A night fighter is a largely historical term for a fighter or interceptor aircraft adapted or designed for effective use at night, during periods of adverse meteorological conditions, or in otherwise poor visibility. Such designs were in direct contrast to day fighters: fighters and interceptors designed primarily for use during the day or during good weather. The concept of the night fighter was developed and experimented with during the First World War but would not see widespread use until WWII. The term would be supplanted by “all-weather fighter/interceptor” post-WWII, with advancements in various technologies permitting the use of such aircraft in virtually all conditions.

Josef Kammhuber was a career officer who served in the Imperial German Army, the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany and the post-World War II German Air Force. During World War II, he was the first general of night fighters in the Luftwaffe.

The Kammhuber Line was the name given by the Allies to the German night-fighter air-defence system established in western Europe in July 1940 by Colonel Josef Kammhuber. It consisted of a series of control sectors equipped with radars and searchlights and an associated night fighter. Each sector would direct the night fighter into visual range to target intruding bombers.

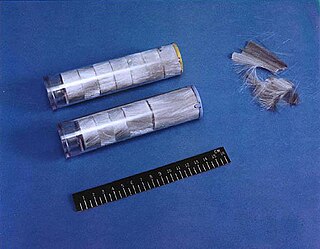

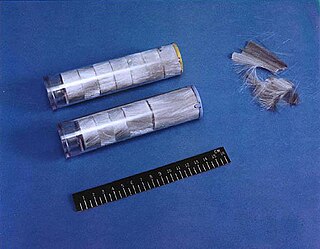

Chaff, originally called Window or Düppel, is a radar countermeasure involving the dispersal of thin strips of aluminium, metallized glass fiber, or plastic. Dispersed chaff produces a large radar cross section intended to blind or disrupt radar systems.

Heinz-Wolfgang Schnaufer was a German Luftwaffe night-fighter pilot and the highest-scoring night fighter ace in the history of aerial warfare. A flying ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during combat. All Schnaufer's 121 victories were claimed during World War II, mostly against British four-engine bombers, for which he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds, Germany's highest military decoration at the time, on 16 October 1944. He was nicknamed "The Spook of St. Trond", from the location of his unit's base in occupied Belgium.

The bomber stream was a saturation attack tactic developed by the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command to overwhelm the nighttime German aerial defences of the Kammhuber Line during World War II.

The Battle of Berlin was a bombing campaign against Berlin by RAF Bomber Command, along with raids on other German cities to keep German defences dispersed and which was a part of the bombing of Berlin during the strategic bombing of Germany in the Second World War. Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris, Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief (AOC-in-C) Bomber Command, believed that "we can wreck Berlin from end to end if the USAAF come in with us. It will cost us between 400 and 500 aircraft. It will cost Germany the war".

Kurt Welter was a German Luftwaffe fighter ace and the most successful Jet Expert of World War II. A flying ace or fighter ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. He claimed a total of 63 aerial victories—that is, 63 aerial combat encounters resulting in the destruction of the enemy aircraft—achieved in 93 combat missions. He recorded 56 victories at night, including 33 Mosquitos, and scored more aerial victories from a jet fighter aircraft than anyone else in World War II and possibly in aviation history. However this score is a matter of controversy; research of Royal Air Force losses suggests Welter overclaimed Mosquito victories considerably. Against this, Luftwaffe claims were very strict, requiring confirmation and proof by witnesses: The remains of aircraft shot down and crashed would be verifiable and recorded on the ground in the sector claimed.

The Helmore/GEC Turbinlite was a 2,700 million candela (2.7 Gcd) searchlight fitted in the nose of a number of British Douglas Havoc night fighters during the early part of the Second World War and around the time of The Blitz. The Havoc was guided to enemy aircraft by ground radar and its own radar. The searchlight would then be used to illuminate attacking enemy bombers for defending fighters accompanying the Havoc to shoot down. In practice the Turbinlite was not a success, and the introduction of higher performance night fighters with their own radar meant they were withdrawn from service in early 1943.

