The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby go into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162 (1875), is a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that citizenship does not confer a right to vote, and therefore state laws barring women from voting are constitutionally valid. The Supreme Court upheld state court decisions in Missouri, which had refused to register a woman as a lawful voter because that state's laws allowed only men to vote.

Laura Clay, co-founder and first president of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association, was a leader of the American women's suffrage movement. She was one of the most important suffragists in the South, favoring the states' rights approach to suffrage. A powerful orator, she was active in the Democratic Party and had important leadership roles in local, state and national politics. In 1920 at the Democratic National Convention, she was one of two women, alongside Cora Wilson Stewart, to be the first women to have their names placed into nomination for the presidency at the convention of a major political party.

Virginia Louisa Minor was an American women's suffrage activist. She is best remembered as the plaintiff in Minor v. Happersett, an 1875 United States Supreme Court case in which Minor unsuccessfully argued that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution gave women the right to vote.

The 1916 Democratic National Convention was held at the St. Louis Coliseum in St. Louis, Missouri from June 14 to June 16, 1916. It resulted in the nomination of President Woodrow Wilson and Vice President Thomas R. Marshall for reelection.

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

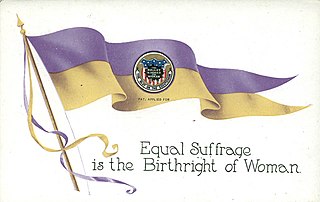

The St. Louis Equal Suffrage League was formed in 1910 in St. Louis, Missouri with the aim of "bring[ing] together men and women who are willing to consider the question of Equal Suffrage and by earnest co-operation to secure its establishment."

Francis Minor, husband of suffragist Virginia Minor, was a lawyer and a women's rights advocate. Turning Point Suffragist Memorial lists Francis along with six others as "Suffragist Men" and "the Importance of Allies."

Women's suffrage was granted in Virginia in 1920, with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The General Assembly, Virginia's governing legislative body, did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952. The argument for women's suffrage in Virginia began in 1870, but it did not gain traction until 1909 with the founding of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. Between 1912 and 1916, Virginia's suffragists would bring the issue of women's voting rights to the floor of the General Assembly three times, petitioning for an amendment to the state constitution giving women the right to vote; they were defeated each time. During this period, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia and its fellow Virginia suffragists fought against a strong anti-suffragist movement that tapped into conservative, post-Civil War values on the role of women, as well as racial fears. After achieving suffrage in August 1920, over 13,000 women registered within one month to vote for the first time in the 1920 United States presidential election.

The women's suffrage movement was active in Missouri mostly after the Civil War. There were significant developments in the St. Louis area, though groups and organized activity took place throughout the state. An early suffrage group, the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri, was formed in 1867, attracting the attention of Susan B. Anthony and leading to news items around the state. This group, the first of its kind, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly for women's suffrage and established conventions. In the early 1870s, many women voted or registered to vote as an act of civil disobedience. The suffragist Virginia Minor was one of these women when she tried to register to vote on October 15, 1872. She and her husband, Francis Minor, sued, leading to a Supreme Court case that asserted the Fourteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote. The case, Minor v. Happersett, was decided against the Minors and led suffragists in the country to pursue legislative means to grant women suffrage.

