well as 220 Roma and Sinti victims.