Booker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, and orator. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the primary leader in the African-American community and of the contemporary Black elite.

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

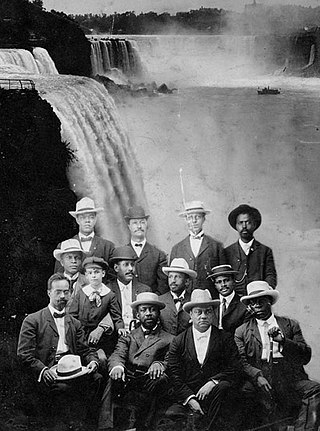

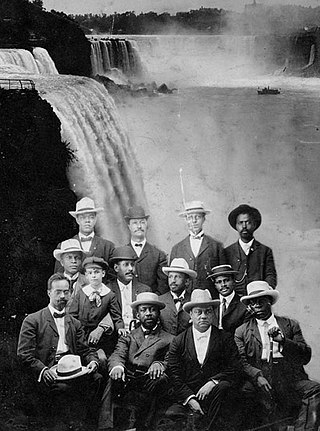

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. It was named for the "mighty current" of change the group wanted to effect and took Niagara Falls as its symbol. The group did not meet in Niagara Falls, New York, but planned its first conference for nearby Buffalo.

Herbert Aptheker was an American Marxist historian and political activist. He wrote more than 50 books, mostly in the fields of African-American history and general U.S. history, most notably, American Negro Slave Revolts (1943), a classic in the field. He also compiled the 7-volume Documentary History of the Negro People (1951–1994). In addition, he compiled a wide variety of primary documents supporting study of African-American history. He was the literary executor for W. E. B. Du Bois.

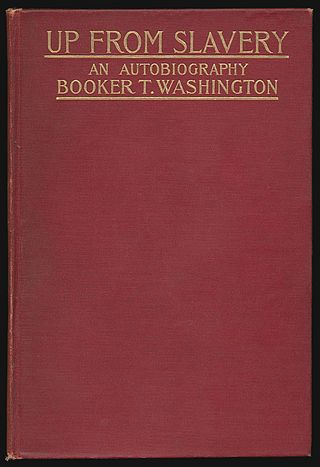

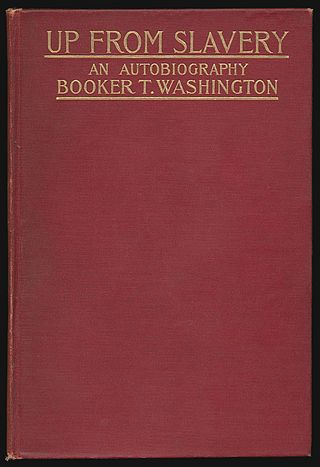

Up from Slavery is the 1901 autobiography of the American educator Booker T. Washington (1856–1915). The book describes his experience of working to rise up from being enslaved as a child during the Civil War, the obstacles he overcame to get an education at the new Hampton Institute, and his work establishing vocational schools like the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to help Black people and other persecuted people of color learn useful, marketable skills and work to pull themselves, as a race, up by the bootstraps. He reflects on the generosity of teachers and philanthropists who helped educate Black and Native Americans. He describes his efforts to instill manners, breeding, health and dignity into students. His educational philosophy stresses combining academic subjects with learning a trade. Washington explained that the integration of practical subjects is partly designed to "reassure the White community of the usefulness of educating Black people".

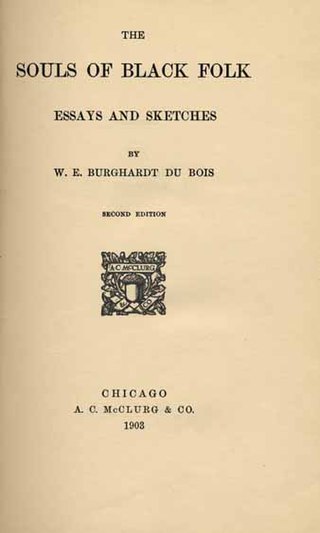

The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches is a 1903 work of American literature by W. E. B. Du Bois. It is a seminal work in the history of sociology and a cornerstone of African-American literature.

The talented tenth is a term that designated a leadership class of African Americans in the early 20th century. Although the term was created by white Northern philanthropists, it is primarily associated with W. E. B. Du Bois, who used it as title of an influential essay, published in 1903. It appeared in The Negro Problem, a collection of essays written by leading African Americans and assembled by Booker T. Washington.

John Gibbs St. Clair Drake was an African-American sociologist and anthropologist whose scholarship and activism led him to document much of the social turmoil of the 1960s, establish some of the first Black Studies programs in American universities, and contribute to the independence movement in Ghana. Drake often wrote about challenges and achievements in race relations as a result of his extensive research.

The Harmon Foundation was established in 1921 by white real-estate developer William E. Harmon (1862–1928). The Foundation originally supported a variety of causes, including playgrounds and nursing programs, but is best known for having funded and collected the work of a large group of African-American artists, many of whom would go on to become widely recognized. After 1947, the foundation expanded its work in the arts to include supporting African and Afro-diasporic artists. The foundation was among the first organizations in the United States to support opportunities for contemporary African-American and African artists to travel between the United States and Africa to study, exhibit their work, and meet other artists. Mary B. Brady was the director of the foundation from 1922 until 1967.

Anson Phelps Stokes was an American educator, historian, clergyman, author, philanthropist and civil rights activist.

