The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby went into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

Carrie Chapman Catt was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1900 to 1904 and 1915 to 1920. She founded the League of Women Voters in 1920 and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904, which was later named International Alliance of Women. She "led an army of voteless women in 1919 to pressure Congress to pass the constitutional amendment giving them the right to vote and convinced state legislatures to ratify it in 1920". She "was one of the best-known women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century and was on all lists of famous American women."

Mary Jane (Whitely) Coggeshall was an American suffragist known as the "mother of woman suffrage in Iowa". She was inducted into the Iowa Women's Hall of Fame in 1990.

Antoinette "Nettie" Rogers Shuler (1862–1939) was an American suffragist and author.

Anna Beulah Boyd Ritchie was a founding member of the Fairmont Woman Suffrage Club, third president of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, and officer in the West Virginia Woman's Christian Temperance Union.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Montana. The fight for women's suffrage in Montana started earlier, before even Montana became a state. In 1887, women gained the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues. In the years that followed, women battled for full, equal suffrage, which culminated in a year-long campaign in 1914 when they became one of eleven states with equal voting rights for most women. Montana ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on August 2, 1919 and was the thirteenth state to ratify. Native American women voters did not have equal rights to vote until 1924.

The women's suffrage movement in Montana started while it was still a territory. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was an early organizer that supported suffrage in the state, arriving in 1883. Women were given the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues in 1887. When the state constitutional convention was held in 1889, Clara McAdow and Perry McAdow invited suffragist Henry Blackwell to speak to the delegates about equal women's suffrage. While that proposition did not pass, women retained their right to vote in school and tax elections as Montana became a state. In 1895, National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) came to Montana to organize local groups. Montana suffragists held a convention and created the Montana Woman's Suffrage Association (MWSA). Suffragists continued to organize, hold conventions and lobby the Montana Legislature for women's suffrage through the end of the nineteenth century. In the early twentieth century, Jeannette Rankin became a driving force around the women's suffrage movement in Montana. By January 1913, a women's suffrage bill had passed the Montana Legislature and went out as a referendum. Suffragists launched an all-out campaign leading up to the vote. They traveled throughout Montana giving speeches and holding rallies. They sent out thousands of letters and printed thousands of pamphlets and journals to hand out. Suffragists set up booths at the Montana State Fair and they held parades. Finally, after a somewhat contested election on November 3, 1914, the suffragists won the vote. Montana became one of eleven states with equal suffrage for most women. When the Nineteenth Amendment was passed, Montana ratified it on August 2, 1919. It wasn't until 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act that Native American women gained the right to vote.

Women's suffrage began in Illinois began in the mid-1850s. The first women's suffrage group was formed in Earlville, Illinois, by the cousin of Susan B. Anthony, Susan Hoxie Richardson. After the Civil War, former abolitionist Mary Livermore organized the Illinois Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), which would later be renamed the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA). Frances Willard and other suffragists in the IESA worked to lobby various government entities for women's suffrage. In the 1870s, women were allowed to serve on school boards and were elected to that office. The first women to vote in Illinois were 15 women in Lombard, Illinois, led by Ellen A. Martin, who found a loophole in the law in 1891. Women were eventually allowed to vote for school offices in the 1890s. Women in Chicago and throughout Illinois fought for the right to vote based on the idea of no taxation without representation. They also continued to expand their efforts throughout the state. In 1913, women in Illinois were successful in gaining partial suffrage. They became the first women east of the Mississippi River to have the right to vote in presidential elections. Suffragists then worked to register women to vote. Both African-American and white suffragists registered women in huge numbers. In Chicago alone 200,000 women were registered to vote. After gaining partial suffrage, women in Illinois kept working towards full suffrage. The state became the first to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, passing the ratification on June 10, 1919. The League of Women Voters (LWV) was announced in Chicago on February 14, 1920.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Illinois. Women's suffrage in Illinois began in the mid 1850s. The first women's suffrage group was created in 1855 in Earlville, Illinois by Susan Hoxie Richardson. The Illinois Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), later renamed the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA), was created by Mary Livermore in 1869. This group held annual conventions and petitioned various governmental bodies in Illinois for women's suffrage. On June 19, 1891, women gained the right to vote for school offices. However, it wasn't until 1913 that women saw expanded suffrage. That year women in Illinois were granted the right to vote for Presidential electors and various local offices. Suffragists continued to fight for full suffrage in the state. Finally, Illinois became the first state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment on June 10, 1919. The League of Women Voters (LWV) was announced in Chicago on February 14, 1920.

