In mathematics, a geometric algebra is an extension of elementary algebra to work with geometrical objects such as vectors. Geometric algebra is built out of two fundamental operations, addition and the geometric product. Multiplication of vectors results in higher-dimensional objects called multivectors. Compared to other formalisms for manipulating geometric objects, geometric algebra is noteworthy for supporting vector division and addition of objects of different dimensions.

In Euclidean geometry, an affine transformation or affinity is a geometric transformation that preserves lines and parallelism, but not necessarily Euclidean distances and angles.

In Euclidean geometry, two objects are similar if they have the same shape, or if one has the same shape as the mirror image of the other. More precisely, one can be obtained from the other by uniformly scaling, possibly with additional translation, rotation and reflection. This means that either object can be rescaled, repositioned, and reflected, so as to coincide precisely with the other object. If two objects are similar, each is congruent to the result of a particular uniform scaling of the other.

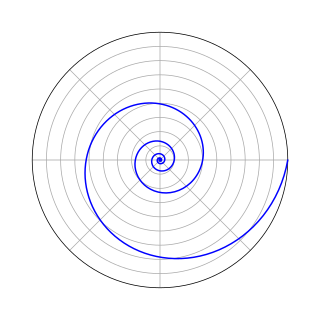

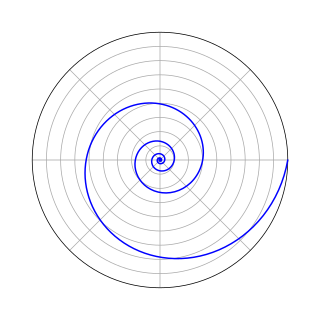

A logarithmic spiral, equiangular spiral, or growth spiral is a self-similar spiral curve that often appears in nature. The first to describe a logarithmic spiral was Albrecht Dürer (1525) who called it an "eternal line". More than a century later, the curve was discussed by Descartes (1638), and later extensively investigated by Jacob Bernoulli, who called it Spira mirabilis, "the marvelous spiral".

Kinematics is a subfield of physics, developed in classical mechanics, that describes the motion of points, bodies (objects), and systems of bodies without considering the forces that cause them to move. Kinematics, as a field of study, is often referred to as the "geometry of motion" and is occasionally seen as a branch of mathematics. A kinematics problem begins by describing the geometry of the system and declaring the initial conditions of any known values of position, velocity and/or acceleration of points within the system. Then, using arguments from geometry, the position, velocity and acceleration of any unknown parts of the system can be determined. The study of how forces act on bodies falls within kinetics, not kinematics. For further details, see analytical dynamics.

Conduction is the process by which heat is transferred from the hotter end to the colder end of an object. The ability of the object to conduct heat is known as its thermal conductivity, and is denoted k.

In mathematics and physics, the heat equation is a certain partial differential equation. Solutions of the heat equation are sometimes known as caloric functions. The theory of the heat equation was first developed by Joseph Fourier in 1822 for the purpose of modeling how a quantity such as heat diffuses through a given region.

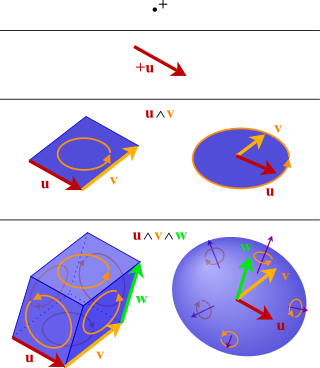

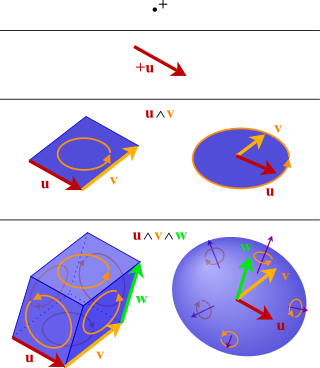

In mathematics, the exterior algebra, or Grassmann algebra, named after Hermann Grassmann, is an algebra that uses the exterior product or wedge product as its multiplication. In mathematics, the exterior product or wedge product of vectors is an algebraic construction used in geometry to study areas, volumes, and their higher-dimensional analogues. The exterior product of two vectors and , denoted by is called a bivector and lives in a space called the exterior square, a vector space that is distinct from the original space of vectors. The magnitude of can be interpreted as the area of the parallelogram with sides and which in three dimensions can also be computed using the cross product of the two vectors. More generally, all parallel plane surfaces with the same orientation and area have the same bivector as a measure of their oriented area. Like the cross product, the exterior product is anticommutative, meaning that for all vectors and but, unlike the cross product, the exterior product is associative.

