The Tao or Dao is the natural way of the universe, primarily as conceived in East Asian philosophy and religion. This seeing of life cannot be grasped as a concept. Rather, it is seen through actual living experience of one's everyday being. The concept is represented by the Chinese character 道, which has meanings including 'way', 'path', 'road', and sometimes 'doctrine' or 'principle'.

Eastern philosophy includes the various philosophies that originated in East and South Asia, including Chinese philosophy, Japanese philosophy, Korean philosophy, and Vietnamese philosophy, which are dominant in East Asia; and Indian philosophy, which are dominant in South Asia, Southeast Asia, Tibet, Japan and Mongolia.

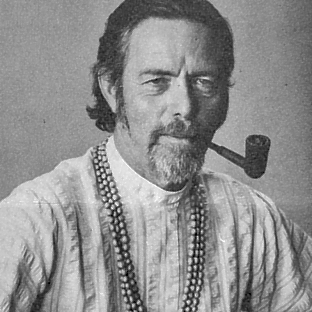

Alan Wilson Watts was a British and American writer, speaker, and self-styled "philosophical entertainer", known for interpreting and popularising Buddhist, Taoist, and Hindu philosophy for a Western audience.

Satori is a Japanese Buddhist term for "awakening", "comprehension; understanding". The word derives from the Japanese verb satoru.

Buddhism in the West broadly encompasses the knowledge and practice of Buddhism outside of Asia, in the Western world. Occasional intersections between Western civilization and the Buddhist world have been occurring for thousands of years. Greek colonies existed in India during the Buddha's life, as early as the 6th century. The first Westerners to become Buddhists were Greeks who settled in Bactria and India during the Hellenistic period. They became influential figures during the reigns of the Indo-Greek kings, whose patronage of Buddhism led to the emergence of Greco-Buddhism and Greco-Buddhist art.

The Kyoto School is the name given to the Japanese philosophical movement centered at Kyoto University that assimilated Western philosophy and religious ideas and used them to reformulate religious and moral insights unique to the East Asian philosophical tradition. However, it is also used to describe postwar scholars who have taught at the same university, been influenced by the foundational thinkers of Kyoto school philosophy, and who have developed distinctive theories of Japanese uniqueness. To disambiguate the term, therefore, thinkers and writers covered by this second sense appear under The Kyoto University Research Centre for the Cultural Sciences.

Nondualism includes a number of philosophical and spiritual traditions that emphasize the absence of fundamental duality or separation in existence. This viewpoint questions the boundaries conventionally imposed between self and other, mind and body, observer and observed, and other dichotomies that shape our perception of reality. As a field of study, nondualism delves into the concept of nonduality and the state of nondual awareness, encompassing a diverse array of interpretations, not limited to a particular cultural or religious context; instead, nondualism emerges as a central teaching across various belief systems, inviting individuals to examine reality beyond the confines of dualistic thinking.

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki, self-rendered in 1894 as "Daisetz", was a Japanese essayist, philosopher, religious scholar, and translator. He was an authority on Buddhism, especially Zen and Shin, and was instrumental in spreading interest in these to the West. He was also a prolific translator of Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese and Sanskrit literature. Suzuki spent several lengthy stretches teaching or lecturing at Western universities and devoted many years to a professorship at Ōtani University, a Japanese Buddhist school.

Travers Christmas Humphreys, QC was a British jurist who prosecuted several controversial cases in the 1940s and 1950s, and who later became a judge at the Old Bailey. He also wrote a number of works on Mahayana Buddhism and in his day was the best-known British convert to Buddhism. In 1924 he founded what became the London Buddhist Society, which was to have a seminal influence on the growth of the Buddhist tradition in Britain. His former home in St John's Wood, London, is now a Buddhist temple. He was an enthusiastic proponent of the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship.

Reginald Horace Blyth was an English writer and devotee of Japanese culture. He is most famous for his writings on Zen and on haiku poetry.

Japanese Zen refers to the Japanese forms of Zen Buddhism, an originally Chinese Mahāyāna school of Buddhism that strongly emphasizes dhyāna, the meditative training of awareness and equanimity. This practice, according to Zen proponents, gives insight into one's true nature, or the emptiness of inherent existence, which opens the way to a liberated way of living.