Early women's suffrage work in Alabama started in the 1860s. Priscilla Holmes Drake was the driving force behind suffrage work until the 1890s. Several suffrage groups were formed, including a state suffrage group, the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO). The Alabama Constitution had a convention in 1901 and suffragists spoke and lobbied for women's rights provisions. However, the final constitution continued to exclude women. Women's suffrage efforts were mainly dormant until the 1910s when new suffrage groups were formed. Suffragists in Alabama worked to get a state amendment ratified and when this failed, got behind the push for a federal amendment. Alabama did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1953. For many years, both white women and African American women were disenfranchised by poll taxes. Black women had other barriers to voting including literacy tests and intimidation. Black women would not be able to fully access their right to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Women's suffrage began in Delaware the late 1860s, with efforts from suffragist, Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, and an 1869 women's rights convention held in Wilmington, Delaware. Stuart, along with prominent national suffragists lobbied the Delaware General Assembly to amend the state constitution in favor of women's suffrage. Several suffrage groups were formed early on, but the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) formed in 1896, would become one of the major state suffrage clubs. Suffragists held conventions, continued to lobby the government and grow their movement. In 1913, a chapter of the Congressional Union (CU), which would later be known at the National Woman's Party (NWP), was set up by Mabel Vernon in Delaware. NWP advocated more militant tactics to agitate for women's suffrage. These included picketing and setting watchfires. The Silent Sentinels protested in Washington, D.C., and were arrested for "blocking traffic." Sixteen women from Delaware, including Annie Arniel and Florence Bayard Hilles, were among those who were arrested. During World War I, both African-American and white suffragists in Delaware aided the war effort. During the ratification process for the Nineteenth Amendment, Delaware was in the position to become the final state needed to complete ratification. A huge effort went into persuading the General Assembly to support the amendment. Suffragists and anti-suffragists alike campaigned in Dover, Delaware for their cause. However, Delaware did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until March 6, 1923, well after it was already part of the United States Constitution.

Women's suffrage began in Nevada began in the late 1860s. Lecturer and suffragist Laura de Force Gordon started giving women's suffrage speeches in the state starting in 1867. In 1869, Assemblyman Curtis J. Hillyer introduced a women's suffrage resolution in the Nevada Legislature. He also spoke out on women's rights. Hillyer's resolution passed, but like all proposed amendments to the state constitution, must pass one more time and then go out to a voter referendum. In 1870, Nevada held its first women's suffrage convention in Battle Mountain Station. In the late 1880s, women gained the right to run for school offices and the next year several women are elected to office. A few suffrage associations were formed in the mid 1890s, with a state group operating a few women's suffrage conventions. However, after 1899, most suffrage work slowed down or stopped altogether. In 1911, the Nevada Equal Franchise Society (NEFS) was formed. Attorney Felice Cohn wrote a women's suffrage resolution that was accepted and passed the Nevada Legislature. The resolution passed again in 1913 and will go out to the voters on November 3, 1914. Suffragists in the state organized heavily for the 1914 vote. Anne Henrietta Martin brought in suffragists and trade unionists from other states to help campaign. Martin and Mabel Vernon traveled around the state in a rented Ford Model T, covering thousands of miles. Suffragists in Nevada visited mining towns and even went down into mines to talk to voters. On November 3, the voters of Nevada voted overwhelmingly for women's suffrage. Even though Nevada women won the vote, they did not stop campaigning for women's suffrage. Nevada suffragists aided other states' campaigns and worked towards securing a federal suffrage amendment. On February 7, 1920, Nevada became the 28th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

The first women's suffrage effort in Florida was led by Ella C. Chamberlain in the early 1890s. Chamberlain began writing a women's suffrage news column, started a mixed-gender women's suffrage group and organized conventions in Florida.

