The Motion Picture Production Code was the set of industry moral guidelines that was applied to most United States motion pictures released by major studios from 1930 to 1968. It is also popularly known as the Hays Code, after Will H. Hays, who was the president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) from 1922 to 1945. Under Hays' leadership, the MPPDA, later known as the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), adopted the Production Code in 1930, and began rigidly enforcing it in mid-1934. The Production Code spelled out what was acceptable and what was unacceptable content for motion pictures produced for a public audience in the United States.

Project Censored is an American nonprofit media watchdog organization. The group's stated mission is to "educate students and the public about the importance of a truly free press for democratic self-government."

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux was an African-American author, film director and independent producer of more than 44 films. Although the short-lived Lincoln Motion Picture Company was the first movie company owned and controlled by black filmmakers, Micheaux is regarded as the first major African-American feature filmmaker, a prominent producer of race film, and has been described as "the most successful African-American filmmaker of the first half of the 20th century". He produced both silent films and sound films when the industry changed to incorporate speaking actors.

The National Legion of Decency, also known as the Catholic Legion of Decency, was founded in 1933 as an organization dedicated to identifying and combating objectionable content in motion pictures from the point of view of the American Catholic Church. After receiving a stamp of approval from the secular offices behind Hollywood's Production Code, films during this time period were then submitted to the National Legion of Decency to be reviewed prior to their official duplication and distribution to the general public. Condemnation by the Legion would shake a film's core for success because it meant the population of Catholics, some twenty million strong at the time, were forbidden from attending any screening of the film under pain of mortal sin. The efforts to help parishioners avoid films with objectional content backfired when it was found that it helped promote those films in heavily Catholic neighborhoods among Catholics who may have seen the listing as a suggestion. Although the Legion was often envisioned as a bureaucratic arm of the Catholic Church, it instead was little more than a loose confederation of local organizations, with each diocese appointing a local Legion director, usually a parish priest, who was responsible for Legion activities in that diocese.

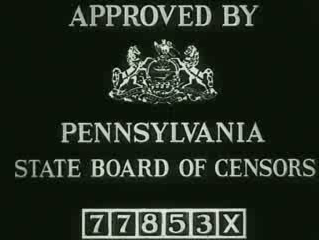

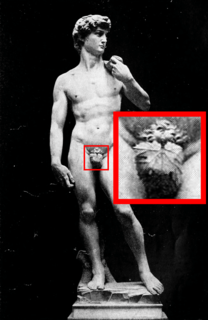

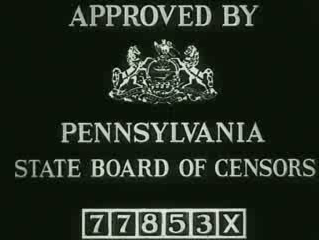

The Pennsylvania State Board of Censors was an organization under the Pennsylvania Department of Education responsible for approving, redacting, or banning motion pictures which it considered "sacrilegious, obscene, indecent, or immoral", or which might pervert morals.

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952),, was a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court which largely marked the decline of motion picture censorship in the United States. It determined that provisions of the New York Education Law which allowed a censor to forbid the commercial showing of a motion picture film it deemed to be "sacrilegious" was a "restraint on freedom of speech" and thereby a violation of the First Amendment.

The race film or race movie was a film type produced entirely in the United States between about 1915 and the early 1950s, consisting of films produced for an all-black audience, featuring black casts.

The Motion Picture Division of the State of New York Education Department, also known variously as the New York State Censorship Board, New York Censor Board, and New York Board of Censors, was an organ of film censorship in the Pre-Code film era.

Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, 236 U.S. 230 (1915), was a United States Supreme Court case in 1915, in which the Court ruled by a 9-0 vote that the free speech protection of the Ohio Constitution, which was substantially similar to the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, did not extend to motion pictures.

Johan Jacobsen was a Danish film director. His parents were theatre manager Jacob Jørgen Jacobsen (1865-1955) and actress Christel Holch (1886-1968).

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information, on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by a government private institutions, and corporations.

Joseph Burstyn was a Polish-American film distributor who specialized in the commercial release of foreign-language and American independent film productions.

The House Behind the Cedars is a 1927 silent race film directed, written, produced and distributed by the noted director Oscar Micheaux. It was loosely adapted from the 1900 novel of the same name by the African-American writer Charles W. Chesnutt, who explored issues of race, class and identity in the post-Civil War South. No print of the film is known to exist, and it is considered lost. Micheaux remade the film in 1932 under the title Veiled Aristocrats.

Veiled Aristocrats is a 1932 American Pre-Code race film directed, written, produced and distributed by Oscar Micheaux. The film deals with the theme of "passing" by mixed-race African Americans to avoid racial discrimination, and is a remake of The House Behind the Cedars (1927), based on a novel by the same name published in 1900 by Charles W. Chesnutt.

A Son of Satan is a 1924 race film directed, written, produced and distributed by Oscar Micheaux. The film follows the misadventures of a man who accepted a bet to spend a night in a haunted house. Micheaux shot the film in The Bronx, New York, and Roanoke, Virginia.

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1965), was a United States Supreme Court case that ended government-operated rating boards with a decision that a rating board could only approve a film and had no power to ban a film. The ruling also concluded that a rating board must either approve a film within a reasonable time, or go to court to stop a film from being shown in theatres. Other court cases determined that television stations are federally licensed, so local rating boards have no jurisdiction over films shown on television. When the movie industry set up its own rating system—the Motion Picture Association of America—most state and local boards ceased operating.

The National Association of the Motion Picture Industry (NAMPI) was a regulatory body created by the Hollywood studios in 1916 to answer demands of censorship. The system consisted of a series of "Thirteen Points", a list of subjects and storylines they promised to avoid. The organization tried to prevent New York from becoming the first state with its own censorship board in 1921, but failed. NAMPI was ineffective and was replaced when the studio hired Will H. Hays to oversee censorship in 1922.

The Vinson Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States from 1946 to 1953, when Fred Vinson served as Chief Justice of the United States. Vinson succeeded Harlan F. Stone as Chief Justice after the latter's death, and Vinson served as Chief Justice until his death, at which point Earl Warren was nominated and confirmed to succeed Vinson.