Related Research Articles

Northern Ireland is a part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland that is variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares an open border to the south and west with the Republic of Ireland. At the 2021 census, its population was 1,903,175, making up around 3% of the UK's population and 27% of the population on the island of Ireland. The Northern Ireland Assembly, established by the Northern Ireland Act 1998, holds responsibility for a range of devolved policy matters, while other areas are reserved for the UK Government. The government of Northern Ireland cooperates with the government of Ireland in several areas under the terms of the Belfast Agreement. The Republic of Ireland also has a consultative role on non-devolved governmental matters through the British–Irish Governmental Conference (BIIG).

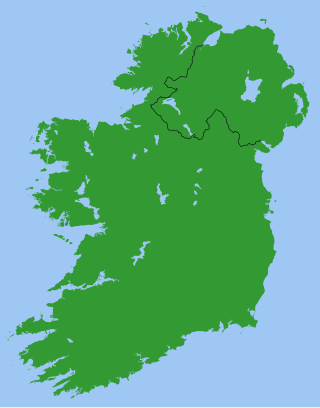

Southern Ireland was the larger of the two parts of Ireland that were created when Ireland was partitioned by the Government of Ireland Act 1920. It comprised 26 of the 32 counties of Ireland or about five-sixths of the area of the island, whilst the remaining six counties, which occupied most of Ulster in the north of the island, formed Northern Ireland. Southern Ireland included County Donegal, despite it being the largest county in Ulster and the most northerly county in all of Ireland.

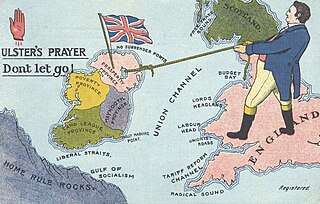

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Protestant minority, unionism mobilised in the decades following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to oppose restoration of a separate Irish parliament. Since Partition in 1921, as Ulster unionism its goal has been to retain Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom and to resist the prospect of an all-Ireland republic. Within the framework of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which concluded three decades of political violence, unionists have shared office with Irish nationalists in a reformed Northern Ireland Assembly. As of February 2024, they no longer do so as the larger faction: they serve in an executive with an Irish republican First Minister.

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cultural nationalism based on the principles of national self-determination and popular sovereignty. Irish nationalists during the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries such as the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, the Fenian Brotherhood during the 1880s, Fianna Fáil in the 1920s, and Sinn Féin styled themselves in various ways after French left-wing radicalism and republicanism. Irish nationalism celebrates the culture of Ireland, especially the Irish language, literature, music, and sports. It grew more potent during the period in which all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, which led to most of the island gaining independence from the UK in 1922.

The British-Irish Agreement was a 1985 treaty between the United Kingdom of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, shortly Britain, and the Republic of Ireland, shortly Ireland, which aimed to help bring an end to the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The treaty gave the Irish government an advisory role in Northern Ireland's government while confirming that there would be no change in the constitutional position of Northern Ireland unless a majority of its citizens agreed to join the state of Ireland. It also set out conditions for the establishment of a devolved consensus government in the region.

The Ulster Special Constabulary was a quasi-military reserve special constable police force in what would later become Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the partition of Ireland. The USC was an armed corps, organised partially on military lines and called out in times of emergency, such as war or insurgency. It performed this role most notably in the early 1920s during the Irish War of Independence and the 1956–1962 IRA Border Campaign.

Irish republicanism is the political movement for an Irish republic, void of any British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously elective and militant and has been both widely supported and iconoclastic.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) (Irish: Cumann Cearta Sibhialta Thuaisceart Éireann) was an organisation that campaigned for civil rights in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Formed in Belfast on 9 April 1967, the civil rights campaign attempted to achieve reform by publicising, documenting, and lobbying for an end to discrimination against Catholics in areas such as elections (which were subject to gerrymandering and property requirements), discrimination in employment, in public housing and abuses of the Special Powers Act.

