Heidi is a work of children's fiction published between 1880 and 1881 by Swiss author Johanna Spyri, originally published in two parts as Heidi: Her Years of Wandering and Learning and Heidi: How She Used What She Learned. It is a novel about the events in the life of a 5-year-old girl in her paternal grandfather's care in the Swiss Alps. It was written as a book "for children and those who love children".

Afro-Asians, African Asians, Blasians, or simply Black Asians are people of mixed Asian and African ancestry. Historically, Afro-Asian populations have been marginalised as a result of human migration and social conflict.

Marianne Hoppe was a German theatre and film actress.

Afro-Germans or Black Germans are Germans of Sub-Saharan African descent.

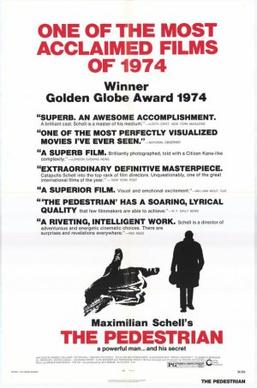

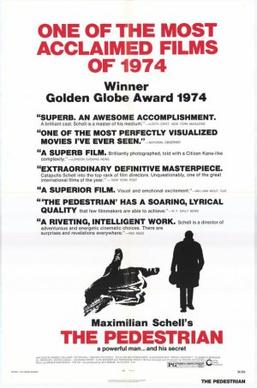

The Pedestrian is a 1973 film directed by Maximilian Schell. It is about the trial of an elderly war criminal. The film was a co-production between companies in Germany, Switzerland and Israel; the movie was distributed in the United States by Cinerama Releasing Corporation.

Paul Hermann Bildt was a German film actor. He appeared in more than 180 films between 1910 and 1956. He was born in Berlin and died in Zehlendorf, West Berlin.

The Ruler is a 1937 German drama film directed by Veit Harlan. It was adapted from the play of the same name by Gerhart Hauptmann. Erwin Leiser calls it a propagandistic demonstration of the Führerprinzip of Nazi Germany. The film's sets were designed by the art director Robert Herlth. Location shooting took place around Oberhausen and Pompeii near Naples. It premiered at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo in Berlin.

Margarete Schön was a German stage and film actress whose career spanned nearly fifty years. She is internationally recognized for her role as Kriemhild in director Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen series of two silent fantasy films, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge.

Brown Babies is a term used for children born to black soldiers and white women during and after the Second World War. Other names include "war babies" and "occupation babies." In Germany they were known as Mischlingskinder, a term first used under the Nazi regime for children of mixed Jewish-German parentage. As of 1955, African-American soldiers had fathered about 5,000 children in the American Zone of Occupied Germany. In Occupied Austria, estimates of children born to Austrian women and Allied soldiers ranged between 8,000 and 30,000, perhaps 500 of them biracial. In the United Kingdom, West Indian members of the British military, as well as African-American soldiers in the US Army, fathered 2,000 children during and after the war. A much smaller and unknown number, probably in the low hundreds, was born in the Netherlands, but the lives of some have been followed into their old age and it is possible to have a better understanding of the experience that would unfold for all of the Brown Babies of World War II Europe.

Maria Matray was a German screenwriter and film actress. Matray became a star of late Weimar cinema.

The Girl at the Reception is a 1940 German drama film directed by Gerhard Lamprecht and starring Magda Schneider, Heinz Engelmann, and Carsta Löck.

Bachelors' Paradise is a 1939 German comedy film directed by Kurt Hoffmann and starring Heinz Rühmann, Josef Sieber, and Hans Brausewetter. It was based on a novel by Johannes Boldt. It was shot at the Babelsberg Studios in Berlin with sets designed by the art director Willi Herrmann. The film featured the popular song "Das kann doch einen Seemann nicht erschüttern".

The Impossible Woman is a 1936 German romance film directed by Johannes Meyer and starring Dorothea Wieck, Gustav Fröhlich and Gina Falckenberg. It was shot at the Johannisthal Studios in Berlin and partly on location in Romania. It was based on the novel Madame will nicht heiraten by Mia Fellmann.

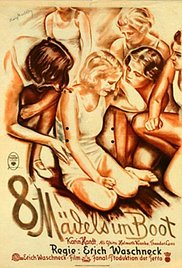

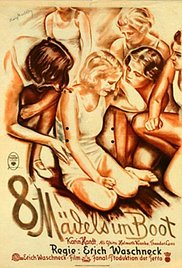

Eight Girls in a Boat is a 1932 German musical film directed by Erich Waschneck and starring Karin Hardt, Theodor Loos, and Helmuth Kionka. It was shot at the Tempelhof Studios in Berlin. The film's sets were designed by art director Alfred Junge.

Erika "Ika" Hügel-Marshall was a German author and activist. She was active in the Afro-German women's movement organization ADEFRA. Her autobiography, Daheim unterwegs. Ein deutsches Leben, discusses racism in Germany and her search for a family identity. She was influenced by and praised the work of her friend, American activist Audre Lorde. She and her partner Dagmar Schultz worked with Lorde.

Hannele's Journey to Heaven is a 1922 German silent film directed by Urban Gad and starring Margarete Schlegel, Margarete Schön and Hermann Vallentin. The film is based on the play, The Assumption of Hannele by German author Gerhart Hauptmann. It was remade as a sound film in 1934.

Royal Children is a 1950 West German comedy film directed by Helmut Käutner and starring Jenny Jugo, Peter van Eyck and Hedwig Wangel. It was shot at the Bavaria Studios in Munich and on location in Bad Wimpfen and at Hornberg Castle. The film's sets were designed by the art director Bruno Monden and Hermann Warm. It was a major commercial failure on release.

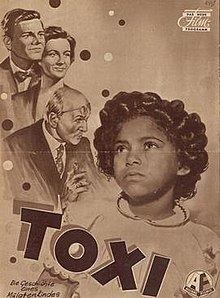

Elfie (Elfriede) Fiegert - born April 1946, in Freising, Bavaria, West Germany - is an Afro-German film actor who became famous as a child actor for playing the lead role in the film Toxi (1952) filmed when she was five years old. This was followed in 1955 with the film The Dark Star which has erroneously been described as sequel. At the age of seventeen she had a small role in The House in Montevideo (1963).

The Dark Star is a 1955 West German drama film directed by Hermann Kugelstadt and starring Elfie Fiegert, Ilse Steppat and Viktor Staal.

Leila Negra, the stage name of Marie Nejar is an Afro-German singer and actress. She began her career as a child film actor in the 1940s, became a singer after World War II, and left performing in the late 1950s to become a nurse.