Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852), which depicts the harsh conditions experienced by enslaved African Americans. The book reached an audience of millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and in Great Britain, energizing anti-slavery forces in the American North, while provoking widespread anger in the South. Stowe wrote 30 books, including novels, three travel memoirs, and collections of articles and letters. She was influential both for her writings as well as for her public stances and debates on social issues of the day.

The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson, "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the 77 slaves who tried to escape from Washington, D.C. on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

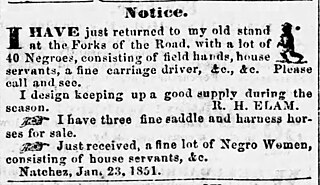

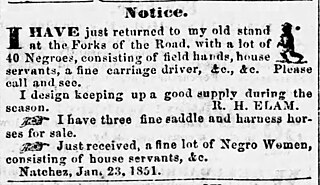

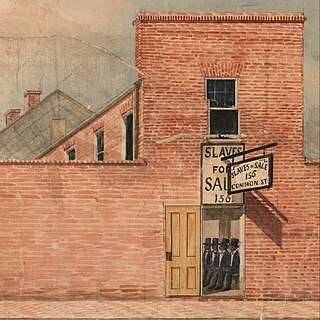

The Natchez, Mississippi slave market was a slave market in Natchez, Mississippi in the United States. Slaves were originally sold throughout the area, including along the Natchez Trace that connected the settlement with Nashville, along the Mississippi River at Natchez-Under-the-Hill, and throughout town. From 1833 to 1863, the Forks of the Road slave market was located about a mile from downtown Natchez at the intersection of Liberty Road and Washington Road, which has since been renamed to D'Evereux Drive in one direction and St. Catherine Street in the other. The market differed from many other slave sellers of the day by offering individuals on a first-come first-serve basis rather than selling them at auction, either singly or in lots. At one time the Forks of the Road was the second-largest slave market in the United States, trailing only New Orleans.

Byrd Hill was a slave trader of Tennessee and Mississippi prior to the American Civil War. Byrd Hill has been described as one of the "big four" slave traders in the centrally located city of Memphis on the Mississippi River. Hill was partners for a time with Nathan Bedford Forrest and is believed to have resold six of the Africans illegally trafficked to the United States on the Wanderer in 1859. Hill also made a fleeting appearance in Harriet Beecher Stowe's A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin.

This is a bibliography of works regarding the internal or domestic slave trade in the United States.

Capt. Montgomery Little, CSA was an American slave trader and a Confederate Army cavalry officer who served in Nathan Bedford Forrest's Escort Company. Little was killed in action during the American Civil War at the Battle of Thompson's Station.

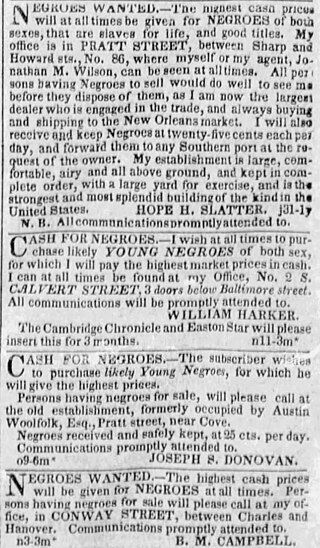

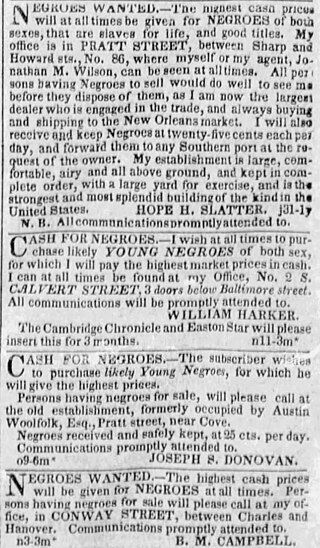

Bernard Moore Campbell and Walter L. Campbell operated an extensive slave-trading business in the antebellum U.S. South. B. M. Campbell, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Joseph S. Donovan, and Hope H. Slatter, has been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9,000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans." Bernard and Walter were brothers.

Fugitive slave advertisements in the United States or runaway slave ads, were paid classified advertisements describing a missing person and usually offering a monetary reward for the recovery of the valuable chattel. Fugitive slave ads were a unique vernacular genre of non-fiction specific to the antebellum United States. These ads often include detailed biographical information about individual enslaved Americans including "physical and distinctive features, literacy level, specialized skills," and "if they might have been headed for another plantation where they had family, or if they took their children with them when they ran."

