Related Research Articles

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of various kinds, including those characterized by close kinship relations. By the 17th century, the term began to refer to physical (phenotypical) traits, and then later to national affiliations. Modern science regards race as a social construct, an identity which is assigned based on rules made by society. While partly based on physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent physical or biological meaning. The concept of race is foundational to racism, the belief that humans can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another.

French Equatorial Africa was a federation of French colonial territories in Equatorial Africa which consisted of Gabon, the French Congo, Ubangi-Shari, and Chad. It existed from 1910 to 1958 and its administration was based in Brazzaville.

Environmental determinism is the study of how the physical environment predisposes societies and states towards particular development trajectories. Jared Diamond, Jeffrey Herbst, Ian Morris, and other social scientists sparked a revival of the theory during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This "neo-environmental determinism" school of thought examines how geographic and ecological forces influence state-building, economic development, and institutions. Many scholars underscore that this original approach was used to encourage colonialism and eurocentrism, and devalued human agency in non-Western societies, whereas modern figures like Diamond have instead used the approach as an explanation that rejects racism.

Underdevelopment, in the context of international development, reflects a broad condition or phenomena defined and critiqued by theorists in fields such as economics, development studies, and postcolonial studies. Used primarily to distinguish states along benchmarks concerning human development—such as macro-economic growth, health, education, and standards of living—an "underdeveloped" state is framed as the antithesis of a "developed", modern, or industrialized state. Popularized, dominant images of underdeveloped states include those that have less stable economies, less democratic political regimes, greater poverty, malnutrition, and poorer public health and education systems.

This article covers the cultural history of the United States since its founding in the late 18th century. The region has had patterns of original settlement by different peoples, & later settler colonial states & societal setups. Various immigrant groups have been at play in the formation of the nation's culture. While different ethnic groups may display their own insular cultural aspects, throughout time a broad American culture has developed that encompasses the entire country. Developments in the culture of the United States in modern history have often been followed by similar changes in the rest of the world.

The Fang people, also known as Fãn or Pahouin, are a Bantu ethnic group found in Equatorial Guinea, northern Gabon, and southern Cameroon. Representing about 85% of the total population of Equatorial Guinea, concentrated in the Río Muni region, the Fang people are its largest ethnic group. The Fang are also the largest ethnic group in Gabon, making up about a quarter of the population.

The Kpelle people are the largest ethnic group in Liberia. They are located primarily in an area of central Liberia extending into Guinea. They speak the Kpelle language, which belongs to the Mande language family.

European colonialism and colonization was the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over other societies and territories, founding a colony, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically. For example, colonial policies, such as the type of rule implemented, the nature of investments, and identity of the colonizers, are cited as impacting postcolonial states. Examination of the state-building process, economic development, and cultural norms and mores shows the direct and indirect consequences of colonialism on the postcolonial states.

Geography and wealth have long been perceived as correlated attributes of nations. Scholars such as Jeffrey D. Sachs argue that geography has a key role in the development of a nation's economic growth. For instance, nations that reside along coastal regions, or those who have access to a nearby water source, are more plentiful and able to trade with neighboring nations. In addition, countries that have a tropical climate face a significant amount of difficulties such as disease, intense weather patterns, and lower agricultural productivity. This thesis is supported by the fact that the volumes of UV radiation have a negative impact on economic activity. There are a number of studies confirming that spatial development in countries with higher levels of economic development differs from countries with lower levels of development. The correlation between geography and a nation's wealth can be observed by examining a country's GDP per capita, which takes into account a nation's economic output and population.

The Mongo people are an ethnic group who live in the equatorial forest of Central Africa. They are the largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of Congo, highly influential in its north region. The Mongo people are a diverse collection of sub-ethnic groups who are referred to as AnaMongo. The Mongo (Anamongo) subgroups include the Mongo, Batetela, Bakusu, Ekonda, Bolia, Nkundo, Bashilele, Lokele, Topoke, Iyadjima, Ngole, Ngando, Ndengese, Babembe, Bakuba, Sengele, Sakata, Mpama, Ngengele, Ntomba, Mbelo, Mbole, Wongo and more. 33% of the Congolese population are mainly made up of the Anamongo who occupy 31% of the area of the DRC. The Mongo (Anamongo) occupy 14 provinces particularly the province of Equateur,Tshopo, Tshuapa, Mongala, Kwilu, in Maï Ndombe, Kongo-Centrale, in Kasai, in Sankuru, Maniema, North Kivu and South Kivu, Tanganiyka (Katanga) and Ituri province. Their highest presence is in the province of Équateur and the northern parts of the Bandundu Province(Maï Ndombe).

Postcolonialism is the critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic legacy of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and exploitation of colonized people and their lands. The field started to emerge in the 1960s, as scholars from previously colonized countries began publishing on the lingering effects of colonialism, developing a critical theory analysis of the history, culture, literature, and discourse of imperial power.

Spheres of exchange is a heuristic tool for analyzing trading restrictions within societies that are communally governed and where resources are communally available. Goods and services of specific types are relegated to distinct value categories, and moral sanctions are invoked to prevent exchange between spheres. It is a classic topic in economic anthropology.

The coloniality of power is a concept interrelating the practices and legacies of European colonialism in social orders and forms of knowledge, advanced in postcolonial studies, decoloniality, and Latin American subaltern studies, most prominently by Anibal Quijano. It identifies and describes the living legacy of colonialism in contemporary societies in the form of social discrimination that outlived formal colonialism and became integrated in succeeding social orders. The concept identifies the racial, political and social hierarchical orders imposed by European colonialism in Latin America that prescribed value to certain peoples/societies while disenfranchising others.

