Erosion is the action of surface processes that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is distinct from weathering which involves no movement. Removal of rock or soil as clastic sediment is referred to as physical or mechanical erosion; this contrasts with chemical erosion, where soil or rock material is removed from an area by dissolution. Eroded sediment or solutes may be transported just a few millimetres, or for thousands of kilometres.

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles to settle in place. The particles that form a sedimentary rock are called sediment, and may be composed of geological detritus (minerals) or biological detritus. The geological detritus originated from weathering and erosion of existing rocks, or from the solidification of molten lava blobs erupted by volcanoes. The geological detritus is transported to the place of deposition by water, wind, ice or mass movement, which are called agents of denudation. Biological detritus was formed by bodies and parts of dead aquatic organisms, as well as their fecal mass, suspended in water and slowly piling up on the floor of water bodies. Sedimentation may also occur as dissolved minerals precipitate from water solution.

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand and silt can be carried in suspension in river water and on reaching the sea bed deposited by sedimentation; if buried, they may eventually become sandstone and siltstone through lithification.

Geomorphology is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or near Earth's surface. Geomorphologists seek to understand why landscapes look the way they do, to understand landform and terrain history and dynamics and to predict changes through a combination of field observations, physical experiments and numerical modeling. Geomorphologists work within disciplines such as physical geography, geology, geodesy, engineering geology, archaeology, climatology, and geotechnical engineering. This broad base of interests contributes to many research styles and interests within the field.

A braided river, or braided channel, consists of a network of river channels separated by small, often temporary, islands called braid bars or, in British English usage, aits or eyots.

A river delta is a landform shaped like a triangle, created by the deposition of sediment that is carried by a river and enters slower-moving or stagnant water. This occurs when a river enters an ocean, sea, estuary, lake, reservoir, or another river that cannot carry away the supplied sediment. It is so named because its triangle shape resembles the Greek letter Delta. The size and shape of a delta are controlled by the balance between watershed processes that supply sediment, and receiving basin processes that redistribute, sequester, and export that sediment. The size, geometry, and location of the receiving basin also plays an important role in delta evolution.

In geography and geology, fluvial processes are associated with rivers and streams and the deposits and landforms created by them. When the stream or rivers are associated with glaciers, ice sheets, or ice caps, the term glaciofluvial or fluvioglacial is used.

Deposition is the geological process in which sediments, soil and rocks are added to a landform or landmass. Wind, ice, water, and gravity transport previously weathered surface material, which, at the loss of enough kinetic energy in the fluid, is deposited, building up layers of sediment.

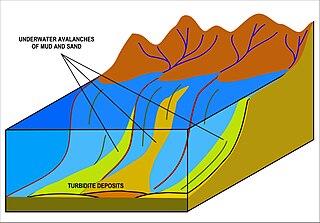

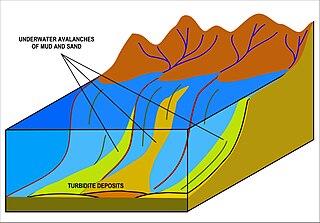

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Hydraulic action, most generally, is the ability of moving water to dislodge and transport rock particles. This includes a number of specific erosional processes, including abrasion, at facilitated erosion, such as static erosion where water leaches salts and floats off organic material from unconsolidated sediments, and from chemical erosion more often called chemical weathering. It is a mechanical process, in which the moving water current flows against the banks and bed of a river, thereby removing rock particles. A primary example of hydraulic action is a wave striking a cliff face which compresses the air in cracks of the rocks. This exerts pressure on the surrounding rock which can progressively crack, break, splinter and detach rock particles. This is followed by the decompression of the air as the wave retreats which can occur suddenly with explosive force which additionally weakens the rock. Cracks are gradually widened so each wave compresses more air, increasing the explosive force of its release. Thus, the effect intensifies in a 'positive feedback' system. Over time, as the cracks may grow they sometimes form a sea cave. The broken pieces that fall off produce two additional types of erosion, abrasion (sandpapering) and attrition. In corrasion, the newly formed chunks are thrown against the rock face. Attrition is a similar effect caused by eroded particles after they fall to the sea bed where they are subjected to further wave action. In coastal areas wave hydraulic action is often the most important form of erosion.

