A number of Latin works on the Life of Muhammad (Vita Mahumeti, Vita Machometi, etc.) were written during the 11th to 13th centuries.

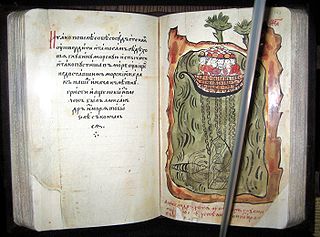

They are ultimately based on the tradition of the Chronographia of Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818), translated into Latin in the 9th century by Anastasius Bibliothecarius, which contained a chapter on the life of Muhammad. The earliest original Latin composition is Eulogius of Córdoba (c. 857). [1]

Saint Theophanes the Confessor was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy, who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before taking up the religious life. Theophanes attended the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 and resisted the iconoclasm of Leo V the Armenian, for which he was imprisoned. He died shortly after his release.

Anastasius Bibliothecarius or Anastasius the Librarian was bibliothecarius and chief archivist of the Church of Rome and also briefly an Antipope.

Saint Eulogius of Córdoba (Spanish: San Eulogio de Córdoba was one of the Martyrs of Córdoba. He flourished during the reigns of the Cordovan emirs Abd-er-Rahman II and Muhammad I.

While Latin biographies of Muhammad in the 11th to 12th century are still in the genre of anti-hagiography, depicting Muhammad as an heresiarch, the tradition develops into the genre of picaresque novel, with Muhammad in the role of the trickster figure, in the 13th century.

In Christian theology, a heresiarch or arch-heretic is an originator of heretical doctrine, or the founder of a sect that sustains such a doctrine.

The picaresque novel is a genre of prose fiction that depicts the adventures of a roguish, but "appealing hero", of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrupt society. Picaresque novels typically adopt a realistic style, with elements of comedy and satire. This style of novel originated in Spain in 1554 and flourished throughout Europe for more than 200 years, though the term "picaresque novel" was only coined in 1810. It continues to influence modern literature. The term is also sometimes used to describe works, like Cervantes' Don Quixote and Charles Dickens' Pickwick Papers, which only contain some of the genre's elements.

In mythology, and in the study of folklore and religion, a trickster is a character in a story, which exhibits a great degree of intellect or secret knowledge, and uses it to play tricks or otherwise disobey normal rules and conventional behaviour.

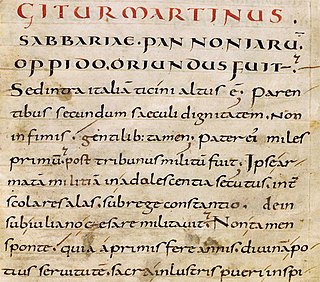

The Vita Mahumeti by Embrico of Mainz (Embricho Moguntinus) is an early example of the genre. The text is in rhyming leonine hexameters, extending to 1,148 lines. It was modelled on the verse hagiography of contemporaries such as Hildebert of Le Mans. It was most likely written between 1072 and 1090. The author of the Vita has been identified with the future provost of Mainz Cathedral, Embricho II by Rotter (1994).

A hagiography is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader. The term hagiography may be used to refer to the biography of a saint or highly developed spiritual being in any of the world's spiritual traditions.

Mainz Cathedral or St. Martin's Cathedral is located near the historical center and pedestrianized market square of the city of Mainz, Germany. This 1000-year-old Roman Catholic cathedral is the site of the episcopal see of the Bishop of Mainz.

Embrico's text is roughly contemporary with the Dei gesta per Francos by Guibert of Nogent. Both texts are the tradition of the biography the Chronographia of Theophanes, including the account of Muhammad's epilepsy and his body being eaten by pigs after his death. [2]

Guibert de Nogent was a Benedictine historian, theologian and author of autobiographical memoirs. Guibert was relatively unknown in his own time, going virtually unmentioned by his contemporaries. He has only recently caught the attention of scholars who have been more interested in his extensive autobiographical memoirs and personality which provide insight into medieval life.

A 12th-century versions include Otia Machometi by Gautier de Compiègne (c. 1155) and Vita Machometi by Adelphus- [3] 13th-century works of the romance type, written in Old French, include The Romance of Muhammad (1258) and The Book of Muhammad's Ladder (1264).

Although the genre is very old, the romance novel or romantic novel discussed in this article is the mass-market version. Novels of this type of genre fiction place their primary focus on the relationship and romantic love between two people, and must have an "emotionally satisfying and optimistic ending." There are many subgenres of the romance novel, including fantasy, historical romance, paranormal fiction, and science fiction. Romance novels are read primarily by women.

Old French was the language spoken in Northern France from the 8th century to the 14th century. In the 14th century, these dialects came to be collectively known as the langue d'oïl, contrasting with the langue d'oc or Occitan language in the south of France. The mid-14th century is taken as the transitional period to Middle French, the language of the French Renaissance, specifically based on the dialect of the Île-de-France region.