In mathematics and physics, n-dimensional anti-de Sitter space (AdSn) is a maximally symmetric Lorentzian manifold with constant negative scalar curvature. Anti-de Sitter space and de Sitter space are named after Willem de Sitter (1872–1934), professor of astronomy at Leiden University and director of the Leiden Observatory. Willem de Sitter and Albert Einstein worked together closely in Leiden in the 1920s on the spacetime structure of the universe.

In mathematics, a linear differential equation is a differential equation that is defined by a linear polynomial in the unknown function and its derivatives, that is an equation of the form

In mathematics, a homothety is a transformation of an affine space determined by a point S called its center and a nonzero number called its ratio, which sends point to a point by the rule

Thermal shock is a phenomenon characterized by a rapid change in temperature that results in a transient mechanical load on an object. The load is caused by the differential expansion of different parts of the object due to the temperature change. This differential expansion can be understood in terms of strain, rather than stress. When the strain exceeds the tensile strength of the material, it can cause cracks to form and eventually lead to structural failure.

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to change its shape, area, volume, and density in response to a change in temperature, usually not including phase transitions.

In mathematics, the resultant of two polynomials is a polynomial expression of their coefficients that is equal to zero if and only if the polynomials have a common root, or, equivalently, a common factor. In some older texts, the resultant is also called the eliminant.

In mathematics and theoretical physics, a supermatrix is a Z2-graded analog of an ordinary matrix. Specifically, a supermatrix is a 2×2 block matrix with entries in a superalgebra. The most important examples are those with entries in a commutative superalgebra or an ordinary field.

In quantum computing, quantum finite automata (QFA) or quantum state machines are a quantum analog of probabilistic automata or a Markov decision process. They provide a mathematical abstraction of real-world quantum computers. Several types of automata may be defined, including measure-once and measure-many automata. Quantum finite automata can also be understood as the quantization of subshifts of finite type, or as a quantization of Markov chains. QFAs are, in turn, special cases of geometric finite automata or topological finite automata.

In the mathematical field of abstract algebra, isotopy is an equivalence relation used to classify the algebraic notion of loop.

Heat transfer physics describes the kinetics of energy storage, transport, and energy transformation by principal energy carriers: phonons, electrons, fluid particles, and photons. Heat is energy stored in temperature-dependent motion of particles including electrons, atomic nuclei, individual atoms, and molecules. Heat is transferred to and from matter by the principal energy carriers. The state of energy stored within matter, or transported by the carriers, is described by a combination of classical and quantum statistical mechanics. The energy is different made (converted) among various carriers. The heat transfer processes are governed by the rates at which various related physical phenomena occur, such as the rate of particle collisions in classical mechanics. These various states and kinetics determine the heat transfer, i.e., the net rate of energy storage or transport. Governing these process from the atomic level to macroscale are the laws of thermodynamics, including conservation of energy.

In statistics, modes of variation are a continuously indexed set of vectors or functions that are centered at a mean and are used to depict the variation in a population or sample. Typically, variation patterns in the data can be decomposed in descending order of eigenvalues with the directions represented by the corresponding eigenvectors or eigenfunctions. Modes of variation provide a visualization of this decomposition and an efficient description of variation around the mean. Both in principal component analysis (PCA) and in functional principal component analysis (FPCA), modes of variation play an important role in visualizing and describing the variation in the data contributed by each eigencomponent. In real-world applications, the eigencomponents and associated modes of variation aid to interpret complex data, especially in exploratory data analysis (EDA).

In thermodynamics, thermal pressure is a measure of the relative pressure change of a fluid or a solid as a response to a temperature change at constant volume. The concept is related to the Pressure-Temperature Law, also known as Amontons's law or Gay-Lussac's law.