Sokei-an Shigetsu Sasaki, born Yeita Sasaki, was a Japanese Rinzai monk who founded the Buddhist Society of America in New York City in 1930. Influential in the growth of Zen Buddhism in the United States, Sokei-an was one of the first Japanese masters to live and teach in America and the foremost purveyor in the U.S. of Direct Transmission. In 1944 he married American Ruth Fuller Everett. He died in May 1945 without leaving behind a Dharma heir. One of his better known students was Alan Watts, who studied under him briefly. Watts was a student of Sokei-an in the late 1930s.

Buddhism includes an analysis of human psychology, emotion, cognition, behavior and motivation along with therapeutic practices. Buddhist psychology is embedded within the greater Buddhist ethical and philosophical system, and its psychological terminology is colored by ethical overtones. Buddhist psychology has two therapeutic goals: the healthy and virtuous life of a householder and the ultimate goal of nirvana, the total cessation of dissatisfaction and suffering (dukkha).

Buddhist modernism are new movements based on modern era reinterpretations of Buddhism. David McMahan states that modernism in Buddhism is similar to those found in other religions. The sources of influences have variously been an engagement of Buddhist communities and teachers with the new cultures and methodologies such as "Western monotheism; rationalism and scientific naturalism; and Romantic expressivism". The influence of monotheism has been the internalization of Buddhist gods to make it acceptable in modern Western society, while scientific naturalism and romanticism has influenced the emphasis on current life, empirical defense, reason, psychological and health benefits.

Zen is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that originated in China during the Tang dynasty as the Chan School or the Buddha-mind school, and later developed into various sub-schools and branches. Zen was influenced by Taoism, especially Neo-Daoist thought, and developed as a distinguished school of Chinese Buddhism. From China, Chán spread south to Vietnam and became Vietnamese Thiền, northeast to Korea to become Seon Buddhism, and east to Japan, becoming Japanese Zen.

Secular Buddhism—sometimes also referred to as agnostic Buddhism, Buddhist agnosticism, ignostic Buddhism, atheistic Buddhism, pragmatic Buddhism, Buddhist atheism, or Buddhist secularism—is a broad term for a form of Buddhism based on humanist, skeptical, and agnostic values, valuing pragmatism and (often) naturalism, eschewing beliefs in the supernatural or paranormal. It can be described as the embrace of Buddhist rituals and philosophy for their secular benefits by people who are atheist or agnostic.

Modern scientific research on the history of Zen discerns three main narratives concerning Zen, its history and its teachings: Traditional Zen Narrative (TZN), Buddhist Modernism (BM), Historical and Cultural Criticism (HCC). An external narrative is Nondualism, which claims Zen to be a token of a universal nondualist essence of religions.

Buddhist thought and Western philosophy include several parallels.

Alan Watts was an orator and philosopher of the 20th century. He spent time reflecting on personal identity and higher consciousness. According to the critic Erik Davis, his "writings and recorded talks still shimmer with a profound and galvanising lucidity." These works are not accessible in the same way as his many books.

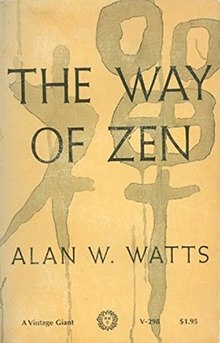

The Zen boom was a rise in interest in Zen practices in North America, Europe, and elsewhere around the world beginning in the 1950s and continuing into the 1970s. Zen was seen as an alluring philosophical practice that acted as a tranquilizing agent against the memory of World War II, active Cold War conflicts, nuclear anxieties, and other social injustices. The surge in interest is thought to have been heavily influenced by lectures on Zen given by D.T. Suzuki at Columbia University from 1950 to 1958, as well as his many books on the subject. Authors like Ruth Fuller Sasaki and Gary Snyder also traveled to Japan to formally study Zen Buddhism. Snyder would influence fellow Beat poets from Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac, to Philip Whalen, to also follow his interest in Zen. Alan Watts also published his classic book The Way of Zen as a guide to Zen intended for western audiences.