Related Research Articles

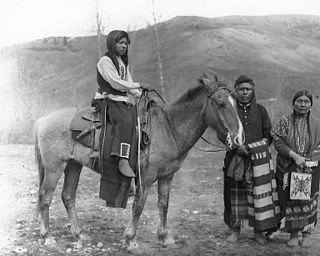

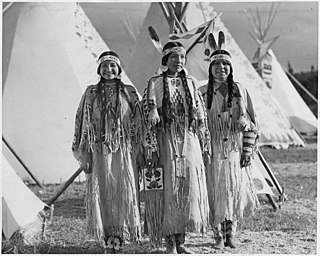

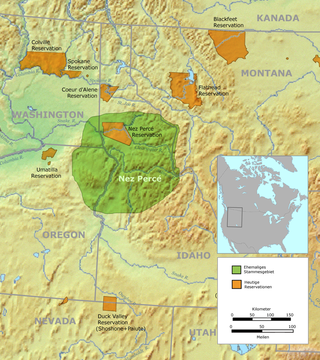

The Nez Perce are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who still live on a fraction of the lands on the southeastern Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest. This region has been occupied for at least 11,500 years.

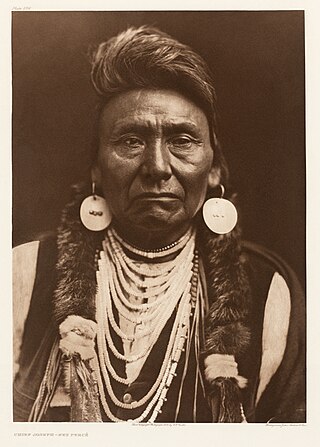

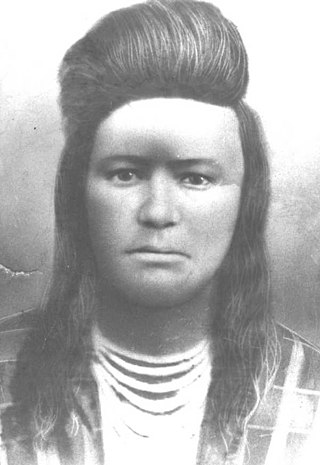

Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, popularly known as Chief Joseph, Young Joseph, or Joseph the Younger, was a leader of the wal-lam-wat-kain (Wallowa) band of Nez Perce, a Native American tribe of the interior Pacific Northwest region of the United States, in the latter half of the 19th century. He succeeded his father tuekakas in the early 1870s.

Targhee Pass is a mountain pass in the western United States on the Continental Divide. It is located along the border between southeastern Idaho and southwestern Montana, in the Henrys Lake Mountains at an elevation of 7,072 feet (2,156 m) above sea level. The pass is named for a Bannock chief.

The Nez Perce War was an armed conflict in 1877 in the Western United States that pitted several bands of the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans and their allies, a small band of the Palouse tribe led by Red Echo (Hahtalekin) and Bald Head, against the United States Army. Fought between June and October, the conflict stemmed from the refusal of several bands of the Nez Perce, dubbed "non-treaty Indians," to give up their ancestral lands in the Pacific Northwest and move to an Indian reservation in Idaho Territory. This forced removal was in violation of the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla, which granted the tribe 7.5 million acres of their ancestral lands and the right to hunt and fish on lands ceded to the U.S. government.

The Palouse are a Sahaptin tribe recognized in the Treaty of 1855 with the United States along with the Yakama. It was negotiated at the 1855 Walla Walla Council. A variant spelling is Palus. Today they are enrolled in the federally recognized Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation and some are also represented by the Colville Confederated Tribes, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Nez Perce Tribe.

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans during the Nez Perce War. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Nez Perce withdrew in good order from the battlefield and continued their long fighting retreat that would result in their attempt to reach Canada and asylum.

The Battle of the Clearwater was a battle in the Idaho Territory between the Nez Perce under Chief Joseph and the United States Army. Under General O. O. Howard, the army surprised a Nez Perce village; the Nez Perce counter-attacked and inflicted significant casualties on the soldiers, but were forced to abandon the village.

The Battle of Bear Paw was the final engagement of the Nez Perce War of 1877. Following a 1,200-mile (1,900 km) running fight from north central Idaho Territory over the previous four months, the U.S. Army managed to corner most of the Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph in early October 1877 in northern Montana Territory, just 42 miles (68 km) south of the border with Canada, where the Nez Perce intended to seek refuge from persecution by the U.S. government.

The Battle of Camas Creek, August 20, 1877, was a raid by the Nez Perce people on a United States Army encampment in Idaho Territory and a subsequent battle during the Nez Perce War. The Nez Perce defeated three companies of U.S. cavalry and continued their fighting retreat to escape the army.

Big Hole National Battlefield preserves a battlefield in the western United States, located in Beaverhead County, Montana. In 1877, the Nez Perce fought a delaying action against the U.S. Army's 7th Infantry Regiment here on August 9 and 10, during their failed attempt to escape to Canada. This action, the Battle of the Big Hole, was the largest battle fought between the Nez Perce and U.S. Government forces in the five-month conflict known as the Nez Perce War.

