Emperor Ōgimachi was the 106th Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. He reigned from November 17, 1557, to his abdication on December 17, 1586, corresponding to the transition between the Sengoku period of the Muromachi bakufu and the dawn of the new Azuchi–Momoyama period. His personal name was Michihito (方仁).

The Shin Kokin Wakashū, also known in abbreviated form as the Shin Kokinshū (新古今集) or even conversationally as the Shin Kokin, is the eighth imperial anthology of waka poetry compiled by the Japanese court, beginning with the Kokin Wakashū circa 905 and ending with the Shinshokukokin Wakashū circa 1439. The name can be literally translated as "New Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems" and bears an intentional resemblance to that of the first anthology. Together with the Man'yōshū and the Kokinshū, the Shin Kokinshū is widely considered to be one of the three most influential poetic anthologies in Japanese literary history. It was commissioned in 1201 by the retired emperor Go-Toba, who established a new Bureau of Poetry at his Nijō palace with eleven Fellows, headed by Fujiwara no Yoshitsune, for the purpose of conducting poetry contests and compiling the anthology. Despite its emphasis on contemporary poets, the Shin Kokinshū covered a broader range of poetic ages than the Kokinshū, including ancient poems that the editors of the first anthology had deliberately excluded. It was officially presented in 1205, on the 300th anniversary of the completion of the Kokinshū.

Hyakunin Isshu (百人一首) is a classical Japanese anthology of one hundred Japanese waka by one hundred poets. Hyakunin isshu can be translated to "one hundred people, one poem [each]"; it can also refer to the card game of uta-garuta, which uses a deck composed of cards based on the Hyakunin Isshu.

Fujiwara no Sadaie (藤原定家), better-known as Fujiwara no Teika, was a Japanese anthologist, calligrapher, literary critic, novelist, poet, and scribe of the late Heian and early Kamakura periods. His influence was enormous, and he is counted as among the greatest of Japanese poets, and perhaps the greatest master of the waka form – an ancient poetic form consisting of five lines with a total of 31 syllables.

The Sarashina Diary is a memoir written by the daughter of Sugawara no Takasue, a lady-in-waiting of Heian-period Japan. Her work stands out for its descriptions of her travels and pilgrimages and is unique in the literature of the period, as well as one of the first in the genre of travel writing. Lady Sarashina was a niece on her mother's side of Michitsuna's mother, author of another famous diary of the period, the Kagerō Nikki. Other than the Sarashina Diary, she may also have authored Hamamatsu Chūnagon Monogatari, Mizukara kuyuru (Self-reproach), the Tale of Nezame, and the Tale of Asakura.

This page is part of the List of years in poetry. The List of years in poetry and List of years in literature provide snapshots of developments in poetry and literature worldwide in a given year, decade or century, and allow easy access to a wide range of Wikipedia articles about movements, writers, works and developments in any timeframe. Please help to build these lists by adding and updating entries as you use them. You can access pages for individual years within the century through the navigational template at the bottom of this page, and you can access pages for other centuries through the navigational template to the right. To access the poetry pages by way of a single chart, please see the Centuries in poetry page or the List of years in poetry page.

Fujiwara no Kintō, also known as Shijō-dainagon, was a Japanese poet, admired by his contemporaries and a court bureaucrat of the Heian period. His father was the regent Fujiwara no Yoritada and his son Fujiwara no Sadayori. An exemplary calligrapher and poet, he is mentioned in works by Murasaki Shikibu, Sei Shōnagon and in a number of other major chronicles and texts.

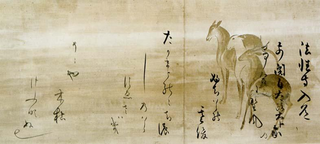

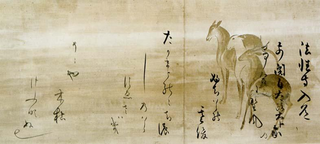

The Thirty-Six Immortals of Poetry are a group of Japanese poets of the Asuka, Nara, and Heian periods selected by Fujiwara no Kintō as exemplars of Japanese poetic ability. The oldest surviving collection of the 36 poets' works is Nishi Honganji Sanju-rokunin Kashu of 1113. Similar groups of Japanese poets include the Kamakura period Nyōbō Sanjūrokkasen (女房三十六歌仙), composed by court ladies exclusively, and the Chūko Sanjūrokkasen (中古三十六歌仙), or Thirty-Six Heian-era Immortals of Poetry, selected by Fujiwara no Norikane (1107–1165). This list superseded an older group called the Six Immortals of Poetry.

