The Italic languages form a branch of the Indo-European language family, whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BC. The most important of the ancient Italic languages was Latin, the official language of ancient Rome, which conquered the other Italic peoples before the common era. The other Italic languages became extinct in the first centuries AD as their speakers were assimilated into the Roman Empire and shifted to some form of Latin. Between the third and eighth centuries AD, Vulgar Latin diversified into the Romance languages, which are the only Italic languages natively spoken today, while Literary Latin also survived.

Minerva is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. She is also a goddess of warfare, though with a focus on strategic warfare, rather than the violence of gods such as Mars. Beginning in the second century BC, the Romans equated her with the Greek goddess Athena. Minerva is one of the three Roman deities in the Capitoline Triad, along with Jupiter and Juno.

The Old Italic scripts are a family of ancient writing systems used in the Italian Peninsula between about 700 and 100 BC, for various languages spoken in that time and place. The most notable member is the Etruscan alphabet, which was the immediate ancestor of the Latin alphabet used by more than 100 languages today, including English. The runic alphabets used in Northern Europe are believed to have been separately derived from one of these alphabets by the 2nd century AD.

Vestini were an Italic tribe who occupied the area of the modern Abruzzo, included between the Gran Sasso and the northern bank of the Aterno river. Their main centres were Pitinum (near modern L'Aquila), Aufinum (Ofena), Peltuinum, Pinna (Penne) and Aternum (Pescara, shared with the Marrucini).

Ancient art refers to the many types of art produced by the advanced cultures of ancient societies with different forms of writing, such as those of ancient China, India, Mesopotamia, Persia, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The art of pre-literate societies is normally referred to as prehistoric art and is not covered here. Although some pre-Columbian cultures developed writing during the centuries before the arrival of Europeans, on grounds of dating these are covered at pre-Columbian art and articles such as Maya art, Aztec art, and Olmec art.

The Samnites were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

The Etruscan alphabet was used by the Etruscans, an ancient civilization of central and northern Italy, to write their language, from about 700 BC to sometime around 100 AD.

The Senones or Senonii were an ancient Gallic tribe dwelling in the Seine basin, around present-day Sens, during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Picenum was a region of ancient Italy. The name was assigned by the Romans, who conquered and incorporated it into the Roman Republic. Picenum became Regio V in the Augustan territorial organisation of Roman Italy. It is now in Marche and the northern part of Abruzzo.

South Picene is an extinct Italic language belonging to the Sabellic subfamily. It is apparently unrelated to the North Picene language, which is not understood and therefore unclassified. South Picene texts were at first relatively inscrutable even though some words were clearly Indo-European. The discovery in 1983 that two of the apparently redundant punctuation marks were in reality simplified letters led to an incremental improvement in their understanding and a first translation in 1985. Difficulties remain. It may represent a third branch of Sabellic, along with Oscan and Umbrian ,, or the whole Sabellic linguistic area may be best regarded as a linguistic continuum. The paucity of evidence from most of the 'minor dialects' contributes to these difficulties.

North Picene, also known as North Picenian or Northern Picene, is a supposed ancient language, which may have been spoken in part of central-eastern Italy; alternatively the evidence for the language may be a hoax, with the language never having existed. The evidence for the language consists of four inscriptions apparently dating from the 1st millennium BC, three of them no more than small broken fragments. It is written in a form of the Old Italic alphabet. While its texts are easily transliterated, none of them have been translated so far. It is not possible to determine whether it is related to any other known language. Despite the use by modern scholars of a similar name, it does not appear that North Picene is closely related to South Picene, and they may not be related at all. The total number of words in the inscriptions is about 60. It is not even certain that the inscriptions are all in one language.

Capestrano is a comune and small town with 885 inhabitants (2017), in the Province of L'Aquila, Abruzzo, Italy. It is located in the Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga National Park.