Jackson Davis was a principal, education official, and education reformer from Virginia during the Jim Crow era of segregation. He was involved in supervising education programs for African Americans and promoted well maintained manual labor colleges for them. He did not express any opposition to segregation. He took photographs and documented conditions at some of the schools serving African Americans and Native Americans in the southern United States, especially in rural areas. He was also involved with philanthropic organizations, traveled to Africa twice, and was part of a colonization society.

What came to be known as the Atlanta Compromise stemmed from a speech given by Booker T. Washington, president of the Tuskegee Institute, to the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 18, 1895. It was first supported and later opposed by W. E. B. Du Bois and other African-American leaders.

The Phelps Stokes Fund (PS) is a nonprofit fund established in 1911 by the will of New York philanthropist Caroline Phelps Stokes, a member of the Phelps Stokes family. Created as the Trustees of Phelps Stokes Fund, it connects emerging leaders and organizations in Africa and the Americas with resources to help them advance social and economic development.

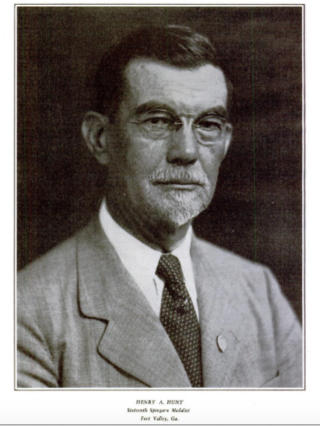

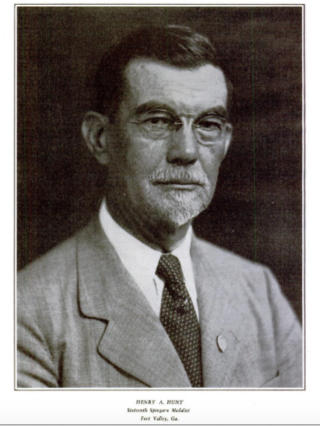

Henry Alexander Hunt was an American educator who led efforts to reach blacks in rural areas of Georgia. He was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), as well as the Harmon Prize. In addition, he was recruited in the 1930s by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to join the president's Black Cabinet, an informal group of more than 40 prominent African Americans appointed to positions in the executive agencies.

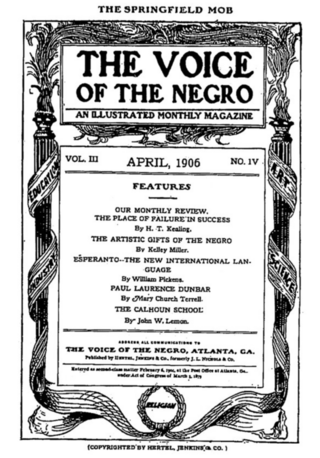

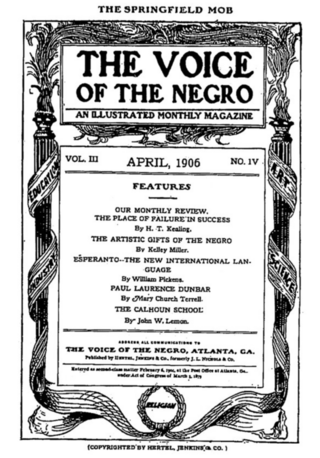

The Voice of the Negro was a literary periodical aimed at a national audience of African Americans which was published from 1904 to 1907. It was created in Atlanta, Georgia in June 1904 by Austin N. Jenkins, the white manager of the publishing company J. L. Nichols and Company. He gave full control of the magazine to the Black editors John W. E. Bowen, Sr. and Jesse Max Barber.

The Negro in the South is a book written in 1907 by sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois and educator Booker T. Washington that describes the social history of African-American people in the southern United States. It is a compilation of the William Levi Bull Lectures on Christian Sociology from that year. Washington and Du Bois had recently co-contributed to the Washington-edited 1903 collection The Negro Problem.

The Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems was an annual conference held at Atlanta University, organized by W. E. B. Du Bois, and held every year from 1896 to 1914.

Caroline Phelps Stokes was a benefactor to many organizations that helped the underprivileged in the US, Africa and the Near East, supporting churches, libraries, educational establishments, orphanages, housing and more. A fund was set up after her death that continued to support her work.

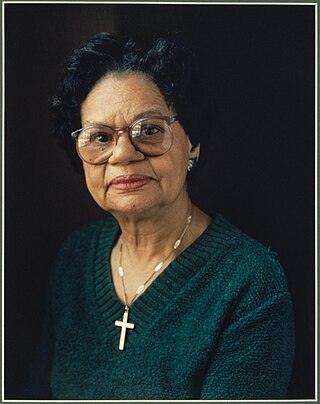

Olivia Pearl Stokes was a religious educator, ordained Baptist minister, author, administrator, and civil rights activist. As the first African American woman to receive a doctorate in religious education, Stokes was a pioneer in her field dedicated to empowering disenfranchised and underrepresented groups. A majority of her work reflects her primary role as a religious educator, her commitment to develop leadership training, and her efforts to eliminate negative stereotypes of women and African Americans. She was also an avid student of African cultures, and developed programs to promote understanding of African civilizations.

Olivia Egleston Phelps Stokes was an American writer and benefactor to many organisations that helped the underprivileged in the United States including supporting churches, libraries, educational establishments, orphanages, housing and more.