The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians, are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovene as their native language. According to ethnic classification based on language, they are closely related to other South Slavic ethnic groups, as well as more distantly to West Slavs.

Boris Pahor, OMRI was a Slovene novelist from Trieste, Italy, who was best known for his heartfelt descriptions of life as a member of the Slovenian minority in pre–Second World War increasingly fascist Italy as well as a Nazi concentration camp survivor. In his novel Necropolis he visits the Natzweiler-Struthof camp twenty years after his relocation to Dachau. Following Dachau, he was relocated three more times: to Mittelbau-Dora, to Harzungen, and finally to Bergen-Belsen, which was liberated on 15 April 1945.

The Julian March, also called Julian Venetia, is an area of southern Central Europe which is currently divided among Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia. The term was coined in 1863 by the Italian linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli, a native of the area, to demonstrate that the Austrian Littoral, Veneto, Friuli, and Trentino shared a common Italian linguistic identity. Ascoli emphasized the Augustan partition of Roman Italy at the beginning of the Empire, when Venetia et Histria was Regio X.

The Slovene Littoral, or simply Littoral, is one of the traditional regions of Slovenia. The littoral in its name – for a coastal-adjacent area – recalls the former Austrian Littoral, the Habsburg possessions on the upper Adriatic coast, of which the Slovene Littoral was part. Today, the Littoral is often associated with the Slovenian ethnic territory that, in the first half of the 20th century, found itself in Italy to the west of the Rapallo Border, which separated a quarter of Slovenes from the rest of the nation, and was strongly influenced by Italian fascism.

Maximilian Fabiani, commonly known as Max Fabiani was an Italian architect, born in the village of Kobdilj near Štanjel on the Karst Plateau, County of Gorizia and Gradisca, in present-day Slovenia. Together with Ciril Metod Koch and Ivan Vancaš, he introduced the Vienna Secession style of architecture in Slovenia.

Opicina, formerly Poggioreale del Carso in Italian, is a town in northeastern Italy, close to the Slovenian border at Fernetti. Opicina is a frazione of the comune of Trieste, the provincial and regional capital. The town has a large Slovene population, with Slovenian being widely used alongside Italian in private and public institutions. The first town near Opicina is Sežana in Slovenia, there is also the next railway station.

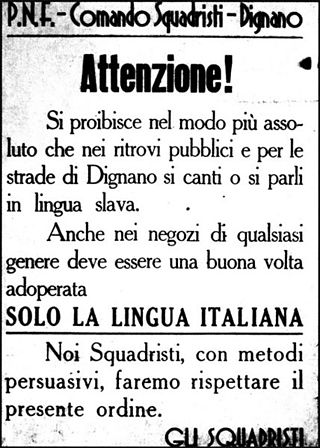

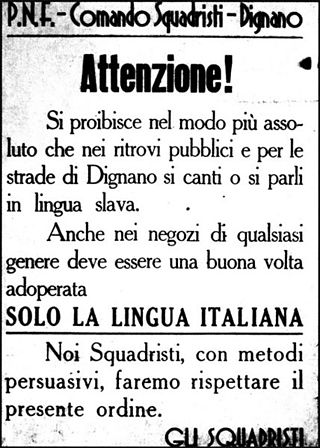

Italianization is the spread of Italian culture, language and identity by way of integration or assimilation. It is also known for a process organized by the Kingdom of Italy to force cultural and ethnic assimilation of the native populations living, primarily, in the former Austro-Hungarian territories that were transferred to Italy after World War I in exchange for Italy having joined the Triple Entente in 1915; this process was mainly conducted during the period of Fascist rule between 1922 and 1943.

Alojz Rebula was a Slovene writer, playwright, essayist, and translator, and a prominent member of the Slovene minority in Italy. He lived and worked in Villa Opicina in the Province of Trieste, Italy. He was a member of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Lavo Čermelj, Italianized name Lavo Cermeli, was a Slovene physicist, political activist, journalist, and author. In the 1930s, he was one of the foremost representatives of Slovene anti-Fascist émigrés from the Italian-administered Julian March, together with Josip Vilfan, Ivan Marija Čok, and Engelbert Besednjak.

Marta Verginella is a Slovenian historian from the Slovene minority in Italy in Trieste, notable as one of the most prominent contemporary Slovene historians. Together with Alenka Puhar, she is considered a pioneer in the history of family relations in the Slovene Lands.