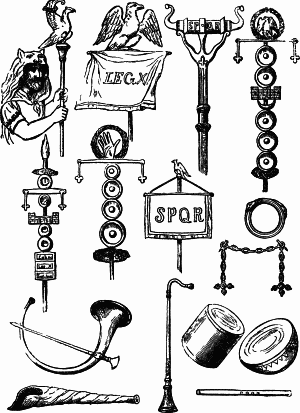

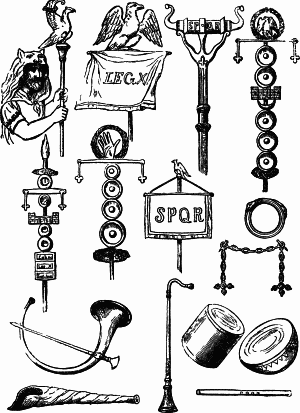

Roman military personal equipment was produced in large numbers to established patterns, and used in an established manner. These standard patterns and uses were called the res militaris or disciplina. Its regular practice during the Roman Republic and Roman Empire led to military excellence and victory. The equipment gave the Romans a very distinct advantage over their barbarian enemies, especially so in the case of armour. This does not mean that every Roman soldier had better equipment than the richer men among his opponents. Roman equipment was not of a better quality than that used by the majority of Rome's adversaries. Other historians and writers have stated that the Roman army's need for large quantities of "mass produced" equipment after the so-called "Marian Reforms" and subsequent civil wars led to a decline in the quality of Roman equipment compared to the earlier Republican era:

The production of these kinds of helmets of Italic tradition decreased in quality because of the demands of equipping huge armies, especially during civil wars...The bad quality of these helmets is recorded by the sources describing how sometimes they were covered by wicker protections, like those of Pompeius' soldiers during the siege of Dyrrachium in 48 BC, which were seriously damaged by the missiles of Caesar's slingers and archers.

It would appear that armour quality suffered at times when mass production methods were being used to meet the increased demand which was very high the reduced size cuirasses would also have been quicker and cheaper to produce, which may have been a deciding factor at times of financial crisis, or where large bodies of men were required to be mobilized at short notice, possibly reflected in the poor-quality, mass produced iron helmets of Imperial Italic type C, as found, for example, in the River Po at Cremona, associated with the Civil Wars of AD 69 AD; Russell Robinson, 1975, 67

Up until then, the quality of helmets had been fairly consistent and the bowls well decorated and finished. However, after the Marian Reforms, with their resultant influx of the poorest citizens into the army, there must inevitably have been a massive demand for cheaper equipment, a situation which can only have been exacerbated by the Civil Wars...

The pileus was a brimless felt cap worn in Ancient Greece, Etruria, Illyria, later also introduced in Ancient Rome. The pileus also appears on Apulian red-figure pottery.

The Picentes or Piceni or Picentini were an ancient Italic people who lived from the 9th to the 3rd century BC in the area between the Foglia and Aterno rivers, bordered to the west by the Apennines and to the east by the Adriatic coast. Their territory, known as Picenum, therefore included all of today's Marche and the northern part of Abruzzo. Piceni derived their culture and genetic ancestry from the Early Bronze Age Cetina culture at the other side of the Adriatic Sea, and Late Bronze Age Hallstatt culture along the Danube River, as new research confirms.

The Phrygian helmet, also known as the Thracian helmet, was a type of helmet that originated in ancient Greece, towards the close of the classical period and was used throughout the Hellenistic world until well into the period of the Roman Republic. Widely used by Greek, Macedonian, Diadochi, Italic peoples, Etruscans, Thracian, Phrygian and Dacian warriors throughout the Hellenistic and Roman republican period and by some ethnicities into Roman imperial times.

The Waterloo Helmet is a pre-Roman Celtic bronze ceremonial horned helmet with repoussé decoration in the La Tène style, dating to circa 150–50 BC, that was found in 1868 in the River Thames by Waterloo Bridge in London, England. It is now on display at the British Museum in London.

Illyrian weaponry played an important role in the makeup of Illyrian armies and in conflicts involving the Illyrians. Of all the ancients sources the most important and abundant writings are those of Ennius, a Roman poet of Messapian origin. Weapons of all sorts were also placed intact in the graves of Illyrian warriors and provide a detailed picture for archaeologists on the distribution and development of Illyrian weaponry.

Robert Ross Holloway was an American archaeologist, founder with Rolf Winkes of the Center for Classical Art and Archaeology at Brown University, and the Elisha Benjamin Andrews Professor Emeritus of Brown University, where he taught from 1964 to his retirement in 2006.

Ross Cowan is a British historian and author specialising in Roman military history.