Education reform is the name given to the goal of changing public education. The meaning and education methods have changed through debates over what content or experiences result in an educated individual or an educated society. Historically, the motivations for reform have not reflected the current needs of society. A consistent theme of reform includes the idea that large systematic changes to educational standards will produce social returns in citizens' health, wealth, and well-being.

Progressive education, or educational progressivism, is a pedagogical movement that began in the late 19th century and has persisted in various forms to the present. In Europe, progressive education took the form of the New Education Movement. The term progressive was engaged to distinguish this education from the traditional curricula of the 19th century, which was rooted in classical preparation for the early-industrial university and strongly differentiated by social class. By contrast, progressive education finds its roots in modern, post-industrial experience. Most progressive education programs have these qualities in common:

Educational psychology is the branch of psychology concerned with the scientific study of human learning. The study of learning processes, from both cognitive and behavioral perspectives, allows researchers to understand individual differences in intelligence, cognitive development, affect, motivation, self-regulation, and self-concept, as well as their role in learning. The field of educational psychology relies heavily on quantitative methods, including testing and measurement, to enhance educational activities related to instructional design, classroom management, and assessment, which serve to facilitate learning processes in various educational settings across the lifespan.

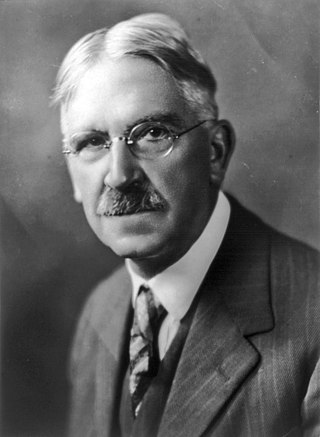

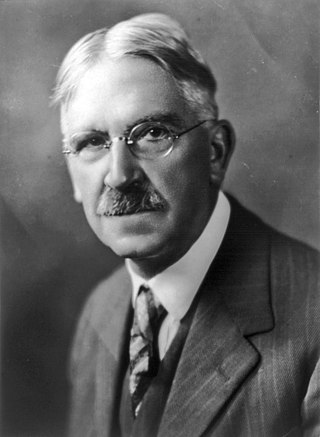

John Dewey was an American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer. He was one of the most prominent American scholars in the first half of the twentieth century.

The philosophy of education is the branch of applied philosophy that investigates the nature of education as well as its aims and problems. It also examines the concepts and presuppositions of education theories. It is an interdisciplinary field that draws inspiration from various disciplines both within and outside philosophy, like ethics, political philosophy, psychology, and sociology. Many of its theories focus specifically on education in schools but it also encompasses other forms of education. Its theories are often divided into descriptive theories, which provide a value-neutral description of what education is, and normative theories, which investigate how education should be practiced.

"My Pedagogic Creed" is an article written by John Dewey and published in School Journal in 1897. The article is broken into five sections, with each paragraph beginning "I believe." It has been referenced over 4100 times, and continues to be referenced, as a testament to the lasting impact of the article's ideas.

Pedagogy, from Ancient Greek παιδαγωγία (paidagōgía), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken as an academic discipline, is the study of how knowledge and skills are imparted in an educational context, and it considers the interactions that take place during learning. Both the theory and practice of pedagogy vary greatly as they reflect different social, political, and cultural contexts.

Early childhood education (ECE), also known as nursery education, is a branch of education theory that relates to the teaching of children from birth up to the age of eight. Traditionally, this is up to the equivalent of third grade. ECE is described as an important period in child development.

Experiential education is a philosophy of education that describes the process that occurs between a teacher and student that infuses direct experience with the learning environment and content. The term is not interchangeable with experiential learning; however experiential learning is a sub-field and operates under the methodologies of experiential education. The Association for Experiential Education regards experiential education as "a philosophy that informs many methodologies in which educators purposefully engage with learners in direct experience and focused reflection in order to increase knowledge, develop skills, clarify values, and develop people's capacity to contribute to their communities". Experiential education is the term for the philosophy and educational progressivism is the movement which it informed. The Journal of Experiential Education publishes peer-reviewed empirical and theoretical academic research within the field.

