In law, possession is the control a person intentionally exercises toward a thing. Like ownership, the possession of anything is commonly regulated by country under property law. In all cases, to possess something, a person must have an intention to possess it. A person may be in possession of some property.

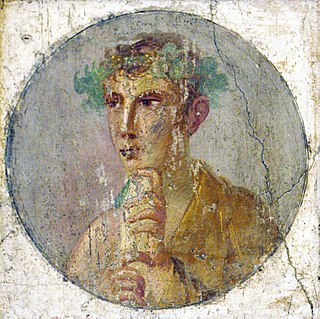

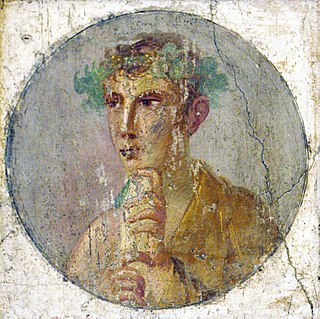

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables, to the Corpus Juris Civilis ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I. Roman law forms the basic framework for civil law, the most widely used legal system today, and the terms are sometimes used synonymously. The historical importance of Roman law is reflected by the continued use of Latin legal terminology in many legal systems influenced by it, including common law.

In property law, title is an intangible construct representing a bundle of rights in (to) a piece of property in which a party may own either a legal interest or equitable interest. The rights in the bundle may be separated and held by different parties. It may also refer to a formal document, such as a deed, that serves as evidence of ownership. Conveyance of the document may be required in order to transfer ownership in the property to another person. Title is distinct from possession, a right that often accompanies ownership but is not necessarily sufficient to prove it. In many cases, possession and title may each be transferred independently of the other. For real property, land registration and recording provide public notice of ownership information.

Adverse possession, sometimes colloquially described as "squatter's rights", is a legal principle in common law under which a person who does not have legal title to a piece of property—usually land —may acquire legal ownership based on continuous possession or occupation of the property without the permission (licence) of its legal owner.

Usucaption, also known as acquisitive prescription, is a concept found in civil law systems and has its origin in the Roman law of property.

Accession has different definitions depending upon its application.

Uti possidetis is an expression that originated in Roman private law, where it was the name of a procedure about possession of land. Later, by a misleading analogy, it was transferred to international law, where it has had more than one meaning, all concerning sovereign right to territory.

In Roman law, status describes a person's legal status. The individual could be a Roman citizen, unlike foreigners; or he could be free, unlike slaves; or he could have a certain position in a Roman family either as head of the family, or as a lower member.

Specificatio is a legal concept adopted from Roman law. It is an original mode of acquisition, since it involves deriving rights over objects that are not subject to pre-existing rights of ownership.

Conversion is an intentional tort consisting of "taking with the intent of exercising over the chattel an ownership inconsistent with the real owner's right of possession". In England and Wales, it is a tort of strict liability. Its equivalents in criminal law include larceny or theft and criminal conversion. In those jurisdictions that recognise it, criminal conversion is a lesser crime than theft/larceny.

Scots property law governs the rules relating to property found in the legal jurisdiction of Scotland. As a hybrid legal system with both common law and civil law heritage, Scots property law is similar, but not identical, to property law in South Africa and the American state of Louisiana.

Rapina was a delict of Roman law.

Tracing is a procedure in English law used to identify property which has been taken from the claimant involuntarily or which the claimant wishes to recover. It is not in itself a way to recover the property, but rather to identify it so that the courts can decide what remedy to apply. The procedure is used in several situations, broadly demarcated by whether the property has been transferred because of theft, breach of trust, or mistake.

South African property law regulates the "rights of people in or over certain objects or things." It is concerned, in other words, with a person's ability to undertake certain actions with certain kinds of objects in accordance with South African law. Among the formal functions of South African property law is the harmonisation of individual interests in property, the guarantee and protection of individual rights with respect to property, and the control of proprietary management relationships between persons, as well as their rights and obligations. The protective clause for property rights in the Constitution of South Africa stipulates those proprietary relationships which qualify for constitutional protection. The most important social function of property law in South Africa is to manage the competing interests of those who acquire property rights and interests. In recent times, restrictions on the use of and trade in private property have been on the rise.

Furtum was a delict of Roman law comparable to the modern offence of theft despite being a civil and not criminal wrong. In the classical law and later, it denoted the contrectatio ("handling") of most types of property with a particular sort of intention – fraud and in the later law, a view to gain. It is unclear whether a view to gain was always required or added later, and, if the latter, when. This meant that the owner did not consent, although Justinian broadened this in at least one case. The law of furtum protected a variety of property interests, but not land, things without an owner, or types of state or religious things. An owner could commit theft by taking his things back in certain circumstances, as could a borrower or similar user through misuse.

In Roman law, contracts could be divided between those in re, those that were consensual, and those that were innominate contracts in Roman law. Although Gaius only identifies a single type of contract in re, it is commonly thought that there were four types of these, as Justinian identifies: mutuum, commodatum, depositum (deposit) and pignus (pledge).

Property lawin the United States is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property and personal property, including intangible property such as intellectual property. Property refers to legally protected claims to resources, such as land and personal property. Property can be exchanged through contract law, and if property is violated, one could sue under tort law to protect it.

Possession in Scots law occurs when an individual physically holds property with the intent to use it. Possession is traditionally viewed as a state of fact, rather than real right and is not the same concept as ownership in Scots law. It is now said that certain possessors may additionally have the separate real right of ius possidendi. Like much of Scots property law, the principles of the law of possession mainly derive from Roman law.

In Roman law, obligatio ex delicto is an obligation created as a result of a delict. While "delict" itself was never defined by Roman jurisprudents, delicts were generally composed of injurious or otherwise illicit actions, ranging from those covered by criminal law today such as theft (furtum) and robbery (rapina) to those usually settled in civil disputes in modern times such as defamation, a form of iniuria. Obligationes ex delicto therefore can be characterized as a form of private punishment, but also as a form of loss compensation.

In Roman law, the praedial servitude or property easement, or simply servitude (servitutes), consists of a real right the owners of neighboring lands can establish voluntarily, in order that a property called servient lends to other called dominant the permanent advantage of a limited use. As use relations, servitudes are fundamentally solidary and indivisible rights, the latter being what causes the servitude to remain intact despite the fact that any property involved may be divided. Furthermore, there is no possibility of acquisition or partial extinction.