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a united Ireland independent of the UK. Unlike other strands of unionism, loyalism has been described as an ethnic nationalism of Ulster Protestants and "a variation of British nationalism". Loyalists are often said to have a conditional loyalty to the British state so long as it defends their interests. They see themselves as loyal primarily to the Protestant British monarchy rather than to British governments and institutions, while Garret FitzGerald argued they are loyal to 'Ulster' over 'the Union'. A small minority of loyalists have called for an independent Ulster Protestant state, believing they cannot rely on British governments to support them. The term 'loyalism' is usually associated with paramilitarism.

The Socialist Party of Ireland (SPI) was a minor left-wing political party which existed in Ireland from 1971 to 1982.

The Partition of Ireland was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. It was enacted on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The Act intended both territories to remain within the United Kingdom and contained provisions for their eventual reunification. The smaller Northern Ireland was duly created with a devolved government and remained part of the UK. The larger Southern Ireland was not recognised by most of its citizens, who instead recognised the self-declared 32-county Irish Republic. On 6 December 1922, Ireland was partitioned. At that time, the territory of Southern Ireland left the UK and became the Irish Free State, now known as the Republic of Ireland. Ireland had a large Catholic, nationalist majority who wanted self-governance or independence. Prior to partition the Irish Home Rule movement compelled the British Parliament to introduce bills that would give Ireland a devolved government within the UK. This led to the Home Rule Crisis (1912–14), when Ulster unionists/loyalists founded a large paramilitary organization, the Ulster Volunteers, that could be used to prevent Ulster from being ruled by an Irish government. The British government proposed to exclude all or part of Ulster, but the crisis was interrupted by the First World War (1914–18). Support for Irish independence grew during the war and after the 1916 armed rebellion known as the Easter Rising.

The All-for-Ireland League (AFIL) was an Irish, Munster-based political party (1909–1918). Founded by William O'Brien MP, it generated a new national movement to achieve agreement between the different parties concerned on the historically difficult aim of Home Rule for the whole of Ireland. The AFIL established itself as a separate non-sectarian party in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, binding a group of independent nationalists MPs to pursue a broader concept of Irish nationalism, a consensus of political brotherhood and reconciliation among all Irishmen, primarily to win Unionist consent to an All-Ireland parliamentary settlement.

The repartition of Ireland has been suggested as a possible solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland. In 1922 Ireland was partitioned on county lines, and left Northern Ireland with a mixture of both unionists, who wish to remain in the United Kingdom, and nationalists, who wish to join a United Ireland. As the two communities are somewhat regionalised, redrawing the border to better divide the two groups was considered at various points throughout the 20th century.

The British and Irish Communist Organisation (B&ICO) was a small group based in London, Belfast, Cork, and Dublin. Its leader was Brendan Clifford. The group produced a number of pamphlets and regular publications, including The Irish Communist and Workers Weekly in Belfast. Τhe group currently expresses itself through Athol Books with its premier publication being the Irish Political Review. The group also continues to publish Church & State, Irish Foreign Affairs, Labour Affairs and Problems.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Troubles.

Desmond Carolan Fennell was an Irish writer, essayist, cultural philosopher, and linguist. Throughout his career, Fennell repeatedly departed from prevailing norms. In the 1950s and early 1960s, with his extensive foreign travel and reporting and his travel book, Mainly in Wonder, he departed from the norm of Irish Catholic writing at the time. From the late 1960s into the 1970s, in developing new approaches to the partition of Ireland and the Irish language revival, he deviated from political and linguistic Irish nationalism, and with the philosophical scope of his Beyond Nationalism: The Struggle against Provinciality in the Modern World, from contemporary Irish culture generally.

William McMullen was an Irish trade unionist and politician. A member of the Labour movement, McMullen primary work was a trade unionist, but he was also a successful politician who secured office in the Parliament of Northern Ireland. Despite coming from a Presbyterian family, McMullen was also an avowed Irish republican, bitterly opposing the partition of Ireland in the 1920s and joining the Republican Congress in the 1930s. In the 1940s McMullen became the leader of the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union and in the 1950s, he became a member of the Irish senate.

