The Puebloans or Pueblo peoples, are Native Americans in the Southwestern United States who share common agricultural, material and religious practices. When Spaniards entered the area beginning in the 16th century, they came across complex, multi-story villages built of adobe, stone and other local materials, which they called pueblos, or towns, a term that later came to refer also to the peoples who live in these villages.

This article concerns itself with the Spiritual beliefs of the Cherokee, Native Americans indigenous to the Appalachias, and today are enrolled in the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Cherokee Nation, and United Keetowah Band of Cherokee Indians. Some of these myths go by different names in different branches of the tribe, however, the actual myth remains the same.

The Hopi maintain a complex religious and mythological tradition stretching back over centuries. However, it is difficult to definitively state what all Hopis as a group believe. Like the oral traditions of many other societies, Hopi mythology is not always told consistently and each Hopi mesa, or even each village, may have its own version of a particular story. But, "in essence the variants of the Hopi myth bear marked similarity to one another." It is also not clear that those stories which are told to non-Hopis, such as anthropologists and ethnographers, represent genuine Hopi beliefs or are merely stories told to the curious while keeping safe the Hopi's more sacred doctrines. As folklorist Harold Courlander states, "there is a Hopi reticence about discussing matters that could be considered ritual secrets or religion-oriented traditions." In addition, the Hopis have always been willing to assimilate foreign ideas into their cosmology if they are proven effective for such practical necessities as bringing rain. The Hopi had at least some contact with Europeans as early as the 16th century, and some believe that European Christian traditions may have entered Hopi cosmology at some point. Indeed, Spanish missions were built in several Hopi villages starting in 1629 and were in operation until the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. However, after the revolt, it was the Hopi alone of all the Pueblo tribes who kept the Spanish out of their villages permanently, and regular contact with whites did not begin again until nearly two centuries later. The Hopi mesas have therefore been seen as "relatively unacculturated" at least through the early 20th century, and it may be posited that the European influence on the core themes of Hopi mythology was slight.

Much of the mythology of the Iroquois has been preserved, including creation stories and some folktales. Recorded in wampum as recitations, written down later, the spellings of names differed as transliteration varies and spellings even in European languages were not entirely regularized. Different versions of some stories exist, reflecting different localities and different times. It is possible that the written versions were influenced by Christianity.

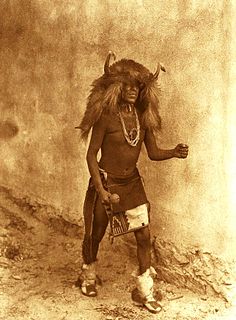

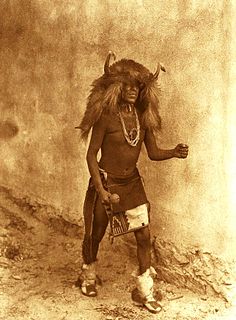

A kachina is a spirit being in the religious beliefs of the Pueblo people, Native American cultures located in the southwestern part of the United States. In the Pueblo culture, kachina rituals are practiced by the Hopi, Zuni, Hopi-Tewa and certain Keresan Tribes, as well as in most Pueblo Tribes in New Mexico. The kachina concept has three different aspects: the supernatural being, the kachina dancers, and kachina dolls, small dolls carved in the likeness of the kachina, that are given only to those who are, or will be responsible for the respectful care and well-being of the doll, such as a mother, wife, or sister.

Diné Bahaneʼ, the Navajo creation myth, describes the prehistoric emergence of the Navajo, and centers on the area known as the Dinétah, the traditional homeland of the Navajo. This story forms the basis for the traditional Navajo way of life. The basic outline of Diné Bahaneʼ begins with the Niłchʼi Diyin being created, the mists of lights which arose through the darkness to animate and bring purpose to the four Diyin Dineʼé, supernatural and sacred in the different three lower worlds. All these things were spiritually created in the time before the Earth existed and the physical aspect of humans did not exist yet, but the spiritual did.

Kewa Pueblo, formerly known as Santo Domingo Pueblo, is a census-designated place (CDP) in Sandoval County, New Mexico, United States and a federally recognized tribe of Native American Pueblo people.

Juan de Oñate y Salazar was a conquistador from New Spain, explorer, and colonial governor of the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México in the viceroyalty of New Spain. He led early Spanish expeditions to the Great Plains and Lower Colorado River Valley, encountering numerous indigenous tribes in their homelands there. Oñate founded settlements in the province, now in the Southwestern United States.

The Zuni are Native American Pueblo peoples native to the Zuni River valley. The current day Zuni are a Federally recognized tribe and most live in the Pueblo of Zuni on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, in western New Mexico, United States. The Pueblo of Zuni is 55 km (34 mi) south of Gallup, New Mexico. The Zuni tribe lived in multi level adobe houses. In addition to the reservation, the tribe owns trust lands in Catron County, New Mexico, and Apache County, Arizona. The Zuni call their homeland Halona Idiwan’a or Middle Place.

Leslie Marmon Silko is a Laguna Pueblo writer and one of the key figures in the First Wave of what literary critic Kenneth Lincoln has called the Native American Renaissance.

A Tjurunga or as it is sometimes spelled, Churinga, is an object considered to be of religious significance by Central Australian indigenous people of the Arrernte groups. Tjurunga often had a wide and indeterminate native significance. They may be used variously in sacred ceremonies, as bullroarers, in sacred ground paintings, in ceremonial poles, in ceremonial headgear, in sacred chants and in sacred earth mounds.

The Zia or Tsʾíiyʾamʾé are an indigenous tribe centered at Zia Pueblo (Tsi'ya), an Indian reservation in the U.S. state of New Mexico. The Zia are known for their pottery and use of the sun symbol. They are one of the Keres Pueblo peoples and speak the Eastern Keres language.

The Navajos are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States. The Navajo people are politically divided between two federally recognized tribes, the Navajo Nation and the Colorado River Indian Tribes.

Pueblo of Isleta or Isleta Pueblo is an unincorporated community Tanoan pueblo in Bernalillo County, New Mexico, United States, originally established around the 14th century. The native name of the pueblo is Shiewhibak (Shee-eh-whíb-bak) meaning "a knife laid on the ground to play whib", a native footrace. Its people are federally recognized as a Native American tribe.

Lucy Martin Lewis was a Native American potter from Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico. She is known for her black-on-white decorative ceramics made using traditional techniques.

The Pueblo clowns are jesters or tricksters in the Kachina religion. It is a generic term, as there are a number of these figures in the ritual practice of the Pueblo people. Each has a unique role; belonging to separate Kivas and each has a name that differs from one mesa or pueblo to another.

Simon J. Ortiz is a Puebloan writer of the Acoma Pueblo tribe, and one of the key figures in the second wave of what has been called the Native American Renaissance. He is one of the most respected and widely read Native American poets. Ortiz's commitment to preserving and expanding the literary and oral traditions of the Acoma accounts for many of the themes and techniques that compose his work. Ortiz identifies himself less as a "poet" than a "storyteller". The composition of a traditional Pueblo storyteller includes not only oral narrative materials, which adapt easily to short story or essay forms, but also songs, chants, winter stories, sacred oral narratives associated with origin stories and their attendant ceremonies. Such materials when recited aloud, have a distinctly "poetic" texture.

Ceremony is a novel by Native American writer Leslie Marmon Silko, first published by Penguin in March 1977. The title Ceremony is based upon the oral traditions and ceremonial practices of the Navajo and Pueblo people.