Related Research Articles

A wife is a woman in a marital relationship. A woman who has separated from her partner continues to be a wife until their marriage is legally dissolved with a divorce judgment; or until death, depending on the kind of marriage. On the death of her partner, a wife is referred to as a widow. The rights and obligations of a wife to her partner and her status in the community and law vary between cultures and have varied over time.

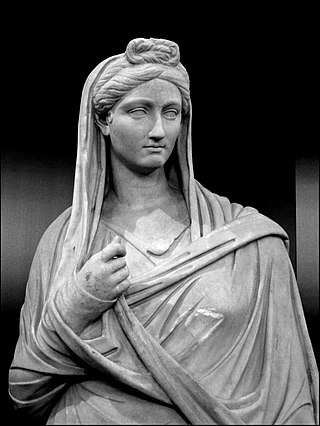

Freeborn women in ancient Rome were citizens (cives), but could not vote or hold political office. Because of their limited public role, women are named less frequently than men by Roman historians. But while Roman women held no direct political power, those from wealthy or powerful families could and did exert influence through private negotiations. Exceptional women who left an undeniable mark on history include Lucretia and Claudia Quinta, whose stories took on mythic significance; fierce Republican-era women such as Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, and Fulvia, who commanded an army and issued coins bearing her image; women of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, most prominently Livia and Agrippina the Younger, who contributed to the formation of Imperial mores; and the empress Helena, a driving force in promoting Christianity.

Adoption in ancient Rome was primarily a legal procedure for transferring paternal power (potestas) to ensure succession in the male line within Roman patriarchal society. The Latin word adoptio refers broadly to "adoption", which was of two kinds: the transferral of potestas over a free person from one head of household to another; and adrogatio, when the adoptee had been acting sui iuris as a legal adult but assumed the status of unemancipated son for purposes of inheritance. Adoptio was a longstanding part of Roman family law pertaining to paternal responsibilities such as perpetuating the value of the family estate and ancestral rites (sacra), which were concerns of the Roman property-owning classes and cultural elite. During the Principate, adoption became a way to ensure imperial succession.

The legal rights of women refers to the social and human rights of women. One of the first women's rights declarations was the Declaration of Sentiments. The dependent position of women in early law is proved by the evidence of most ancient systems.

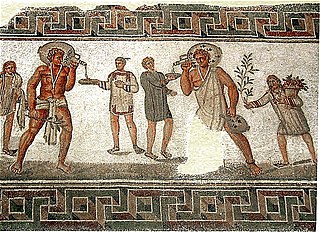

The study of the economies of the ancient city-state of Rome and its empire during the Republican and Imperial periods remains highly speculative. There are no surviving records of business and government accounts, such as detailed reports of tax revenues, and few literary sources regarding economic activity. Instead, the study of this ancient economy is today mainly based on the surviving archeological and literary evidence that allow researchers to form conjectures based on comparisons with other more recent pre-industrial economies.

In the United Kingdom, inheritance tax is a transfer tax. It was introduced with effect from 18 March 1986, replacing capital transfer tax. The UK has the fourth highest inheritance tax rate in the world, according to conservative think tank, the Tax Foundation, though only a very small proportion of the population pays it. 3.7% of deaths recorded in the UK in the 2020-21 tax year resulted in inheritance tax liabilities.

Dower is a provision accorded traditionally by a husband or his family, to a wife for her support should she become widowed. It was settled on the bride by agreement at the time of the wedding, or as provided by law.

Marriage in ancient Rome was a fundamental institution of society and was used by Romans primarily as a tool for interfamilial alliances. The institution of Roman marriage was a practice of marital monogamy: Roman citizens could have only one spouse at a time in marriage but were allowed to divorce and remarry. This form of prescriptively monogamous marriage that co-existed with male resource polygyny in Greco-Roman civilization may have arisen from the relative egalitarianism of democratic and republican city-states. Early Christianity embraced this ideal of monogamous marriage by adding its own teaching of sexual monogamy, and perpetrated it worldwide and became as an essential element in many later Western cultures.

International tax law distinguishes between an estate tax and an inheritance tax. An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate of a person who has died. However, this distinction is not always observed; for example, the UK's "inheritance tax" is a tax on the assets of the deceased, and strictly speaking is therefore an estate tax. Inheritance taxes vary widely between countries.