Arthur Edward Clery was an Irish republican politician and university professor.

Since 1998, Northern Ireland has devolved government within the United Kingdom. The government and Parliament of the United Kingdom are responsible for reserved and excepted matters. Reserved matters are a list of policy areas, which the Westminster Parliament may devolve to the Northern Ireland Assembly at some time in future. Excepted matters are never expected to be considered for devolution. On all other matters, the Northern Ireland Executive together with the 90-member Northern Ireland Assembly may legislate and govern for Northern Ireland. Additionally, devolution in Northern Ireland is dependent upon participation by members of the Northern Ireland Executive in the North/South Ministerial Council, which co-ordinates areas of co-operation between Northern Ireland and the Ireland.

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1912.

References

- 1 2 Where is the Irish Border? Theories of Division in Ireland, by Sean Swan, Nordic Ireland Studies, 2005, pp. 61–87.

- ↑ Lee, J. J. (1989). Ireland, 1912–1985: Politics and Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Kissane, Bill (2005). The Politics of the Irish Civil War. Oxford University Press. p. 50.

- ↑ ""Two-Nation Theory" Absurd Idea", Irish Times, 11 November 1960, pp. 1, 5 (report of a debate on Partition in Dáil Éireann).

- ↑ See Gageby's essay in Conor Cruise O'Brien Introduces Ireland by Owen Dudley Edwards and Conor Cruise O'Brien, Deutsch, 1969

- ↑ Ideology and the Irish Question: Ulster Unionism and Irish Nationalism 1912–1916 by Paul Bew, OUP, 1998.

- ↑ The Idea of a Nation, reprinted 2002 by University College Dublin Press; edited by Patrick Maume

- ↑ The Irish border as a cultural divide: a contribution to the study of regionalism in the British Isles. (2nd. Edition) M W Heslinga, Assen (in the Netherlands), Van Gorcum, 1979.

- ↑ "Mapping the Narrow Ground: Geography, History and Partition" by Mary Burgess, Field Day Review, Vol. 1, (2005), pp. 121–132 (a discussion of Heslinga's ideas on Northern Ireland).

- ↑ See, for instance, The Two Irish Nations: A Reply to Michael Farrell by the British and Irish Communist Organisation, Athol Books, 1971.

- ↑ Austen Morgan and Bob Purdie, Ireland: Divided Nation, Divided Class, Ink Links, 1980.

- ↑ John A. Murphy discusses Kemmy's Two-Nation Theory in Seanad Éireann, 1981. "Seanad Éireann – Volume 96 – 09 October, 1981 – Constitutional and Legislative Review: Motion (Resumed)". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ↑ For instance, see Fennell's article Some New "Invisibles" for Old? in the Irish Times, 16 April 1973.

- ↑ Desmond Fennell, Heresy: the Battle of Ideas in Modern Ireland, Blackstaff, 1993, pp. 107–8.

- ↑ See, for instance, The Irish Question: Two Centuries of Conflict by John McCaffery, 1995, p. 210, and A History of the Irish Working Class, by Peter Berresford Ellis, 1985, p. 329

- ↑ Irish Times, 25 October 1971.

- ↑ "Ireland has never been one nation. I support the Two-Nations Theory". Interview with Vanguard member, quoted in Ulster's uncertain defenders : protestant political, paramilitary and community groups and the Northern Ireland conflict by Sarah Nelson. (p.110-111). Belfast, Appletree Press 1984. ISBN 0-904651-98-3

- ↑ Miller, David W. (1978). Queen's Rebels: Ulster Loyalism in historical perspective. Gill and Macmillan.

- ↑ "Self-Determination and the British-Irish", Weekly Worker, 16 February 2006.

- ↑ "Two Nations Once Again". Socialist Democracy . 3 March 2006.