Related Research Articles

Yoshiwara (吉原) was a famous yūkaku in Edo, present-day Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1617, Yoshiwara was one of three licensed and well-known red-light districts created during the early 17th century by the Tokugawa shogunate, alongside Shimabara in Kyoto in 1640 and Shinmachi in Osaka.

Chikamatsu Monzaemon was a Japanese dramatist of jōruri, the form of puppet theater that later came to be known as bunraku, and the live-actor drama, kabuki. The Encyclopædia Britannica has written that he is "widely regarded as the greatest Japanese dramatist". His most famous plays deal with double-suicides of honor bound lovers. Of his puppet plays, around 70 are jidaimono (時代物) and 24 are sewamono (世話物). The domestic plays are today considered the core of his artistic achievement, particularly works such as The Courier for Hell (1711) and The Love Suicides at Amijima (1721). His histories are viewed less positively, though The Battles of Coxinga (1715) remains praised.

Brooke Allison English is a fictional character on the television soap opera All My Children. Originated by Elissa Leeds in 1976, she was portrayed by Julia Barr from June 1976 to June 1981 and from November 1982 to December 20, 2006. Harriet Hall played the role from June 1981 through March 1982. Barr made a special appearance as Brooke on January 5, 2010, as part of the series' 40th anniversary, and returned on February 23, 2010, for a two-month stint until April 23, 2010. She later returned for the show's final week on ABC on September 16, 2011. She returned as Brooke on the Prospect Park's continuation of All My Children.

In Japanese traditional beliefs and literature, onryō are a type of ghost believed to be capable of causing harm in the world of the living, injuring or killing enemies, or even causing natural disasters to exact vengeance to "redress" the wrongs it received while alive, then taking their spirits from their dying bodies. Onryō are often depicted as wronged women, who are traumatized by what happened during life and exact revenge in death.

Star Ocean: The Second Story is a seven volume manga series written and illustrated by Mayumi Azuma. Based on the tri-Ace role-playing video game Star Ocean: The Second Story, it follows the exploits of Claude C. Kenny, a young ensign in the Earth Federation who finds himself stranded on the Planet Expel. He meets Rena Lanford, a young girl living in the village of Arlia who declares that he is the legendary warrior their legends speak of who will save their troubled world from disaster. The series was serialized in Monthly Shōnen Gangan from 1998 to 1999.

Double Suicide is a 1969 film directed by Masahiro Shinoda. It is based on the 1721 play The Love Suicides at Amijima by Monzaemon Chikamatsu. This play is often performed with puppets. In the film, the story is performed with live actors but makes use of Japanese theatrical traditions such as the kuroko who invisibly interact with the actors, and the set is non-realist. The kuroko prepare for a modern-day presentation of a puppet play while a voice-over, presumably the director, calls on the telephone to find a location for the penultimate scene of the lovers' suicide. Soon, human actors substitute for the puppets, and the action proceeds in a naturalistic fashion, until from time to time the kuroko intervene to accomplish scene shifts or heighten the dramatic intensity of the two lovers' resolve to be united in death.

Banchō Sarayashiki is a Japanese ghost story (kaidan) of broken trust and broken promises, leading to a dismal fate. Alternatively referred to as the sarayashiki tradition, all versions of the tale revolve around a servant, who dies unjustly and returns to haunt the living. Some versions take place in Harima Province or Banshū (播州), others in the Banchō (番町) area in Edo.

Santō Kyōden was a Japanese artist, writer, and the owner of a tobacco shop during the Edo period. His real name was Iwase Samuru , and he was also known popularly as Kyōya Denzō . He began his professional career illustrating the works of others before writing his own Kibyōshi and Sharebon. Within his works, Kyōden often included references to his shop to increase sales. Kyōden's works were affected by the shifting publication laws of the Kansei Reforms which aimed to punish writers and their publishers for writings related to the Yoshiwara and other things that were deemed to be "harmful to society" at the time by the Tokugawa Bakufu. As a result of his punishment in 1791, Kyōden shifted his writings to the more didactic Yomihon. During the 1790s, Santō Kyōden became a household name and one of his works could sell as many as 10,000 copies, numbers that were previously unheard of for the time.

The Battles of Coxinga is a puppet play by Chikamatsu Monzaemon. It was his most popular play. First staged on November 26, 1715, in Osaka, it ran for the next 17 months, far longer than the usual few weeks or months. Its enduring popularity can largely be attributed to its effectiveness as entertainment. Its many scenes over more than seven years follow the adventures of Coxinga in restoring the rightful dynasty of China. It features effects uniquely suited for the puppet theater, such as the villain Ri Tōten gouging out an eye. Donald Keene suggests that the adventures in exotic China played well in isolationist Tokugawa Japan. While generally not considered as great in literary quality as some of Chikamatsu's domestic tragedies like The Love Suicides at Amijima, it is generally agreed to be his best historical play.