In geology, a graded bed is one characterized by a systematic change in grain or clast size from one side of the bed to the other. Most commonly this takes the form of normal grading, with coarser sediments at the base, which grade upward into progressively finer ones. Such a bed is also described as fining upward. Normally graded beds generally represent depositional environments which decrease in transport energy as time passes, but these beds can also form during rapid depositional events. They are perhaps best represented in turbidite strata, where they indicate a sudden strong current that deposits heavy, coarse sediments first, with finer ones following as the current weakens. They can also form in terrestrial stream deposits.

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles (sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and the movement of the fluid in which the sediment is entrained. Sediment transport occurs in natural systems where the particles are clastic rocks, mud, or clay; the fluid is air, water, or ice; and the force of gravity acts to move the particles along the sloping surface on which they are resting. Sediment transport due to fluid motion occurs in rivers, oceans, lakes, seas, and other bodies of water due to currents and tides. Transport is also caused by glaciers as they flow, and on terrestrial surfaces under the influence of wind. Sediment transport due only to gravity can occur on sloping surfaces in general, including hillslopes, scarps, cliffs, and the continental shelf—continental slope boundary.

The suspended load of a flow of fluid, such as a river, is the portion of its sediment uplifted by the fluid's flow in the process of sediment transportation. It is kept suspended by the fluid's turbulence. The suspended load generally consists of smaller particles, like clay, silt, and fine sands.

In hydrology and geography, armor is the association of surface pebbles, rocks or boulders with stream beds or beaches. Most commonly hydrological armor occurs naturally; however, a man-made form is usually called riprap, when shorelines or stream banks are fortified for erosion protection with large boulders or sizable manufactured concrete objects. When armor is associated with beaches in the form of pebbles to medium-sized stones grading from two to 200 millimeters across, the resulting landform is often termed a shingle beach. Hydrological modeling indicates that stream armor typically persists in a flood stage environment.

Stream load is a geologic term referring to the solid matter carried by a stream. Erosion and bed shear stress continually remove mineral material from the bed and banks of the stream channel, adding this material to the regular flow of water. The amount of solid load that a stream can carry, or stream capacity, is measured in metric tons per day, passing a given location. Stream capacity is dependent upon the stream's velocity, the amount of water flow, and the gradation.

A bedrock river is a river that has little to no alluvium mantling the bedrock over which it flows. However, most bedrock rivers are not pure forms; they are a combination of a bedrock channel and an alluvial channel. The way one can distinguish between bedrock rivers and alluvial rivers is through the extent of sediment cover.

In hydrology stream competency, also known as stream competence, is a measure of the maximum size of particles a stream can transport. The particles are made up of grain sizes ranging from large to small and include boulders, rocks, pebbles, sand, silt, and clay. These particles make up the bed load of the stream. Stream competence was originally simplified by the “sixth-power-law,” which states the mass of a particle that can be moved is proportional to the velocity of the river raised to the sixth power. This refers to the stream bed velocity which is difficult to measure or estimate due to the many factors that cause slight variances in stream velocities.

A sediment gravity flow is one of several types of sediment transport mechanisms, of which most geologists recognize four principal processes. These flows are differentiated by their dominant sediment support mechanisms, which can be difficult to distinguish as flows can be in transition from one type to the next as they evolve downslope.

The Lowe sequence describes a set of sedimentary structures in turbidite sandstone beds that are deposited by high-density turbidity currents. It is intended to complement, not replace, the better known Bouma sequence, which applies primarily to turbidites deposited by low-density turbidity currents.

A grain flow is a type of sediment-gravity flow in which the fluid can be either air or water, acts only as a lubricant, and grains within the flow remain in suspension due to grain-to-grain collisions that generate a dispersive pressure to prevent further settling. Grain flows are very common in aeolian settings as grain avalanches on the slip faces of sand dunes. By contrast, pure grain flows are rare in subaqueous settings, where the grains in a flow are generally held in suspension dominantly by traction, saltation, fluid turbulence and/or grain buoyancy when the grains are floating in the clay matrix of a mud flow. However, grain-to-grain collisions are very important as a contributing process of sediment support in subaqueous, sand-rich, high-density turbidity currents. The high concentrations of sand that develop at the base of high-density flows brings grains close enough together that frequent grain-to grain collisions are inevitable and result in layers of sediment that are inverse graded as the smaller grains are able to fall in between larger grains and settle out beneath them.