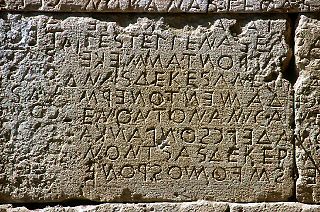

An epikleros was an heiress in ancient Athens and other ancient Greek city states, specifically a daughter of a man who had no sons. In Sparta, they were called patrouchoi (πατροῦχοι), as they were in Gortyn. Athenian women were not allowed to hold property in their own name; in order to keep her father's property in the family, an epikleros was required to marry her father's nearest male relative. Even if a woman was already married, evidence suggests that she was required to divorce her spouse to marry that relative. Spartan women were allowed to hold property in their own right, and so Spartan heiresses were subject to less restrictive rules. Evidence from other city-states is more fragmentary, mainly coming from the city-states of Gortyn and Rhegium.

In the United States, the estate tax is a federal tax on the transfer of the estate of a person who dies. The tax applies to property that is transferred by will or, if the person has no will, according to state laws of intestacy. Other transfers that are subject to the tax can include those made through a trust and the payment of certain life insurance benefits or financial accounts. The estate tax is part of the federal unified gift and estate tax in the United States. The other part of the system, the gift tax, applies to transfers of property during a person's life.

Lex Cincia de donis et muneribus was a law reportedly passed in 204 BC by the tribune Marcus Cincius Alimentus, so documented in Livy. Few provisions of the law are known. One prohibited someone from giving an orator a gift to plead a case. Another limited the value of gifts that could be exchanged between different groups of people. It was passed in the aftermath of the second Punic war, probably for the purpose of reining in aristocratic families' demands for gifts from clients. It may also be related to a similar law, the lex Fufia testamentaria, which limited inheritances of non-blood relatives to 1,000 asses.

Anti-miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalizing interracial marriage sometimes, also criminalizing sex between members of different races.

Ulpian's life table is an ancient Roman annuities table. It is known through a passage, originating from the jurist Aemilius Macer, preserved in edited form in Justinian's Digest. The table appears to provide a rough outline of ancient Roman life expectancy. Although it is not clear what population the table refers to, or how its data was gathered, Richard Duncan-Jones has suggested that it refers to slaves and ex-slaves, who were often the object of testamentary maintenance grants.

The Custom of Paris was one of France's regional custumals of civil law. It was the law of the land in Paris and the surrounding region in the 16th–18th centuries and was applied to French overseas colonies, including New France. First written in 1507 and revised in 1580 and 1605, the Custom of Paris was a compilation and systematization of Renaissance-era customary law. Divided into 16 sections, it contained 362 articles concerning family and inheritance, property, and debt recovery. It was the main source of law in New France from the earliest settlement, but other provincial customs were sometimes invoked in the early period.

The aerarium militare was the military treasury of Imperial Rome. It was instituted by Augustus, the first Roman emperor, as a "permanent revenue source" for pensions (praemia) for veterans of the Imperial Roman army. The treasury derived its funding from new taxes, an inheritance tax and a sales tax, and regularized the ad hoc provisions for veterans that under the Republic often had involved socially disruptive confiscation of property.

Centesima rerum venalium was a 1% tax on goods sold at auction during the Roman empire.

In Ancient Rome, there were four primary kinds of taxation: a cattle tax, a land tax, customs, and a tax on the profits of any profession. These taxes were typically collected by local aristocrats. The Roman state would set a fixed amount of money each region needed to provide in taxes, and the local officials would decide who paid the taxes and how much they paid. Once collected the taxes would be used to fund the military, create public works, establish trade networks, stimulate the economy, and to fund the cursus publicum.

The Vicesima libertatis, also known as the Vicesima Manumissionum was an ancient Republican Roman tax on freed slaves. It is unclear how the tax was collected. One possibility is that, if the master freed the slave the government would tax the master for 5% of the slaves value, while if the slave freed themselves they would be taxed. Another possibility is that the tax was for registering a slave as free, not for freeing them in the first place. Evidence dating back to the Republic suggests that the collection of the tax was likely farmed out to the publicani. By the time of the empire, collection of the tax likely was controlled by the emperor themselves.

References

- ↑ Jane Gardner, "Nearest and Dearest: Liability to Inheritance Tax in Roman Families," in Childhood, Class and Kin in the Roman World pp. 205, 213.

- ↑ Gardner, "Liability to Inheritance Tax," pp. 205, 211.

- ↑ Gardner, "Liability to Inheritance Tax," p. 214; see further Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A.J. McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 19–20, and Beryl Rawson, "The Roman Family in Italy" (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 15–18.

- ↑ Gardner, "Liability to Inheritance Tax," p. 214.

- ↑ Cassius Dio 55.25.5.

- ↑ Gardner, "Liability to Inheritance Tax," p. 205.