Related Research Articles

Wends is a historical name for Slavs who inhabited present-day northeast Germany. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various people, tribes or groups depending on where and when it was used. In the modern day, communities identifying as Wendish exist in Slovenia, Austria, Lusatia, the United States, and Australia.

Istria is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at the top of the Adriatic between the Gulf of Trieste and the Kvarner Gulf, the peninsula is shared by three countries: Croatia, Slovenia, and Italy, 90% of its area being part of Croatia. Most of Croatian Istria is part of Istria County.

Carantania, also known as Carentania, was a Slavic principality that emerged in the second half of the 7th century, in the territory of present-day southern Austria and north-eastern Slovenia. It was the predecessor of the March of Carinthia, created within the Carolingian Empire in 889.

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians, are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovene as their native language. According to ethnic classification based on language, they are closely related to other South Slavic ethnic groups, as well as more distantly to West Slavs.

The Vistula Veneti, also called Baltic Veneti or Venedi, were an Indo-European people that inhabited the lands of central Europe east of the Vistula River and the Bay of Gdańsk. Ancient Roman geographers first mentioned Venedi in the 1st century AD, differentiating a group of peoples whose manner and language differed from those of the neighbouring Germanic and Sarmatian tribes. In the 6th century AD, Byzantine historians described the Veneti as the ancestors of the Slavs who, during the second phase of the Migration Period, crossed the northern frontiers of the Byzantine Empire.

"Naprej, zastava slave" or "Naprej, zastava Slave" is a former national anthem of Slovenia, used from 1860 to 1989. It is now used as the official service song of the Slovenian Armed Forces and as the anthem of the Slovenian nation.

Carantanians were a Slavic people of the Early Middle Ages, living in the principality of Carantania, later known as Carinthia, which covered present-day southern Austria and parts of Slovenia. They are considered ancestors of modern Slovenes, particularly Carinthian Slovenes.

Venetic is an extinct Indo-European language, most commonly classified into the Italic subgroup, that was spoken by the Veneti people in ancient times in northeast Italy and part of modern Slovenia, between the Po Delta and the southern fringe of the Alps, associated with the Este culture.

Carinthian Slovenes or Carinthian Slovenians are the indigenous minority of Slovene ethnicity, living within borders of the Austrian state of Carinthia, neighboring Slovenia. Their status of the minority group is guaranteed in principle by the Constitution of Austria and under international law, and have seats in the National Ethnic Groups Advisory Council.

The Windic March was a medieval frontier march of the Holy Roman Empire, roughly corresponding to the Lower Carniola region in present-day Slovenia. In Slovenian historiography, it is known as the Slovene March.

The black panther, also known as the Carantanian panther after the Medieval principality of Carantania, is a Carinthian historical symbol, which represents a stylized heraldic panther. As a heraldic symbol, it appeared on the coat of arms of the Carinthian Duke Herman II as well as of the Styrian Margrave Ottokar III. In this region it was most frequently imaged on various monuments and tombstones. The symbol can still be found in the coat of arms of the Austrian state of Styria, although in a white version on green background, dating back to the 13th century. The symbol is also widely used within structures of the Slovenian security forces; namely by the Slovenian Armed Forces and the Slovenian Police. Since 1991, there have been several proposals to replace the Slovenian coat of arms with the black panther.

Vojnomir, Voynomir or Vonomir I was a Slavic military commander in Frankish service, the duke of Slavs in Lower Pannonia, who ruled from c. 790 to c. 800 or from 791 to c. 810 over an area that corresponds to modern-day Slavonia, Croatia.

The Slovene lands or Slovenian lands is the historical denomination for the territories in Central and Southern Europe where people primarily spoke Slovene. The Slovene lands were part of the Illyrian provinces, the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary. They encompassed Carniola, southern part of Carinthia, southern part of Styria, Istria, Gorizia and Gradisca, Trieste, and Prekmurje. Their territory more or less corresponds to modern Slovenia and the adjacent territories in Italy, Austria, Hungary, and Croatia, where autochthonous Slovene minorities live. The areas surrounding present-day Slovenia were never homogeneously ethnically Slovene.

The settlement of the Eastern Alps region by early Slavs took place during the 6th to 8th centuries CE. It formed part of the southward expansion of early Slavs which would result in the South Slavic group, and would ultimately result in the ethnogenesis of present-day Slovenes. The Eastern Alpine territories concerned comprise modern-day Slovenia, Eastern Friuli, in modern-day northeast Italy, and large parts of modern-day Austria.

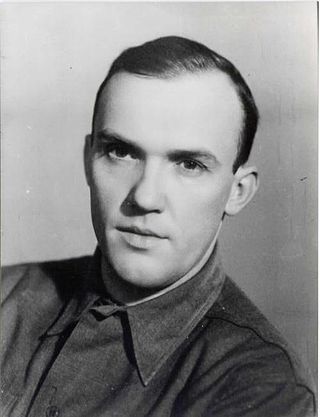

Matej Bor was the pen name of Vladimir Pavšič, who was a Slovene poet, translator, playwright, journalist and Partisan.

Simon Rutar was a Slovene historian and geographer. He wrote primarily on the history and geography of the areas that are now part of the Slovenian Littoral, the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia and the Croatian counties of Istria and Primorsko-Goranska.

Davorin Trstenjak was a Slovene writer, historian and Roman Catholic priest.

Jožko Šavli was a Slovene author, self-declared historian and high school teacher in economic sciences from Italy.

Bogo Grafenauer was a Slovenian historian, who mostly wrote about medieval history in the Slovene Lands. Together with Milko Kos, Fran Zwitter, and Vasilij Melik, he was one of the founders of the so-called Ljubljana school of historiography.

Slavia Friulana, which means Friulian Slavia, is a small mountainous region in northeastern Italy and it is so called because of its Slavic population which settled here in the 8th century AD. The territory is located in the Italian region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, between the town of Cividale del Friuli and the Slovenian border.

References

- 1 2 Lencek, Rado (1990). "The Linguistic Premises of Matej Bor's Slovene-Venetic Theory". Slovene Studies . 12 (1): 75–86.

- 1 2 Priestly, Tom (1997). "Vandals, Veneti, Windischer: The Pitfalls of Amateur Historical Linguistics". Slovene Studies . 12 (1/2): 3–41.

- ↑ Priestly, Tom (2001). "Vandali, Veneti, Vindišarji: pasti amaterske historične lingvistike" [Vandals, Veneti, Vindishars: pitfalls of amateur historical linguistics]. Slavistična revija (in Slovenian). 49: 275–303.

- 1 2 Skrbiš, Zlatko (2008). "'The First Europeans' Fantasy of Slovenian Venetologists". In Svašek, Maruška (ed.). Postsocialism: Politics and Emotion in Central and Eastern Europe. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 138–158.

- ↑ Gyllenberg-Orešnik, Birgitta; Piškur, Milena (May 4, 1969). "Se enkrat o skandinavskem izvoru Slovencev". Primorski dnevnik. No. 103. p. 3. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Sonderegger, Stefan (1979). Grundzüge deutscher Sprachgeschichte. Diachronie des Sprachsystems. Band I: Einführung – Genealogie – Konstanten [Basics of German language history. Diachrony of the language system. Volume I: Introduction - Genealogy - Constants] (in German). Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-11-084200-5.

- ↑ Plut-Pregelj, Leopoldina; Rogel, Carole (2010). The A to Z of Slovenia. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. p. 481.