Etruscan religion comprises a set of stories, beliefs, and religious practices of the Etruscan civilization, heavily influenced by the mythology of ancient Greece, and sharing similarities with concurrent Roman mythology and religion. As the Etruscan civilization was gradually assimilated into the Roman Republic from the 4th century BC, the Etruscan religion and mythology were partially incorporated into ancient Roman culture, following the Roman tendency to absorb some of the local gods and customs of conquered lands. The first attestations of an Etruscan religion can be traced back to the Villanovan culture.

In Etruscan mythology, Charun acted as one of the psychopompoi of the underworld. He is often portrayed with Vanth, a winged figure also associated with the underworld.

In Etruscan mythology, Tuchulcha was a chthonic daemon with pointed ears, hair made of snakes, and a beak. Tuchulcha lived in the underworld known as Aita.

Vanth is a chthonic figure in Etruscan mythology shown in a variety of forms of funerary art, such as in tomb paintings and on sarcophagi.

The Book of Gates is an ancient Egyptian funerary text dating from the New Kingdom. The Book of Gates is long and detailed, consisting of one hundred scenes. It narrates the passage of a newly deceased soul into the next world journeying with the sun god, Ra, through the underworld during the hours of the night towards his resurrection. The soul is required to pass through a series of 'gates' at each hour of the journey. Each gate is guarded by a different serpent deity that is associated with a different goddess. It is important that the deceased knows the names of each guardian. Depictions of the judgment of the dead are shown in the last three hours. The text implies that some people will pass through unharmed, but others will suffer torment in a lake of fire. At the end of Ra's journey through the underworld, he emerges anew to take his place back in the sky.

QV66 is the tomb of Nefertari, the Great Wife of Pharaoh Ramesses II, in Egypt's Valley of the Queens. It was discovered by Ernesto Schiaparelli in 1904. Nefertari, which means "beautiful companion", was Ramesses II's favorite wife; he went out of his way to make this obvious, referring to her as "the one for whom the sun shines" in his writings, built the Temple of Hathor to idolize her as a deity, and commissioned portraiture wall paintings. In the Valley of the Queens, Nefertari's tomb once held the mummified body and representative symbolisms of her, consistent with most Egyptian tombs of the period. Now, everything had been looted except for two thirds of the 5,200 square feet of wall paintings. For what still remains, these wall paintings characterized Nefertari's character. Her face received particular attention to emphasize her beauty, especially the shape of her eyes, the blush of her cheeks, and her eyebrows. Some paintings were full of lines and color of red, blue, yellow, and green that portrayed exquisite directions to navigating through the afterlife to paradise.

The Tomb of the Roaring Lions is an archaeological site at the ancient city of Veii, Italy. It is best known for its well-preserved fresco paintings of four feline-like creatures, believed by archaeologists to depict lions. The tomb is believed to be one of the oldest painted tombs in the western Mediterranean, dating back to 690 BCE. The discovery of the Tomb allowed archaeologists a greater insight into funerary practices amongst the Etruscan people, while providing insight into art movements around this period of time. The fresco paintings on the wall of the tomb are a product of advances in trade that allowed artists in Veii to be exposed to art making practices and styles of drawing originating from different cultures, in particular geometric art movements in Greece. The lions were originally assumed to be caricatures of lions – created by artists who had most likely never seen the real animal in flesh before.

The Sarcophagus of the Spouses is a tomb effigy considered one of the masterpieces of Etruscan art. The Etruscans lived in Italy between two main rivers, the Arno and the Tiber, and were in contact with the Ancient Greeks through trade, mainly during the Orientalizing and Archaic periods. The Etruscans were well known for their terracotta sculptures and funerary art, predominantly sarcophagi and urns. This sarcophagus is a late sixth-century BCE Etruscan anthropoid sarcophagus found at the Banditaccia necropolis in Caere, and is now located in the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia, Rome.

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 10th and 1st centuries BC. From around 750 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta, wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.

The Tomb of Orcus, sometimes called the Tomb of Murina, is a 4th-century BC Etruscan hypogeum in Tarquinia, Italy. Discovered in 1868, it displays Hellenistic influences in its remarkable murals, which include the portrait of Velia Velcha, an Etruscan noblewoman, and the only known pictorial representation of the daemon Tuchulcha. In general, the murals are noted for their depiction of death, evil, and unhappiness.

The Tomb of the Whipping is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy. It is dated to approximately 490 BC and named after a fresco of two men who flog a woman in an erotic context. The tomb was discovered and excavated in 1960 by Carlo Maurilio Lerici. Most of the paintings are badly damaged.

The Tomb of the Leopards is an Etruscan burial chamber so called for the confronted leopards painted above a banquet scene. The tomb is located within the Necropolis of Monterozzi, near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy, and dates to around 470–450 BC. The painting is one of the best-preserved murals of Tarquinia, and is known for "its lively coloring, and its animated depictions rich with gestures," and is influenced by the Greek-Attic art of the first quarter of the fifth century BC.

