This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic.(March 2025) |

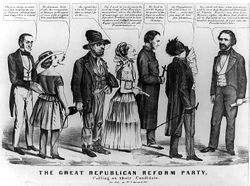

The twin relics of barbarism refer to the popular nineteenth-century phrase that linked the practices of slavery and polygamy in the United States. Attention to these twin relics increased following the 1856 Republican National Convention as the party acknowledged both practices in their party platform. Within the party's planks, they called on Congress to firmly denounce the "twin relics of barbarism – Polygamy and Slavery." [1] During this period, slavery was widely practiced among southern states, and polygamy was becoming prevalent among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (popularly referred to as Mormons). The growth of these practices stoked fear and uncertainty in the nation at large as the two practices were seen as "incongruous with the pure and the free, the just and safe principles inaugurated by the [American] Revolution." [2] As a result of the widespread opposition to each, they were increasingly coupled together in national print media throughout the country.

Contents

- 1856 Republican National Convention

- The first Republican National Convention

- Opposition to slavery

- Opposition to polygamy

- Linking the twin relics

- Initial connection

- Effects of the media

- Refuting the connection

- The downfall of the twin relics

- Legislation to end slavery

- Legislation to end polygamy

- References

Following the Civil War, slavery was abolished and legal equality for African-Americans began with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, [3] the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, although penal labor remains legal in the United States as a punishment for a crime.

Polygamy was eventually outlawed in the 1880s following the passage of numerous pieces of anti-polygamy legislation including the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862, the Edmunds Act of 1882, and the Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887 as well as the landmark Supreme Court case Reynolds v. United States.

Legal efforts to eradicate polygamy persisted into the 20th and 21st centuries. These efforts, such as the 1953 Short Creek Raid conducted by the state of Arizona, clandestine surveillance of suspected polygamists throughout the 1900s by Utahan law enforcement, [4] and Brown v Buhman [5] in 2016 have proved to be unpopular and ineffective.