Jordan Arterburn (1808–1875) and Tarlton Arterburn (1810–1883) were brothers and interstate slave traders of the 19th-century United States. They typically bought enslaved people in their home state of Kentucky in the upper south, and then moved them to Mississippi in the lower south, where there was a constant demand for enslaved laborers on the plantations of King Cotton. Their "negroes wanted" advertisements ran in Louisville newspapers almost continuously from 1843 to 1859. In 1876, Tarlton Arterburn claimed they had taken profits of "30 to 40 percent a head" during their slave-trading days, and that Northern abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe had visited the Arterburn slave pen in Louisville while researching Uncle Tom's Cabin and A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. There is now a historical marker in Louisville at former site of the Arterburn slave jail, acknowledging the myriad abuses and human-rights violations that took place there.

Theophilus Freeman was a 19th-century American slave trader of Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi. He was known in his own time as wealthy and problematic. Freeman's business practices were described in two antebellum American slave narratives—that of John Brown and that of Solomon Northup—and he appears as a character in both filmed dramatizations of Northrup's Twelve Years a Slave.

Joseph S. Donovan was an American slave trader known for his slave jails in Baltimore, Maryland. Donovan was a major participant in the interregional slave trade, building shipments of enslaved people from the Upper South and delivering them to the Deep South where they would be used, for the most part, on cotton and sugar plantations. As one Baltimore historical researcher and tour guide summarized, "the change from raising tobacco to wheat in the region caused a surplus of labor, whereas the South needed more labor due to the invention of the cotton gin". Donovan, in company with Austin Woolfolk, Bernard M. Campbell, and Hope H. Slatter, have been described as one of the "tycoons of the slave trade" in the Upper South, "responsible for the forced departures of approximately 9000 captives from Baltimore to New Orleans."

Jonathan Means Wilson, usually advertising as J. M. Wilson, was a 19th-century slave trader of the United States who trafficked people from the Upper South to the Lower South as part of the interstate slave trade. Originally a trading agent and associate to Baltimore traders, he later operated a slave depot in New Orleans. At the time of the 1860 U.S. census of New Orleans, Wilson had the second-highest net worth of the 34 residents who listed their occupation as "slave trader".

Seth Woodroof was a slave trader based in Lynchburg in central Virginia, United States. He was an interstate trader who ran what the Lynchburg Museum called the "most active and infamous" slave pen in the city. He is believed to have been actively trading from approximately 1830 until the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861. Woodroof sat on the Lynchburg city council from 1858 to 1865.

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

Family separation in American slavery was extremely common. According to one historian of the slave trade in the United States, "The magnitude of the trade, in terms of the lives it affected and families it destroyed, is without a doubt greater than any Civil War battlefield." One survivor of American slavery told the WPA Slave Narratives project, "If you want to know what unhappiness means, just stand on the slave block and hear the auctioneer's voice selling you away from the folks you love." There is widespread evidence of the pervasive nature of family separation: "A central feature of virtually every slave autobiography and of many of the slave interviews, for example, is the trauma caused slaves by forced family separation."

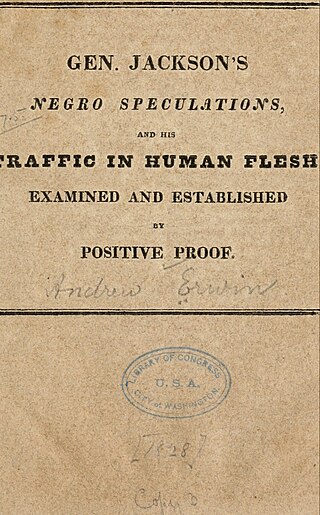

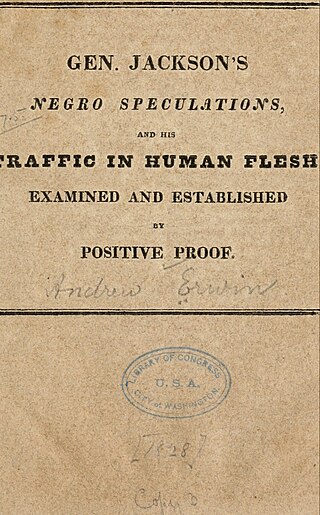

The question of whether Andrew Jackson had been a "negro trader" was a campaign issue during the 1828 United States presidential election. Jackson denied the charges, and the issue failed to connect with the electorate. However, Jackson had indeed been a "speculator in slaves," participating in the interstate slave trade between Nashville, Tennessee and the slave markets of the lower Mississippi River valley at Natchez and New Orleans.

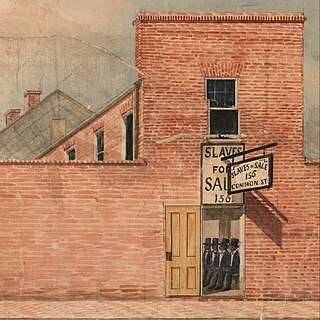

New Orleans, Louisiana was a major, if not the major, slave market of the lower Mississippi River valley of the United States from approximately 1830 until the American Civil War. Slaves from the upper south were trafficked by land and by sea to New Orleans where they were sold at a markup to the cotton and sugar plantation barons of the region.

John W. Lindsey was a slave trader based in Montgomery, Alabama, United States in the 1840s and 1850s.