A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable by the state. While criminal law aims to punish individuals who commit crimes, tort law aims to compensate individuals who suffer harm as a result of the actions of others. Some wrongful acts, such as assault and battery, can result in both a civil lawsuit and a criminal prosecution in countries where the civil and criminal legal systems are separate. Tort law may also be contrasted with contract law, which provides civil remedies after breach of a duty that arises from a contract. Obligations in both tort and criminal law are more fundamental and are imposed regardless of whether the parties have a contract.

Trespass is an area of tort law broadly divided into three groups: trespass to the person, trespass to chattels, and trespass to land.

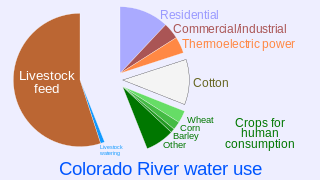

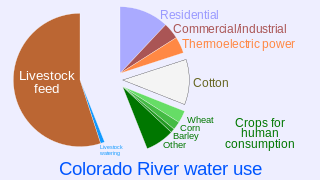

Water resources law is the field of law dealing with the ownership, control, and use of water as a resource. It is most closely related to property law, and is distinct from laws governing water quality.

Riparian water rights is a system for allocating water among those who possess land along its path. It has its origins in English common law. Riparian water rights exist in many jurisdictions with a common law heritage, such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and states in the eastern United States.

Water right in water law is the right of a user to use water from a water source, e.g., a river, stream, pond or source of groundwater. In areas with plentiful water and few users, such systems are generally not complicated or contentious. In other areas, especially arid areas where irrigation is practiced, such systems are often the source of conflict, both legal and physical. Some systems treat surface water and ground water in the same manner, while others use different principles for each.

Rylands v Fletcher (1868) LR 3 HL 330 is a leading decision by the House of Lords which established a new area of English tort law. It established the rule that one's non-natural use of their land, which leads to another's land being damaged as a result of dangerous things emanating from the land, is strictly liable.

Trespass to land is a common law tort or crime that is committed when an individual or the object of an individual intentionally enters the land of another without a lawful excuse. Trespass to land is actionable per se. Thus, the party whose land is entered upon may sue even if no actual harm is done. In some jurisdictions, this rule may also apply to entry upon public land having restricted access. A court may order payment of damages or an injunction to remedy the tort.

The Edwards Aquifer is one of the most prolific artesian aquifers in the world. Located on the eastern edge of the Edwards Plateau in the U.S. state of Texas, it is the source of drinking water for two million people, and is the primary water supply for agriculture and industry in the aquifer's region. Additionally, the Edwards Aquifer feeds the Comal and San Marcos Springs, provides springflow for recreational and downstream uses in the Nueces, San Antonio, Guadalupe, and San Marcos river basins, and is home to several unique and endangered species.

In United States law, the term color of law denotes the "mere semblance of legal right," the "pretense or appearance of" right; hence, an action done under color of law adjusts (colors) the law to the circumstance, yet said apparently legal action contravenes the law.

Lateral and subjacent support, in the law of property, describes the right a landowner has to have that land physically supported in its natural state by both adjoining land and underground structures. If a neighbor's excavation or excessive extraction of underground liquid deposits causes subsidence, such as by causing the landowner's land to cave in, the neighbor will be subject to strict liability in a tort action. The neighbor will also be strictly liable for damage to buildings on the landowner's property if the landowner can show that the weight of the buildings did not contribute to the collapse of the land. If the landowner is unable to make such a showing, the neighbor must be shown to have been negligent in order for the landowner to recover damages.

The rule of capture or law of capture, part of English common law and adopted by a number of U.S. states, establishes a rule of non-liability for captured natural resources including groundwater, oil, gas, and game animals. The general rule is that the first person to "capture" such a resource owns that resource. For example, landowners who extract or “capture” groundwater, oil, or gas from a well that bottoms within the subsurface of their land acquire absolute ownership of the substance even if it is drained from the subsurface of another’s land. The landowner who captures the substance owes no duty of care to other landowners. For example, a water well owner may dry up wells owned by adjacent landowners without fear of liability unless the groundwater was withdrawn for malicious purposes, the groundwater was not put to a beneficial use without waste, or "such conduct is a proximate cause of the subsidence of the land of others." A corollary of that rule is that a person who drills for groundwater, oil, or gas may not extract the substance from a well that bottoms within the subsurface estate of another by drilling on a slant.

Oil and gas law in the United States is the branch of law that pertains to the acquisition and ownership rights in oil and gas both under the soil before discovery and after its capture, and adjudication regarding those rights.

Drainage law is a specific area of water law related to drainage of surface water on real property. It is particularly important in areas where freshwater is scarce, flooding is common, or water is in high demand for agricultural or commercial purposes.

The correlative rights doctrine is a legal doctrine limiting the rights of landowners to a common source of groundwater to a reasonable share, typically based on the amount of land owned by each on the surface above. This doctrine is also applied to oil and gas in some U.S. states.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and introduction to tort law in common law jurisdictions:

Cline v. American Aggregates Corporation, 474 N.E.2d 324, was a case decided by the Supreme Court of Ohio that first applied the reasonable use doctrine to water use in that state.

Water law in the United States refers to the Water resources law laws regulating water as a resource in the United States. Beyond issues common to all jurisdictions attempting to regulate water's uses, water law in the United States must contend with:

Groundwater banking is a water management mechanism designed to increase water supply reliability. Groundwater can be created by using dewatered aquifer space to store water during the years when there is abundant rainfall. It can then be pumped and used during years that do not have a surplus of water. People can manage the use of groundwater to benefit society through the purchasing and selling of these groundwater rights. The surface water should be used first, and then the groundwater will be used when there is not enough surface water to meet demand. The groundwater will reduce the risk of relying on surface water and will maximize expected income. There are regulatory storage-type aquifer recovery and storage systems which when water is injected into it gives the right to withdraw the water later on. Groundwater banking has been implemented into semi-arid and arid southwestern United States because this is where there is the most need for extra water. The overall goal is to transfer water from low-value to high-value uses by bringing buyers and sellers together.

Water in Arkansas is an important issue encompassing the conservation, protection, management, distribution and use of the water resource in the state. Arkansas contains a mixture of groundwater and surface water, with a variety of state and federal agencies responsible for the regulation of the water resource. In accordance with agency rules, state, and federal law, the state's water treatment facilities utilize engineering, chemistry, science and technology to treat raw water from the environment to potable water standards and distribute it through water mains to homes, farms, business and industrial customers. Following use, wastewater is collected in collection and conveyance systems, decentralized sewer systems or septic tanks and treated in accordance with regulations at publicly owned treatment works (POTWs) before being discharged to the environment.

Edwards Aquifer Authority v. Day and McDaniel is a judgment of the Supreme Court of Texas.