The Tomb of the Bulls is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy. It was discovered in 1892 and has been dated back to either 540–530 BC or 530–520 BC. According to an inscription Arath Spuriana apparently commissioned the construction of the tomb. It is named after the two bulls which appear on one of its frescoes. It is the earliest example of a tomb with complex frescoes in the necropolis, and the stylistic elements are derived from Ionian Greek culture. Along with the frescoes of the Tomb of the Whipping these paintings are relatively rare examples of explicit sexual scenes in Etruscan art, which were far more common in Ancient Greek art.

The Monterozzi necropolis is an Etruscan necropolis on a hill east of Tarquinia in Lazio, Italy. The necropolis has about 6,000 graves, the oldest of which dates to the 7th century BC. About 200 of the tomb chambers are decorated with frescos.

The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing, formerly known as the Tomb of the Hunter, is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy. It was discovered in 1873 and has been dated variously to about 530–520 BC, 520 BC, 510 BC or 510–500 BC. Stephan Steingräber calls it "unquestionably one of the most beautiful and original of the Tarquinian tombs from the Late Archaic period." R. Ross Holloway emphasizes the reduction of humans to small figures in a large natural environment. There were no precedents for this in Ancient Greek art or in the Etruscan art it influenced. It was a major development in the history of ancient painting.

The Tomb of the Triclinium ) is an Etruscan tomb in the Necropolis of Monterozzi dated to approximately 470 BC. The tomb is named after the Roman triclinium, a type of formal dining room, which appears in the frescoes of the tomb. It has been described as one of the most famous of all Etruscan tombs.

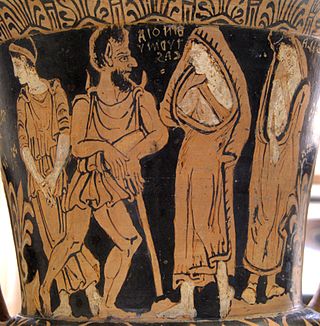

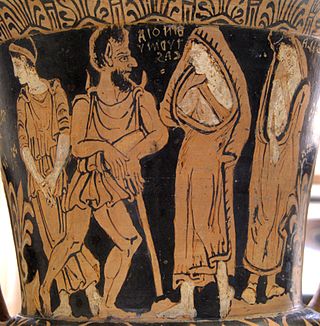

The Tomb of the Dancers or Tomb of the Dancing Women is a Peucetian tomb in Ruvo di Puglia, Italy. It was discovered in the Corso Cotugno necropolis in November 1833. The date of its construction is uncertain, dates ranging from the end of the fifth century BC to the mid-fourth century BC have been proposed. In any case, the tomb's frescoes are the oldest example of figurative painting in Apulia, together with another tomb in Gravina di Puglia. The Peucetians borrowed the practice of painting tombs from the Etruscans, who had an important influence on their culture. The tomb is named after the dancing women which appear on the frescoes in the tomb. The panels with the frescoes are now exhibited in the Naples National Archaeological Museum, inv. 9353.

The Tomb of the Reliefs is an Etruscan tomb in the Banditaccia necropolis near Cerveteri, Italy.

The Tomb of the Augurs is an Etruscan burial chamber so called because of a misinterpretation of one of the fresco figures on the right wall thought to be a Roman priest known as an augur. The tomb is located within the Necropolis of Monterozzi near Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy, and dates to around 530-520 BC. This tomb is one of the first tombs in Tarquinia to have figural decoration on all four walls of its main or only chamber. The wall decoration was frescoed between 530-520 BC by an Ionian Greek painter, perhaps from Phocaea, whose style was associated with that of the Northern Ionic workers active in Elmali. This tomb is also the first time a theme not of mythology, but instead depictions of funerary rites and funerary games are seen.

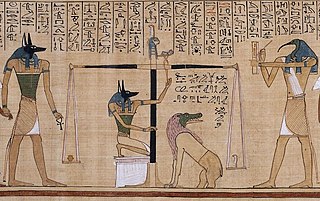

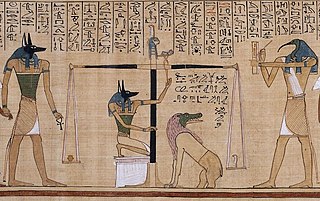

Ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs were centered around a variety of complex rituals that were influenced by many aspects of Egyptian culture. Religion was a major contributor, since it was an important social practice that bound all Egyptians together. For instance, many of the Egyptian gods played roles in guiding the souls of the dead through the afterlife. With the evolution of writing, religious ideals were recorded and quickly spread throughout the Egyptian community. The solidification and commencement of these doctrines were formed in the creation of afterlife texts which illustrated and explained what the dead would need to know in order to complete the journey safely.