Related Research Articles

Charlottesville, colloquially known as C'ville, is an independent city in Virginia, United States. It is the seat of government of Albemarle County, which surrounds the city, though the two are separate legal entities. It is named after Queen Charlotte. At the 2020 census, the city's population was 46,553. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines the City of Charlottesville with Albemarle County for statistical purposes, bringing its population to approximately 160,000. Charlottesville is the heart of the Charlottesville metropolitan area, which includes Albemarle, Buckingham, Fluvanna, Greene, and Nelson counties.

Pentagon City is an unincorporated neighborhood located in the southeast portion of Arlington County, Virginia. It is located near The Pentagon and Arlington National Cemetery.

Coran Capshaw is an American music industry executive, entrepreneur and founder of Red Light Management, a company that represents recording artists.

Black Bottom was a predominantly African American and poor neighborhood in West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was mostly razed for urban renewal in the 1960s.

North Omaha is a community area in Omaha, Nebraska, in the United States. It is bordered by Cuming and Dodge Streets on the south, Interstate 680 on the north, North 72nd Street on the west and the Missouri River and Carter Lake, Iowa on the east, as defined by the University of Nebraska at Omaha and the Omaha Chamber of Commerce.

Fulton Hill is a neighborhood located in the East End of Richmond, Virginia. The name is used for the area stretching from Gillies Creek to the Richmond city limits. The Greater Fulton Hill Civic Association includes Fulton Bottom, part of Montrose Heights and part of Rocketts. Fulton Hill is south of Church Hill and Shockoe Bottom, north of Varina, east of the James River, and west of Sandston. The zip code is 23231.

The Coldstream-Homestead-Montebello community, often abbreviated to C-H-M, is a neighborhood in northeastern Baltimore, Maryland. A portion of the neighborhood has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Coldstream Homestead Montebello Historic District, recognized for the development of a more suburban style of rowhouses.

Rugby Road is a street in Charlottesville, Virginia that serves as the center of the University of Virginia's fraternity and sorority system and its attendant social activity. It is located across the street from central Grounds, beginning at University Avenue across the street from the Rotunda branching off at Preston Avenue and finally curving down to the 250 Bypass, and marks one end of The Corner, a strip of restaurants and stores that cater mainly to students. Rugby Road is lined with a variety of architecturally significant houses from several different decades. Many of these are currently used by fraternities and sororities, although the majority of them were originally intended for single-family use; William Faulkner was one famous resident while he was a writer in residence at the University.

Lane High School, in Charlottesville, Virginia, was a public secondary school serving residents of Charlottesville from 1940 until 1974. It was an all-white school until its court-ordered integration in 1959. Black students formerly attended Burley High School. When Lane became too small to accommodate the student body, it was replaced by Charlottesville High School. In 1981, the building was converted for use as the Albemarle County Office Building, for which it has remained in use until the present day.

Glenwood is a neighborhood in North Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located in the vicinity of North Philadelphia Station to West York Street.

Michael Signer is an American attorney, author, and politician who served as mayor of Charlottesville, Virginia.

Canada was a small community of free African-Americans established near the University of Virginia in Charlottesville in the 19th century. Many residents of Canada were employed by the university. The community existed from the early 19th century until the early 20th century, by which time the increasingly valuable land had been purchased by white speculators. Researchers theorize that the community was named in homage to the country bordering the United States to the north, where slavery had been abolished under the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833.

Roslyn Hill, sometimes called "The Queen of Alberta Street," was one of the original developers of what became the Alberta Arts District of Portland, Oregon, starting in the early 1990s.

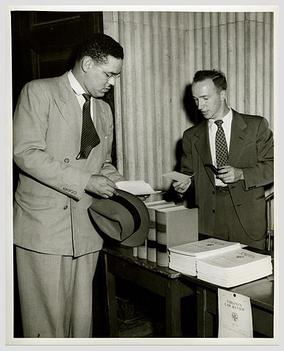

Gregory Hayes Swanson, LL.B, A.B., was an American lawyer who was the first African American to attend the University of Virginia.

The Charlottesville Tom Sox are a collegiate summer baseball team in Charlottesville, Virginia. They play in the southern division of the Valley Baseball League.

Randolph Lewis White (1896–1991) was an African American newspaper publisher, hospital administrator, and civil-rights activist in Charlottesville, Virginia.

Court Square Park is a public park in Charlottesville, Virginia.

The Jefferson School is a historic building in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was built to serve as a segregated high school for African-American students. The school, located on Commerce Street in the downtown Starr Hill neighborhood, was built in four sections starting in 1926, with additions made in 1938–39, 1958, and 1959. It is a large two-story brick building, and the 1938–1939, two-story, rear addition, was partially funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA).

Nannie Cox Jackson was a prominent African-American educator, wealthy property owner and businesswoman in Charlottesville, Virginia.

References

- 1 2 3 "Vinegar Hill | City of Charlottesville". www.charlottesville.org. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ↑ Alexander, James (1942). Early Charlottesville: Recollections of James Alexander, 1828-1874 (2 ed.). Charlottesville, Virginia: The Michie Company, Printers. p. 110. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- 1 2 "In 1965, the city of Charlottesville demolished a thriving black neighborhood". Timeline. 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Vinegar Hill Park process to start this summer ⋅ Charlottesville Tomorrow". Charlottesville Tomorrow. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- 1 2 3 4 "Vinegar Hill | African American Historic Sites Database". African American Historic Sites Database. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ↑ Matthew, Dayna Bowen (1 April 2019). "The "Terminal Condition" Condition in Virginia's Natural Death Act". Virginia Law Review. 73 (4): 749–781. doi:10.2307/1072986. ISSN 0042-6601. JSTOR 1072986. PMID 11652506.

- 1 2 "In 1965, the city of Charlottesville demolished a thriving black neighborhood". Timeline. 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ↑ Eligon, John (2017-08-18). "In Charlottesville, Some Say Statue Debate Obscures a Deep Racial Split". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- ↑ "History and Gardens of Market Street Park | City of Charlottesville".

- ↑ Abramowitz, Sophie; Latterner, Eva; Rosenblith, Gillet (2017-06-23). "Tools of Displacement". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339 . Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ Eiigon, John (18 August 2017). "In Charlottesville, Some Say Statue Debate Obscures a Deep Racial Split". New York Times. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ II, Vann R. Newkirk (2017-08-18). "Black Charlottesville Has Seen This All Before". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2018-09-04.

- ↑ "Going dark: The closure of Random Row Books extinguishes a community light - C-VILLE Weekly". C-VILLE Weekly. 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ↑ "Vinegar Hill Vintage".

- ↑ "Vinegar Hill Magazine".

- ↑ "Charlottesville's last independently owned movie theater goes dark - C-VILLE Weekly". C-VILLE Weekly. 2013-08-06. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- ↑ Moomaw, Graham (7 November 2011). "Charlottesville officially apologizes for razing Vinegar Hill". The Daily Progress. Retrieved 2018-09-01.