Even before women's suffrage efforts took off in Rhode Island, women were fighting for equal male suffrage during the Dorr Rebellion. Women raised money for the Dorrite cause, took political action and kept members of the rebellion in exile informed. An abolitionist, Paulina Wright Davis, chaired and attended women's rights conferences in New England and later, along with Elizabeth Buffum Chace, founded the Rhode Island Women's Suffrage Association (RIWSA) in 1868. This group petitioned the Rhode Island General Assembly for an amendment to the state constitution to provide women's suffrage. For many years, RIWSA was the major group providing women's suffrage action in Rhode Island. In 1887, a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution came up for a voter referendum. The vote, on April 6, 1887, was decisively against women's suffrage.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Rhode Island. Women's suffrage in Rhode Island started with women's rights activities, such as convention planning and publications of women's rights journals. The first women's suffrage group in Rhode Island was founded in 1868. A women's suffrage amendment was decided by referendum on April 6, 1887, but it failed by a large amount. Finally, in 1917, Rhode Island women gained the right to vote in presidential elections. On January 6, 1920, Rhode Island became the twenty-fourth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Virginia. While there were some very early efforts to support women's suffrage in Virginia, most of the activism for the vote for women occurred early in the 20th century. The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was formed in 1909 and the Virginia Branch of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage was formed in 1915. Over the next years, women held rallies, conventions and many propositions for women's suffrage were introduced in the Virginia General Assembly. Virginia didn't ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952. Native American women could not have a full vote until 1924 and African American women were effectively disenfranchised until the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965.

Women's suffrage began in Illinois began in the mid-1850s. The first women's suffrage group was formed in Earlville, Illinois, by the cousin of Susan B. Anthony, Susan Hoxie Richardson. After the Civil War, former abolitionist Mary Livermore organized the Illinois Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), which would later be renamed the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA). Frances Willard and other suffragists in the IESA worked to lobby various government entities for women's suffrage. In the 1870s, women were allowed to serve on school boards and were elected to that office. The first women to vote in Illinois were 15 women in Lombard, Illinois, led by Ellen A. Martin, who found a loophole in the law in 1891. Women were eventually allowed to vote for school offices in the 1890s. Women in Chicago and throughout Illinois fought for the right to vote based on the idea of no taxation without representation. They also continued to expand their efforts throughout the state. In 1913, women in Illinois were successful in gaining partial suffrage. They became the first women east of the Mississippi River to have the right to vote in presidential elections. Suffragists then worked to register women to vote. Both African-American and white suffragists registered women in huge numbers. In Chicago alone 200,000 women were registered to vote. After gaining partial suffrage, women in Illinois kept working towards full suffrage. The state became the first to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, passing the ratification on June 10, 1919. The League of Women Voters (LWV) was announced in Chicago on February 14, 1920.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Delaware. Suffragists in Delaware began to fight for women's suffrage in the late 1860s. Mary Ann Sorden Stuart and national suffragists lobbied the Delaware General Assembly for women's suffrage. In 1896, the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) was formed. Annual state suffrage conventions were held. There were also numerous attempts to pass an equal suffrage amendment to the Delaware State Constitution, but none were successful. In 1913, a state chapter of the Congressional Union (CU) was opened by Mabel Vernon. Delaware suffragists are involved in more militant tactics, including taking part of the Silent Sentinels. On March 22, 1920, Delaware had a special session of the General Assembly to consider ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. It was not ratified by Delaware until 1923.

In 1893, Colorado became the second state in the United States to grant women's suffrage and the first to do so through a voter referendum. Even while Colorado was a territory, lawmakers and other leaders tried to include women's suffrage in laws and later in the state constitution. The constitution did give women the right to vote in school board elections. The first voter referendum campaign was held in 1877. The Woman Suffrage Association of Colorado worked to encourage people to vote yes. Nationally-known suffragists, such as Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone spoke alongside Colorado's own Alida Avery around the state. Despite the efforts to influence voters, the referendum failed. Suffragists continued to grow support for women's right to vote. They exercised their right to vote in school board elections and ran for office. In 1893, another campaign for women's suffrage took place. Both Black and white suffragists worked to influence voters, gave speeches, and turned out on election day in a last-minute push. The effort was successful and women earned equal suffrage. In 1894, Colorado again made history by electing three women to the Colorado house of representatives. After gaining the right to vote, Colorado women continued to fight for suffrage in other states. Some women became members of the Congressional Union (CU) and pushed for a federal suffrage amendment. Colorado women also used their right to vote to pass reforms in the state and to support women candidates.