The movement for women's suffrage in Arizona began in the late 1800s. After women's suffrage was narrowly voted down at the 1891 Arizona Constitutional Convention, prominent suffragettes such as Josephine Brawley Hughes and Laura M. Johns formed the Arizona Suffrage Association and began touring the state campaigning for women's right to vote. Momentum built throughout the decade, and after a strenuous campaign in 1903, a woman's suffrage bill passed both houses of the legislature but was ultimately vetoed by Governor Alexander Oswald Brodie.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Arizona. The first women's suffrage bill was brought forward in the Arizona Territorial legislature in 1883, but it did not pass. Suffragists worked to influence the Territorial Constitutional Convention in 1891 but lost by only three votes. That year, the Arizona Suffrage Association was formed. In 1897, taxpaying women gained the right to vote in school board elections. Suffragists from both Arizona and around the country continued to lobby the territorial legislature and organize women's suffrage groups. In 1903, a women's suffrage bill passed, but it was vetoed by the governor. In 1910, suffragists worked to influence the Arizona State Constitutional Convention, but were again unsuccessful. When Arizona became a state on February 14, 1912, an attempt to legislate a women's suffrage amendment to the Arizona Constitution failed. Frances Munds mounted a successful ballot initiative campaign. On November 5, 1912, women's suffrage passed in Arizona. In 1913, the voter registration books were opened to women. In 1914, women participated in their first primary elections. Arizona ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 12, 1920. However, Native American women and Latinas would wait longer for full voting rights.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Maine. Suffragists began campaigning in Maine in the mid 1850s. A lecture series was started by Ann F. Jarvis Greely and other women in Ellsworth, Maine in 1857. The first women's suffrage petition to the Maine Legislature was sent that same year. Women continue to fight for equal suffrage throughout the 1860s and 1870s. The Maine Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) is established in 1873 and the next year, the first Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) chapter was started. In 1887, the Maine Legislature votes on a women's suffrage amendment to the state constitution, but it does not receive the necessary two-thirds vote. Additional attempts to pass women's suffrage legislation receives similar treatment throughout the rest of the century. In the twentieth century, suffragists continue to organize and meet. Several suffrage groups form, including the Maine chapter of the College Equal Suffrage League in 1914 and the Men's Equal Suffrage League of Maine in 1914. In 1917, a voter referendum on women's suffrage is scheduled for September 10, but fails at the polls. On November 5, 1919 Maine ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment. On September 13, 1920, most women in Maine are able to vote. Native Americans in Maine are barred from voting for many years. In 1924, Native Americans became American citizens. In 1954, a voter referendum for Native American voting rights passes. The next year, Lucy Nicolar Poolaw (Penobscot), is the Native American living on an Indian reservation to cast a vote.

Attempts to secure women's suffrage in Wisconsin began before the Civil War. In 1846, the first state constitutional convention delegates for Wisconsin discussed women's suffrage and the final document eventually included a number of progressive measures. This constitution was rejected and a more conservative document was eventually adopted. Wisconsin newspapers supported women's suffrage and Mathilde Franziska Anneke published the German language women's rights newspaper, Die Deutsche Frauen-Zeitung, in Milwaukee in 1852. Before the war, many women's rights petitions were circulated and there was tentative work in forming suffrage organizations. After the Civil War, the first women's suffrage conference held in Wisconsin took place in October 1867 in Janesville. That year, a women's suffrage amendment passed in the state legislature and waited to pass the second year. However, in 1868 the bill did not pass again. The Wisconsin Woman Suffrage Association (WWSA) was reformed in 1869 and by the next year, there were several chapters arranged throughout Wisconsin. In 1884, suffragists won a brief victory when the state legislature passed a law to allow women to vote in elections on school-related issues. On the first voting day for women in 1887, the state Attorney General made it more difficult for women to vote and confusion about the law led to court challenges. Eventually, it was decided that without separate ballots, women could not be allowed to vote. Women would not vote again in Wisconsin until 1902 after separate school-related ballots were created. In the 1900s, state suffragists organized and continued to petition the Wisconsin legislature on women's suffrage. By 1911, two women's suffrage groups operated in the state: WWSA and the Political Equality League (PEL). A voter referendum went to the public in 1912. Both WWSA and PEL campaigned hard for women's equal suffrage rights. Despite the work put in by the suffragists, the measure failed to pass. PEL and WWSA merged again in 1913 and women continued their education work and lobbying. By 1915, the National Woman's Party also had chapters in Wisconsin and several prominent suffragists joined their ranks. The National Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was also very present in Wisconsin suffrage efforts. Carrie Chapman Catt worked hard to keep Wisconsin suffragists on the path of supporting a federal woman's suffrage amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Wisconsin an hour behind Illinois on June 10, 1919. However, Wisconsin was the first to turn in the ratification paperwork to the State Department.

Marjorie Shuler was an American publicist and author for the woman suffragists from New York. She wrote for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) major publication, The Woman Citizen and was the author of several books about suffrage and voting, including The Woman Voter's Manual (1918) and one of the very few novels about suffrage, For Rent -- One Pedestal (1917). She was the daughter of Antoinette Nettie Rogers Shuler, a well known suffragist and one of the founders of NAWSA. Additionally, Shuler wrote a memoir of her flying trip around the world, the first ever by a woman, titled A Passenger to Adventure.

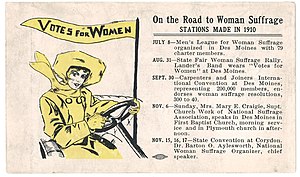

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Iowa. Women's suffrage work started early in Iowa's history. Organizing began in the late 1860s with the first state suffrage convention taking place in 1870. In the 1890s, women gained the right to vote on municipal bonds, tax efforts and school-related issues. By 1916, a state suffrage amendment went to out to a voter referendum, which failed. Iowa was the tenth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment in 1919.