Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains—particularly in the back—and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In about 15% of people, within a day of improving the fever comes back, abdominal pain occurs, and liver damage begins causing yellow skin. If this occurs, the risk of bleeding and kidney problems is increased.

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne disease caused by dengue virus, prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. It is frequently asymptomatic; if symptoms appear, they typically begin 3 to 14 days after infection. These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin itching and skin rash. Recovery generally takes two to seven days. In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue with bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, blood plasma leakage, and dangerously low blood pressure.

Incubation period is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infectious disease, the incubation period signifies the period taken by the multiplying organism to reach a threshold necessary to produce symptoms in the host.

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. The term arbovirus is a portmanteau word. Tibovirus is sometimes used to more specifically describe viruses transmitted by ticks, a superorder within the arthropods. Arboviruses can affect both animals and plants. In humans, symptoms of arbovirus infection generally occur 3–15 days after exposure to the virus and last three or four days. The most common clinical features of infection are fever, headache, and malaise, but encephalitis and viral hemorrhagic fever may also occur.

The Nariva Swamp is the largest freshwater wetland in Trinidad and Tobago and has been designated a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention. The swamp is located on the east coast of Trinidad, immediately inland from the Manzanilla Bay through Biche and covers over 60 square kilometres (23 mi2). The Nariva Swamp is extremely biodiverse, being home to 45 mammal species, 39 reptile species, 33 fish species, 204 bird species, 19 frog species, 213 insect species and 15 mollusc species. All this contained in just 60 square kilometers.

Oropouche fever is a tropical viral infection which can infect humans. It is transmitted by biting midges and mosquitoes, from a natural reservoir which includes sloths, non-human primates, and birds. The disease is named after the region where it was first discovered and isolated in 1955, by the Oropouche River in Trinidad and Tobago. Oropouche fever is caused by the Oropouche virus (OROV), of the Bunyavirales order of viruses.

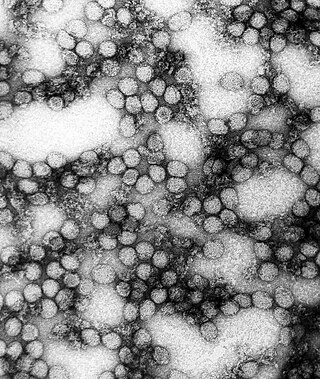

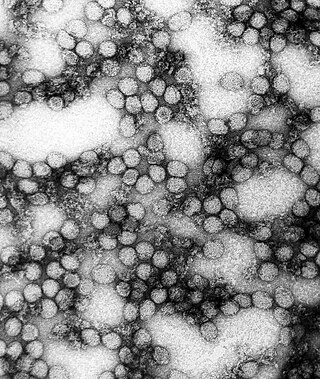

Oropouche orthobunyavirus (OROV) is one of the most common orthobunyaviruses. When OROV infects humans, it causes a rapid fever illness called Oropouche fever. OROV was originally reported in Trinidad and Tobago in 1955 from the blood sample of a fever patient and from a pool of Coquillettidia venezuelensis mosquitoes. In 1960, OROV was isolated from a sloth and a pool of Ochlerotatus serratus mosquitoes in Brazil. The virus is considered a public health threat in tropical and subtropical areas of Central and South America, with over half a million infected people as of 2005. OROV is considered to be an arbovirus due to the method of transmission by the mosquitoes Aedes serratus and Culex quinquefasciatus among sloths, marsupials, primates, and birds.

Wilbur George Downs, was a naturalist, virologist and clinical professor of epidemiology and public health at the Yale School of Medicine and the Yale School of Public Health.

Greenhall's dog-faced bat is a South American bat species of the family Molossidae. It lives in Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, the Guianas, northeastern Brazil and Trinidad.

The National Institute of Virology in Pune, India is an Indian virology research institute and part of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). It was previously known as 'Virus Research Centre' and was founded in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation. It has been designated as a WHO H5 reference laboratory for SE Asia region.

In animals, rabies is a viral zoonotic neuro-invasive disease which causes inflammation in the brain and is usually fatal. Rabies, caused by the rabies virus, primarily infects mammals. In the laboratory it has been found that birds can be infected, as well as cell cultures from birds, reptiles and insects. The brains of animals with rabies deteriorate. As a result, they tend to behave bizarrely and often aggressively, increasing the chances that they will bite another animal or a person and transmit the disease.

Mosquito-borne diseases or mosquito-borne illnesses are diseases caused by bacteria, viruses or parasites transmitted by mosquitoes. Nearly 700 million people contract mosquito-borne illnesses each year, resulting in more than a million deaths.

Haemagogus is a genus of mosquitoes in the dipteran family Culicidae. They mainly occur in Central America and northern South America, although some species inhabit forested areas of Brazil, and range as far as northern Argentina. In the Rio Grande Do Sul area of Brazil, one species, H. leucocelaenus, has been found carrying yellow fever virus. Several species have a distinct metallic sheen.

Zika virus is a member of the virus family Flaviviridae. It is spread by daytime-active Aedes mosquitoes, such as A. aegypti and A. albopictus. Its name comes from the Ziika Forest of Uganda, where the virus was first isolated in 1947. Zika virus shares a genus with the dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile viruses. Since the 1950s, it has been known to occur within a narrow equatorial belt from Africa to Asia. From 2007 to 2016, the virus spread eastward, across the Pacific Ocean to the Americas, leading to the 2015–2016 Zika virus epidemic.

Joseph Lennox Donation Pawan MBE was a Trinidadian bacteriologist who was the first person to show that rabies could be spread by vampire bats to other animals and humans.

Robert Ellis Shope was an American virologist, epidemiologist and public health expert, particularly known for his work on arthropod-borne viruses and emerging infectious diseases. He discovered more novel viruses than any person previously, including members of the Arenavirus, Hantavirus, Lyssavirus and Orbivirus genera of RNA viruses. He researched significant human diseases, including dengue, Lassa fever, Rift Valley fever, yellow fever, viral hemorrhagic fevers and Lyme disease. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of viruses, and curated a global reference collection of over 5,000 viral strains. He was the lead author of a groundbreaking report on the threat posed by emerging infectious diseases, and also advised on climate change and bioterrorism.

John Payne Woodall (1935–2016), known as Jack Woodall, was an American-British entomologist and virologist who made significant contributions to the study of arboviruses in South America, the Caribbean and Africa. He did research on the causative agents of dengue fever, Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever, o'nyong'nyong fever, yellow fever, Zika fever, and others.

Scott Halstead is an American physician-scientist, virologist and epidemiologist known for his work in the fields of tropical medicine and vaccine development. He is considered one of the world's foremost authorities on viruses transmitted by mosquitoes, including Dengue, Japanese encephalitis, chikungunya and Zika. He was one of the first researchers to identify the phenomenon known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), where the antibodies generated from a first dengue infection can sometimes worsen the symptoms from a second infection.

In infectious disease epidemiology, a sporadic disease is an infectious disease which occurs only infrequently, haphazardly, irregularly, or occasionally, from time to time in a few isolated places, with no discernible temporal or spatial pattern, as opposed to a recognizable epidemic outbreak or endemic pattern. The cases are so few and separated so widely in time and place that there exists little or no discernable connection within them. They also do not show a recognizable common source of infection.

An outbreak of Oropouche fever began in December 2023. Over 9,852 infections have been reported, including the first outside the Amazon region to which Oropouche virus is endemic.