The Sahaptin are a number of Native American tribes who speak dialects of the Sahaptin language. The Sahaptin tribes inhabited territory along the Columbia River and its tributaries in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Sahaptin-speaking peoples included the Klickitat, Kittitas, Yakama, Wanapum, Palus, Lower Snake, Skinpah, Walla Walla, Umatilla, Tenino, and Nez Perce.

The Battle of White Bird Canyon was fought on June 17, 1877, in Idaho Territory. White Bird Canyon was the opening battle of the Nez Perce War between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States. The battle was a significant defeat of the U.S. Army. It took place in the western part of present-day Idaho County, southwest of the city of Grangeville.

The Battle of Canyon Creek was a military engagement in Montana Territory between the Nez Perce Indians and the United States Army's 7th Cavalry. The battle was part of the larger Indian Wars of the latter 19th century and the immediate Nez Perce War. It took place on September 13, 1877, west of present-day Billings in Yellowstone County, in the canyons and benches around Canyon Creek.

Weyekin or wyakin is a Nez Perce word for a type of spiritual being.

Lucullus Virgil McWhorter was an American farmer and frontiersman who documented the historical Native American tribes in West Virginia and the modern-day Plateau Native Americans in Washington state. After living in West Virginia and Ohio, in 1903 he moved to the frontier of Yakima, Washington, in the eastern part of the state. He became a rancher and activist, learning much from his Yakama Nation neighbors and becoming an activist for them. In 1914 he was adopted as an honorary member of the Yakama, after helping over several years to defeat a federal bill that would have required them to give up much of their land in order to get any irrigation rights. They named him Hemene Ka-Wan,, meaning Old Wolf.

Yellow Wolf or He–Mene Mox Mox was a Nez Perce warrior who fought in the Nez Perce War of 1877. In his old age, he decided to give the war a Native American perspective. From their meeting in 1907 till his death in 1935, Yellow Wolf talked annually to Lucullus Virgil McWhorter, who wrote a book for him, Yellow Wolf: His Own Story. He is notable as one of the few members of the defeated Nez Perce to talk openly to strangers and tell their story to the world.

Ollokot, was a war leader of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce Indians and a leader of the young warriors in the Nez Perce War in 1877.

Fort Fizzle was a temporary military barricade in the western United States, erected by the U.S. Army in July 1877 in Montana Territory. Its purpose was to intercept the Nez Perce in their flight from north central Idaho Territory over Lolo Pass into the Bitterroot Valley of western Montana. The name describes the effectiveness of the fort.

The Nez Perce native Americans fled through Yellowstone National Park between August 20 and Sept 7, during the Nez Perce War in 1877. As the U.S. army pursued the Nez Perce through the park, a number of hostile and sometimes deadly encounters between park visitors and the Indians occurred. Eventually, the army's pursuit forced the Nez Perce off the Yellowstone plateau and into forces arrayed to capture or destroy them when they emerged from the mountains of Yellowstone onto the valley of Clark's Fork of the Yellowstone River.

The Attack on Looking Glass Camp was a military attack carried out on July 1, 1877 as part of the Nez Perce War by Captain Stephen G. Whipple of the United States Army on the village of the Native American chief Looking Glass, located near the Clearwater River, near the present-day town of Kooskia. Glass had refused to join the other Nez Perce factions hostile to the Americans, so General Oliver Otis Howard, relying on reports that Glass posed a threat, gave the order to arrest him and his group.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 McWhorter, Lucullus Virgil (1940). Yellow Wolf: His Own Story. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, Ltd. pp. 33–51.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Forczyk, Robert (2011). Nez Perce 1877: The Last Flight . Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-84908-191-7.

- ↑ Hampton, Bruce. Children of Grace: The Nez Perce War of 1877, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1994, p 292.

- ↑ Jerome A. Greene and Alvin M. Josephy. Nez Perce Summer, 1877: The Us Army and the Nee-Me-Poo Crisis, Montana Historical Society Press, 2000, p 291.

- 1 2 3 4 McWhorter, Lucullus Virgil (1952). !: Nez Perce history and legend. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, Ltd. pp. 162–163.

- ↑ West, Elliott (2009). The Last Indian War. Oxford University Press. p. 123.

- ↑ Henry, Will (2007). From Where the Sun Now Stands. New York: Madison Park Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Henry, Will (2007). From Where the Sun Now Stands. New York: Madison Park Press. p. 28.

- ↑ Henry, Will (2007). From Where the Sun Now Stands. New York: Madison Park Press. p. 37.

- ↑ Henry, Will (1996). The Bear Paw Horses. Leisure Books. p. 270.

- ↑ Fisher, Andrew H. "American Indian Heritage Month: Commemoration vs. Exploitation" . Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ↑ Aoki, Haruo (1994). Nez Percé Dictionary. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. p. 792. ISBN 0-520-09763-7.