The Love Suicides at Sonezaki is a jōruri play by the Japanese playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon. The double suicides that occurred on May 22, 1703 inspired Chikamatsu to write this play and thus The Love Suicides at Sonezaki made its debut performance on June 20, 1703. Chikamatsu added new scenes in the 1717 revival including the villain's punishment. The Love Suicides at Sonezaki's reception was popular and helped springboard Chikamatsu's future success as a playwright. In the first year alone since the play's premirere, no less than seventeen couples committed double suicide. In fact, the bakufu banned Chikamatsu's shinjū plays in 1722 because of their content's popularity. The Love Suicides at Sonezaki was Chikamatsu's first "domestic tragedy" or "domestic play" (sewamono) and his first love-suicide play (shinjūmono). Until this play, the common topic for jōruri was jidaimono or "history plays" while kabuki performances showed domestic plays. The Love Suicides at Sonezaki separates into three scenes, staged over a day and a night. The two central characters are an orphaned oil clerk named Tokubei and Ohatsu, the courtesan he loves. There is a beginning scene that shows Ohatsu going on a pilgrimage that performances and translations often leave out. This play also includes a religious aspect involving Confucianism and Buddhism.

The Nakasu was a short-lived, but vibrant and popular entertainment district in Edo, Japan. It was built upon an artificial landfill in the Sumida River, at a place called Mitsumata, in 1771, and lasted until 1790, when the landfill was removed.

Takao II, also known as Sendai Takao or Manji Takao, was a tayū of the Yoshiwara red light district of Edo, and one of the most famous courtesans of Japan's Edo period (1603–1867). She debuted in 1655 as the leading courtesan of the Great Miura, the most prestigious Yoshiwara brothel of the day, and rapidly became the leading courtesan of the entirety of Yoshiwara.

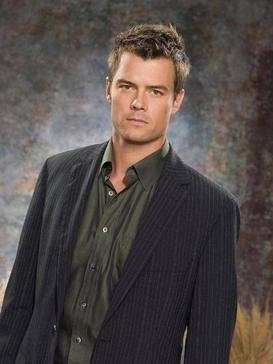

Leonardo "Leo" du Pres is a fictional character from the American ABC Daytime soap opera All My Children. The role was portrayed by actor Josh Duhamel from November 22, 1999, to the character's death onscreen on October 17, 2002. Duhamel reprised his role on December 24, 2003, and for two episodes in August 2011.

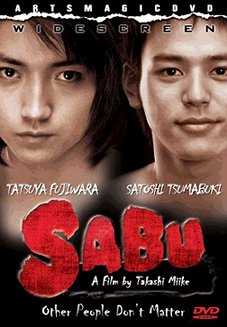

Sabu is a 2002 Japanese jidaigeki film directed by Takashi Miike and adapted from the classic Japanese rite-of-passage novel by Shūgorō Yamamoto.

The Courier for Hell or Courier of Hell is a love-suicide play by the Japanese writer Chikamatsu Monzaemon, written in 1711. It follows a similar storyline to some of his other love-suicide plays, including The Love Suicides at Sonezaki and The Love Suicides at Amijima. The Courier for Hell was based on real events that took place in Osaka in 1710. It is one of the most celebrated of his domestic plays.

Three for the Road is a 2007 Japanese film directed by Hideyuki Hirayama.

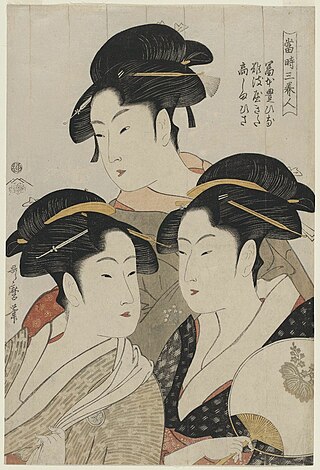

Three Beauties of the Present Day is a nishiki-e colour woodblock print from c. 1792–93 by Japanese ukiyo-e artist Kitagawa Utamaro. The triangular composition depicts the profiles of three celebrity beauties of the time: geisha Tomimoto Toyohina, and teahouse waitresses Naniwaya Kita and Takashima Hisa. The print is also known under the titles Three Beauties of the Kansei Era and Three Famous Beauties.

The Woman-Killer and the Hell of Oil is a Bunraku play by Chikamatsu Monzaemon, also performed in kabuki.

Night Druma.k.a.The Adulteress is a 1958 Japanese historical drama film directed by Tadashi Imai. It was written by Kaneto Shindo and Shinobu Hashimoto, based on the 1706 play Horikawa nami no tsuzumi by Monzaemon Chikamatsu. Film historians regard Night Drum as one of director Imai's major works.

One Hundred Ghost Stories is a series of ukiyo-e woodblock prints made by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) in the Yūrei-zu genre circa 1830. He created this series around the same time he was creating his most famous works, the Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series. There are only five prints in this series, though as its title suggests, the publisher, Tsuruya Kiemon, and Hokusai wanted to make a series of one hundred prints. Hokusai was in his seventies when he worked on this series, and though his most famous impressions are landscape and wild-life works, he was attune to the superstitions of the Edo period. This culminated in him creating these yokai prints of popular ghost stories being told at the time. The prints show scenes from such stories, that could be recited during the game of Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai.

References

- pgs. 133–169 of Four Major Plays of Chikamatsu