The Canning Stock Route is a track that runs from Halls Creek in the Kimberley region of Western Australia to Wiluna in the mid-west region. With a total distance of around 1,850 km (1,150 mi) it is claimed to be the longest historic stock route in the world.

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho, bordered with the Cape Colony, Natal Colony and Orange River Colony until 1910 and completely surrounded by South Africa from 1910. Though the Basotho and their territory had been under British control starting in 1868, the rule by Cape Colony was unpopular and unable to control the territory. As a result, Basutoland was brought under direct authority of Queen Victoria, via the High Commissioner, and run by an Executive Council presided over by a series of British Resident Commissioners.

The Orange Free State was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Empire at the end of the Second Boer War in 1902. It is one of the three historical precursors to the present-day Free State province.

A Bantustan was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa, as a part of its policy of apartheid.

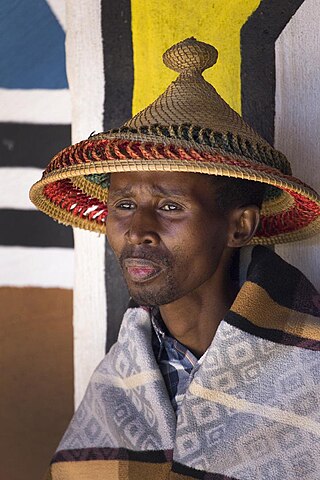

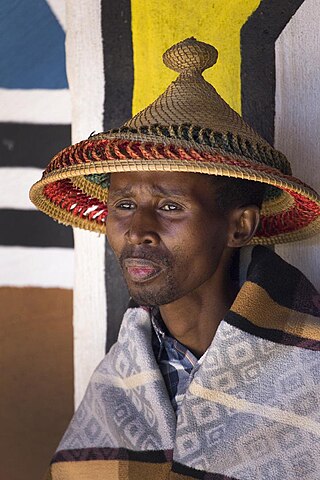

The Sotho, also known as the Basotho, are a Sotho-Tswana ethnic group native to Southern Africa. They primarily inhabit the regions of Lesotho and South Africa.

Moshoeshoe I was the first king of Lesotho. He was the first son of Mokhachane, a minor chief of the Bamokoteli lineage, a branch of the Koena (crocodile) clan. In his youth, he helped his father gain power over some other smaller clans. At the age of 34 Moshoeshoe formed his own clan and became a chief. He and his followers settled at the Butha-Buthe Mountain. He became the first and longest-serving King of Lesotho in 1822.

The Thembu are Xhosa people who lived in the Thembu Kingdom.

Kgosi (Chief) Galeshewe,, was a chief of the Batlhaping group in South Africa. He was an anti-colonial revolutionary and orchestrated rebellions against the Cape Colony government. The Galeshewe Township in the Sol Plaatje Municipality, Kimberley, has been named after him. A South African Navy fast attack craft has also been named after him. Galeshewe was born in 1835 near Taung, South Africa.

Thaba Bosiu is a constituency and sandstone plateau with an area of approximately 2 km2 (0.77 sq mi) and a height of 1,804 meters above sea level. It is located between the Orange and Caledon Rivers in the Maseru District of Lesotho, 24 km east of the country's capital Maseru. It was once the capital of Lesotho, having been King Moshoeshoe's stronghold.

The Transvaal Civil War was a series of skirmishes during the early 1860s in the South African Republic, or Transvaal, in the area now comprising the Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and North West provinces of South Africa. It began after the British government had recognised trekkers living in the Transvaal as independent in 1854. The Boers divided into numerous political factions. The war ended in 1864, when an armistice treaty was signed under a karee tree south of the site of the later town of Brits.

The QwaQwa National Park is part of the Golden Gate Highlands National Park and the Maloti-Drakensberg Park and comprises the former Bantustan (homeland) of QwaQwa. It is approximately 60 km from Harrismith on the Golden Gate Road (R712) and formed an integral part of the Highlands Treasure Route.

Badger culling in the United Kingdom is permitted under licence, within a set area and timescale, as a way to reduce badger numbers in the hope of controlling the spread of bovine tuberculosis (bTB). Humans can catch bTB, but public health control measures, including milk pasteurisation and the BCG vaccine, mean it is not a significant risk to human health. The disease affects cattle and other farm animals, some species of wildlife including badgers and deer, and some domestic pets such as cats. Geographically, bTB has spread from isolated pockets in the late 1980s to cover large areas of the west and south-west of England and Wales in the 2010s. Some people believe this correlates with the lack of badger control.

Mmanthatisi was the leader of the Tlokwa people during her son's minority from 1813 until 1824. She came to power as the regent for her son, Sekonyela, (Lentsha) following the death of her husband Kgosi Mokotjo. Mmanthatisi was known as a strong, brave and capable leader, both in times of peace and war. She was referred to by her followers as Mosanyane because of her slender body.

The Battle of Naauwpoort Nek refers to a clash between the Trekboers and Basotho warriors on 29 September 1865. Naauwpoort lies immediately to the north of the Free State town of Clarens.

Walter Mazinyo Matitta Phakoa was a prophet, well known amongst the Basotho in the Free State; although he was born a Hlubi. He is well known for healing people through prayer (thapelo) and one of his mysteries was being born with a full set of teeth which disappeared a few days later. His spring in Qwaqwa is still one of the most visited spaces for spiritual healing.

Witsie’s cave is a sacred site in the Free State and is named after the grandson of Chief Seeka of Makholokoe. The cave is largely associated with Makholokoe – a tribe of the Basotho and has a rich history relating to this tribe, as well as the interactions between blacks and Boers in the 1800s. The cave has been claimed by Makholokoe as an important imprint in their history and is an important landmark in the Province.

Paulus Mopeli Mokhachane (1810–1897) was an African military leader. He was half-brother to King Moshoeshoe I. He was instrumental during the wars between the Basotho and the Boers. He moved with his followers to Qwaqwa following disputes over land on the Warden line.

Lebollo la banna is a Sesotho term for male initiation.

Sesotho poetry is a form of artistic expression using the written and spoken word practiced by the Basotho people in Southern Africa. Written poetry in the Sesotho language has existed for over 150 years however, the oral poetry has been practiced throughout Basotho history.

Stephen Pule Phohlela is a South African politician. Formerly a politician in Qwaqwa and the founder of Thebe-e-Ntsho, he represented the African National Congress (ANC) in the National Assembly for two terms from 1994 to 2004.