The anthropology of development is a term applied to a body of anthropological work which views development from a critical perspective. The kind of issues addressed, and implications for the approach typically adopted can be gleaned from a list questions posed by Gow (1996). These questions involve anthropologists asking why, if a key development goal is to alleviate poverty, is poverty increasing? Why is there such a gap between plans and outcomes? Why are those working in development so willing to disregard history and the lessons it might offer? Why is development so externally driven rather than having an internal basis? In short, why is there such a lack of planned development?

In political anthropology, a theatre state is a political state directed towards the performance of drama and ritual rather than towards more conventional ends such as warfare and welfare. Power in a theatre state is exercised through spectacle. The term, coined by Clifford Geertz (1926-2006) in 1980 in reference to political practice in the nineteenth-century Balinese Negara, has since expanded in usage. Hunik Kwon and Byung-Ho Chung, for example, regard contemporary North Korea as a theatre state. In Geertz's original usage, the concept of the theatre state contests the notion that precolonial society can be analysed in the conventional discourse of Oriental despotism.

State formation is the process of the development of a centralized government structure in a situation in which one did not exist. State formation has been a study of many disciplines of the social sciences for a number of years, so much so that Jonathan Haas writes, "One of the favorite pastimes of social scientists over the course of the past century has been to theorize about the evolution of the world's great civilizations."

Decoloniality is a school of thought that aims to delink from Eurocentric knowledge hierarchies and ways of being in the world in order to enable other forms of existence on Earth. It critiques the perceived universality of Western knowledge and the superiority of Western culture, including the systems and institutions that reinforce these perceptions. Decolonial perspectives understand colonialism as the basis for the everyday function of capitalist modernity and imperialism. Decoloniality emerged as part of a South America movement examining the role of the European colonization of the Americas in establishing Eurocentric modernity/coloniality. Decolonial theory and practice have recently been subject to increasing critique. For example, Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò argued that it is analytically unsound, that "coloniality" is often conflated with "modernity", and that "decolonisation" becomes an impossible project of total emancipation. Jonatan Kurzwelly and Malin Wilckens, used the example of decolonisation of academic collections of human remains - which were collected during colonial times to support racist theories and give legitimacy to colonial oppression -, and showed how both contemporary scholarly methods and political practice perpetuate reified and essentialist notions of identities.

The Beti people are a Central African ethnic group primarily found in central Cameroon. They are also found in Equatorial Guinea and northern Gabon. They are closely related to the Bulu people, the Fang people and the Yaunde people, who are all sometimes grouped as Ekang.

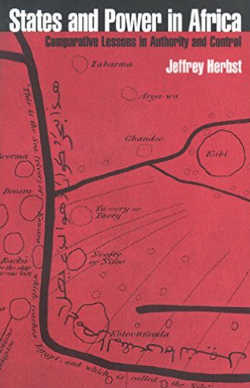

States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control is a book on African state-building by Jeffrey Herbst, former Professor of Politics and International Affairs at Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. The book was a co-winner of the 2001 Gregory Luebbert Book Award from the American Political Science Association in comparative politics. It was also a finalist for the 2001 Herskovits Prize awarded by the African Studies Association.

Sharifism is a term used to describe the system in pre-colonial Morocco in which the shurafā' —descendants of the Islamic prophet Muhammad —held a privileged religious and political position in society. Those who claimed this lineage were regarded as a kind of nobility and were privileged, in the words of Sahar Bazzaz, "as political agents, as interlocutors between various sectors of society, and as would be dynasts of Morocco." They were additionally believed to possess baraka, or blessing power. Claiming this lineage also served to justify authority; the Idrisi dynasty (788-974), the Saadi dynasty (1510-1659), and the 'Alawi dynasty (1631–present) all claimed lineage from Ahl al-Bayt.

References

- ↑ Berry, Sara (1993). No Condition is Permanent: The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Sub-Saharan Africa. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Johnson-Hanks, Jennifer (2006). Uncertain Honor: Modern Motherhood in an African Crisis. University of Chicago Press. p. 30. ISBN 9780226401812.

- ↑ Little, Kenneth (1951). The Mende of Sierra Leone: A West African People in Transition. Routledge & K. Paul.

- ↑ Fallers, Lloyd A. (1964). The King's Men: Leadership and Status in Buganda on the Eve of Independence. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Schneider, David Murray (1968). American Kinship: A Cultural Account. Prentice-Hall.

- ↑ Bledsoe, Caroline H. (1980). Women and Marriage in Kpelle Society. Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Guyer, Jane I.; Samuel M. Eno Belinga (1995). "Wealth in People as Wealth in Knowledge: Accumulation and Composition in Equatorial Africa". The Journal of African History. 36 (1): 91–120. doi:10.1017/S0021853700026992. S2CID 162801990.

- ↑ Argenti, Nicolas (2007). The Intestines of the State: Youth, Violence, and Belated Histories in the Cameroon Grassfields. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Guyer, Jane I.; Samuel M. Eno Belinga (1995). "Wealth in People as Wealth in Knowledge: Accumulation and Composition in Equatorial Africa". The Journal of African History 36 (1): 91–120. doi:10.1017/S0021853700026992

- ↑ Herbst, Jeffrey. ""Power and Space in Precolonial Africa" and "The Europeans and the African Problem"" States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. 35.

- ↑ Herbst, Jeffrey. ""Power and Space in Precolonial Africa" and "The Europeans and the African Problem"" States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. 35-37.

- ↑ Herbst, Jeffrey. ""Power and Space in Precolonial Africa" and "The Europeans and the African Problem"" States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000. 35-96.