Poetic diary or Nikki bungaku (日記文学) is a Japanese literary genre, dating back to Ki no Tsurayuki's Tosa Nikki, compiled in roughly 935. Nikki bungaku is a genre including prominent works such as the Tosa Nikki, Kagerō Nikki, and Murasaki Shikibu Nikki. While diaries began as records imitating daily logs kept by Chinese government officials, private and literary diaries emerged and flourished during the Heian period.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

The Fujiwara Hok-ke was cadet branch of the Fujiwara clan of Japan.

Waka is a type of poetry in classical Japanese literature. Although waka in modern Japanese is written as 和歌, in the past it was also written as 倭歌, and a variant name is yamato-uta (大和歌).

Heian literature or Chūko literature refers to Japanese literature of the Heian period, running from 794 to 1185. This article summarizes its history and development.

Minamoto no Michichika was a Japanese noble and statesman of the late Heian period and early Kamakura period. Serving in the courts of seven different emperors, he brought the Murakami Genji to the peak of their success. He is also commonly known as Tsuchimikado Motochika, and in Sōtō Zen buddhism as Koga no Michichika.

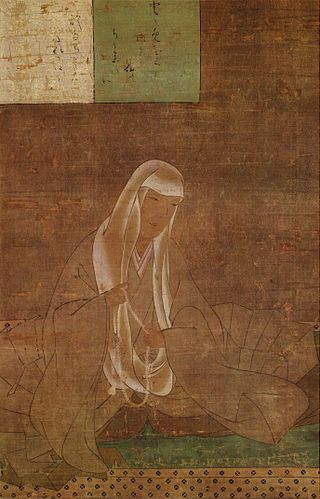

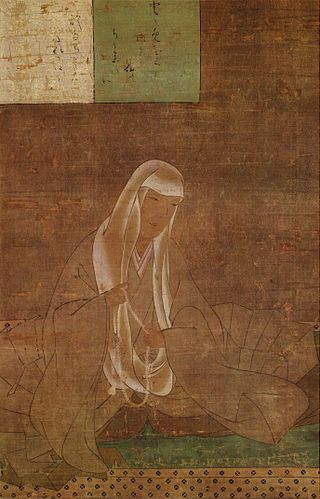

Abutsu-ni was a Japanese poet and nun. She served as a lady-in-waiting to Princess Kuni-Naishinnō, later known as Empress Ankamon-in. In approximately 1250 she married fellow poet Fujiwara no Tameie. She had two children with him. Following his death in 1275, she became a nun. A dispute over her son's inheritance led her, in either 1277 or 1279, to travel from Kyoto to Kamakura in order to plead on her son's behalf. Her account of this journey, told in poems and letters, was published as Izayoi nikki, her most well-known work.

The Tale of Genji is one of the best-known works of classical Japanese literature, and the number of manuscript copies of it is very large. It was originally written by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the Heian court, at the beginning of the eleventh century, but the earliest extant manuscript was copied by Fujiwara no Teika roughly two centuries later.

Japan's medieval period was a transitional period for the nation's literature. Kyoto ceased being the sole literary centre as important writers and readerships appeared throughout the country, and a wider variety of genres and literary forms developed accordingly, such as the gunki monogatari and otogi-zōshi prose narratives, and renga linked verse, as well as various theatrical forms such as noh. Medieval Japanese literature can be broadly divided into two periods: the early and late middle ages, the former lasting roughly 150 years from the late 12th to the mid-14th century, and the latter until the end of the 16th century.

The Thirty-Six Immortal Women Poets is a canon of Japanese poets who were anthologized in the middle Kamakura period. The compiler and exact date of the canon's construction is unknown, but its reference is subsequently noted in the Gunsho Ruijū, volume 13.