Boris Furlan was a Slovenian jurist, philosopher of law, translator and liberal politician. During World War II, he worked as a speaker on Radio London, and was known as "London's Slovene voice". He served as a Minister in the Tito–Šubašić coalition government. In 1947, he was convicted by the Yugoslav Communist authorities at the Nagode Trial.

Engelbert Besednjak was a Slovene Christian Democrat politician, lawyer and journalist. In the 1920s, he was one of the leaders of the Slovene and Croat minority in the Italian-administered Julian March. In the 1930s, he was one of the leaders of Slovene anti-Fascist émigrés from the Slovenian Littoral, together with Josip Vilfan, Ivan Marija Čok and Lavo Čermelj.

Demetrio Volcic, also known in Slovene as Dimitrij Volčič, was an Italian journalist, author, and politician of Slovenian descent. He rose to prominence in the late 1960s and early 1970s as foreign correspondent for the Italian television RAI. In the late 1990s, he served as member of the Italian Senate, and later as Member of European Parliament for the European Socialist Party.

Municipal elections were held in the six municipalities of the Anglo-American occupation zone of the Free Territory of Trieste in June 1949, Trieste, Duino-Aurisina, San Dorligo della Valle, Sgonico, Monrupino and Muggia. There were 197,266 eligible voters in the electoral rolls in Trieste and a combined number of 15,392 eligible voters in the five other municipalities.

The Imperial Free City of Trieste and its Territory was a possession of the Habsburg monarchy in the Holy Roman Empire from the 14th century to 1806, a constituent part of the German Confederation and the Austrian Littoral from 1849 to 1920, and part of the Italian Julian March until 1922. In 1719 it was declared a free port by Emperor Charles VI; the construction of the Austrian Southern Railway (1841–57) turned it into a bustling seaport, through which much of the exports and imports of the Austrian Lands were channelled. The city administration and economy were dominated by the city's Italian population element; Italian was the language of administration and jurisdiction. In the later 19th and early 20th century, the city attracted the immigration of workers from the city's hinterlands, many of whom were speakers of Slovene.

The Slovene minority in Italy (1920–1947) was the indigenous Slovene population—approximately 327,000 out of a total population of 1.3 million ethnic Slovenes at the time—that was cut from the remaining three-quarters of the Slovene ethnic community after the First World War. According to the secret Treaty of London and the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920, the former Austrian Littoral and western part of the former Inner Carniola of defeated Austria-Hungary were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy. Whereas only a few thousand Italians were left in the new South Slavic state, a population of half a million Slavs, both Slovenes and Croats, was subjected to forced Italianization until the fall of Fascism in Italy. After the Second World War, most of the region known as the Slovenian Littoral was transferred to Yugoslavia under the terms of the Treaty of Peace with Italy, 1947.

Milko Bambič also known by the nicknames Cvetanov and Banetov, was a prolific illustrator, cartoonist, caricaturist, inventor, children's writer, publicist, and painter from the Slovene minority in Italy (1920-1947). He is regarded as one of the most versatile Slovene artists and a prominent Italian Futurist painter. He published in both Italian and Slovene. He is known for the first Slovene comic strip Little Negro Bu-ci-bu, an allegory of Mussolini's career, and as the creator of the Three Hearts brand, still used today by Radenska.

Little Negro Bu-ci-bu, also mentioned as Buci-Bu, was the first Slovene comic strip. It was created by Milko Bambič and published in 1927 in the children's column of the monthly Naš glas in Trieste. It is a story about an arrogant and tyrannical black king that with his false wisdom leads his people to ruin and commits suicide. It caused a controversy, because it was seen as a parody on the Italian leader Mussolini, and the author predicted his demise. The Italian Fascist authorities forbade Bambič's works. He escaped from Trieste to Yugoslavia to avoid arrest.

Slovene minority in Italy, also known as Slovenes in Italy is the name given to Italian citizens who belong to the autochthonous Slovene ethnic and linguistic minority living in the Italian autonomous region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. The vast majority of members of the Slovene ethnic minority live in the Provinces of Trieste, Gorizia, and Udine. Estimates of their number vary significantly; the official figures show 52,194 Slovenian speakers in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, as per the 1971 census, but Slovenian estimates speak of 83,000 to 100,000 people.