Operation Steinbock or Operation Capricorn, sometimes called the Baby Blitz or Little Blitz, was a strategic bombing campaign by the German Air Force during the Second World War. It targeted southern England and lasted from January to May 1944. Steinbock was the last strategic air offensive by the German bomber arm during the conflict.

The Defence of the Reich is the name given to the strategic defensive aerial campaign fought by the Luftwaffe of Nazi Germany over German-occupied Europe and Germany during World War II against the Allied strategic bombing campaign. Its aim was to prevent the destruction of German civilians, military and civil industries by the Western Allies. The day and night air battles over Germany during the war involved thousands of aircraft, units and aerial engagements to counter the Allies bombing campaigns. The campaign was one of the longest in the history of aerial warfare and with the Battle of the Atlantic and the Allied naval blockade of Germany was the longest of the war. The Luftwaffe fighter force defended the airspace of German-occupied Europe against attack, first by RAF Bomber Command and then against the RAF and United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) in the Combined Bomber Offensive.

Jagdgeschwader 300 was a Luftwaffe fighter-wing of World War II. JG 300 was formed on June 26, 1943 in Deelen as Stab/Versuchskommando Herrmann, from July 18, 1943 as Stab/JG Herrmann and finally renamed on August 20, 1943 to Stab/JG 300. Its first Geschwaderkommodore was Oberstleutnant Hajo Herrmann.

Friedrich-Karl Müller — "Nasen-Müller" — was a Luftwaffe night fighter ace during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, awarded by Nazi Germany to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership.

Nachtjagdgeschwader 1 (NJG 1) was a German Luftwaffe night fighter-wing of World War II. NJG 1 was formed on 22 June 1940 and comprised four Gruppen (groups). NJG 1 was created as an air defence unit for the Defence of the Reich campaign; an aerial war waged by the Luftwaffe against the bombing of the German Reich by RAF Bomber Command and the United States Air Force. In 1941 airborne radar was introduced with radar operators, and standardised in 1942 and 1943. Consequently, a large number of German night fighter aces existed within NJG 1.

Nachtjagdgeschwader 2 was a German Luftwaffe night fighter and night intruder wing during World War II.

The Battle of the Ruhr was a strategic bombing campaign against the Ruhr Area in Nazi Germany carried out by RAF Bomber Command during the Second World War. The Ruhr was the main centre of German heavy industry with coke plants, steelworks, armaments factories and ten synthetic oil plants. The British attacked 26 targets identified in the Combined Bomber Offensive. Targets included the Krupp armament works (Essen), the Nordstern synthetic oil plant at Gelsenkirchen and the Rheinmetall–Borsig plant in Düsseldorf, which was evacuated during the battle. The battle included cities such as Cologne not in the Ruhr proper but which were in the larger Rhine-Ruhr region and considered part of the Ruhr industrial complex. Some targets were not sites of heavy industry but part of the production and movement of materiel.

I. Jagdkorps was formed 15 September 1943 in Zeist from the XII. Fliegerkorps and the Luftwaffenbefehlshaber Mitte, and later subordinated to the Luftflotte Reich. The Stab relocated to Brunswick-Querum in March 1944 and to Treuenbrietzen in October 1944. The unit was disbanded on 26 January 1945 and its obligations were taken over by IX.(J) Fliegerkorps.

Zahme Sau was a night fighter interception tactic conceived by Viktor von Loßberg and introduced by the German Luftwaffe in 1943. As a raid approached, the fighters were scrambled and collected to orbit one of several radio beacons throughout Germany, ready to be directed en masse into the bomber stream by running commentaries from the Jagddivision. Once in the stream, fighters made radar contact with bombers, and attacked them for as long as they had fuel and ammunition.

Viktor von Loßberg was a German air officer during World War II. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany. Loßberg was instrumental in conceiving the concept of Zahme Sau, a night fighter tactic of the Luftwaffe.

The Seeburg plotting table was a mechanical plotting table used by Nazi Germany in their operation rooms to track aircraft and coordinate operations during World War II. It was produced by Siemens.