In education, a curriculum is broadly defined as the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experiences in terms of the educator's or school's instructional goals. A curriculum may incorporate the planned interaction of pupils with instructional content, materials, resources, and processes for evaluating the attainment of educational objectives. Curricula are split into several categories: the explicit, the implicit, the excluded, and the extracurricular.

Project-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered pedagogy that involves a dynamic classroom approach in which it is believed that students acquire a deeper knowledge through active exploration of real-world challenges and problems. Students learn about a subject by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to a complex question, challenge, or problem. It is a style of active learning and inquiry-based learning. PBL contrasts with paper-based, rote memorization, or teacher-led instruction that presents established facts or portrays a smooth path to knowledge by instead posing questions, problems, or scenarios.

This is an index of education articles.

Democratic education is a type of formal education that is organized democratically, so that students can manage their own learning and participate in the governance of their school. Democratic education is often specifically emancipatory, with the students' voices being equal to the teacher's.

Curriculum theory (CT) is an academic discipline devoted to examining and shaping educational curricula. There are many interpretations of CT, being as narrow as the dynamics of the learning process of one child in a classroom to the lifelong learning path an individual takes. CT can be approached from the educational, philosophical, psychological and sociological perspectives. James MacDonald states "one central concern of theorists is identifying the fundamental unit of curriculum with which to build conceptual systems. Whether this be rational decisions, action processes, language patterns, or any other potential unit has not been agreed upon by the theorists." Curriculum theory is fundamentally concerned with values, the historical analysis of curriculum, ways of viewing current educational curriculum and policy decisions, and theorizing about the curricula of the future.

The Avery Coonley School (ACS), commonly called Avery Coonley, is an independent, coeducational day school serving academically gifted students in preschool through eighth grade (approximately ages 3 to 14), and is located in Downers Grove, DuPage County, Illinois. The school was founded in 1906 to promote the progressive educational theories developed by John Dewey and other turn-of-the-20th-century philosophers, and was a nationally recognized model for progressive education well into the 1940s. From 1943 to 1965, Avery Coonley was part of the National College of Education (now National Louis University), serving as a living laboratory for teacher training and educational research. In the 1960s, ACS became a regional research center and a leadership hub for independent schools, and began to focus on the education of the gifted.

Education sciences, also known as education studies, education theory, and traditionally called pedagogy, seek to describe, understand, and prescribe education policy and practice. Education sciences include many topics, such as pedagogy, andragogy, curriculum, learning, and education policy, organization and leadership. Educational thought is informed by many disciplines, such as history, philosophy, sociology, and psychology.

Eleanor Ruth Duckworth is a teacher, teacher educator, and psychologist.

Learning by doing is a theory that places heavy emphasis on student engagement and is a hands-on, task-oriented, process to education. The theory refers to the process in which students actively participate in more practical and imaginative ways of learning. This process distinguishes itself from other learning approaches as it provides many pedagogical advantages to more traditional learning styles, such those which privilege inert knowledge. Learning-by-doing is related to other types of learning such as adventure learning, action learning, cooperative learning, experiential learning, peer learning, service-learning, and situated learning.

Individual education is a school system rooted in the individual psychology of Alfred Adler. Designed by Raymond Corsini, the individual education program includes a number of basic principles. The program consists of three components academic, creative/applied and socialization. Corsini also outlined disciplinary procedures and a number of other principles to ensure the most productive possible school environment.

Educational management refers to the administration of the education system in which a group combines human and material resources to supervise, plan, strategise, and implement structures to execute an education system. Education is the equipping of knowledge, skills, values, beliefs, habits, and attitudes with learning experiences. The education system is an ecosystem of professionals in educational institutions, such as government ministries, unions, statutory boards, agencies, and schools. The education system consists of political heads, principals, teaching staff, non-teaching staff, administrative personnel and other educational professionals working together to enrich and enhance. At all levels of the educational ecosystem, management is required; management involves the planning, organising, implementation, review, evaluation, and integration of an institution.