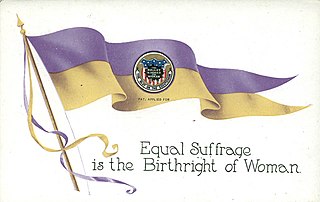

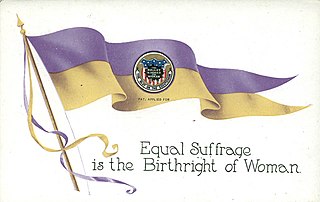

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby went into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

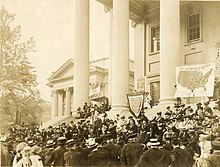

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Carrie Chapman Catt was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1900 to 1904 and 1915 to 1920. She founded the League of Women Voters in 1920 and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904, which was later named International Alliance of Women. She "led an army of voteless women in 1919 to pressure Congress to pass the constitutional amendment giving them the right to vote and convinced state legislatures to ratify it in 1920". She "was one of the best-known women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century and was on all lists of famous American women."

Women's suffrage, or the right of women to vote, was established in the United States over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, first in various states and localities, then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Lila Meade Valentine was a Virginia education reformer, health-care advocate, and one of the main leaders of her state's participation in the woman's suffrage movement in the United States. She worked to improve public education through her co-founding and leadership of the Richmond Education Association, and advocated for public health by founding the Instructive Visiting Nurses Association, through which she helped eradicate tuberculosis from the Richmond area.

Emma Smith DeVoe was an American women suffragist in the early twentieth century, changing the face of politics for both women and men alike. When she died, the Tacoma News Tribune called her Washington state's "Mother of Women's Suffrage".

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

The Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) was an organization founded in 1903 to support white women's suffrage in Texas. It was originally formed under the name of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) and later renamed in 1916. TESA did allow men to join. TESA did not allow black women as members, because at the time to do so would have been "political suicide." The El Paso Colored Woman's Club applied for TESA membership in 1918, but the issue was deflected and ended up going nowhere. TESA focused most of their efforts on securing the passage of the federal amendment for women's right to vote. The organization also became the state chapter of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). After women earned the right to vote, TESA reformed as the Texas League of Women Voters.

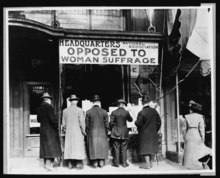

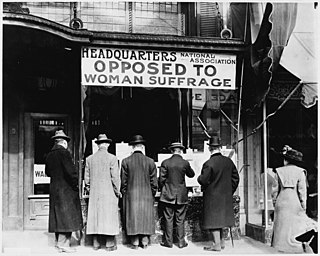

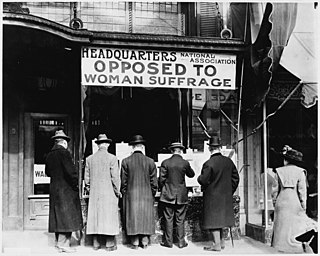

The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded in the United States by women opposed to the suffrage movement in 1911. It was the most popular anti-suffrage organization in northeastern cities. NAOWS had influential local chapters in many states, including Texas and Virginia.

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was founded in 1909 in Richmond, Virginia. Like many similar organizations in other states, the league's goal was to secure voting rights for women. When the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1920, enabling women to vote in all states, the Equal Suffrage League dissolved and was reconstituted as Virginia League of Women Voters, associated with the national League of Women Voters. The 19th Amendment was not ratified in Virginia until 1952.

Anna Whitehead Bodeker was an American suffragist who led the earliest attempt to organize for women's suffrage in the state of Virginia. Bodeker brought national leaders of the women's suffrage movement to Richmond, Virginia to speak; published newspaper articles to draw attention and supporters to the cause; and helped found the Virginia State Woman Suffrage Association in 1870, the first suffrage association in the state.

The women's suffrage movement began in California in the 19th century and was successful with the passage of Proposition 4 on October 10, 1911. Many of the women and men involved in this movement remained politically active in the national suffrage movement with organizations such as the National American Women's Suffrage Association and the National Woman's Party.

Orra Henderson Moore Gray Langhorne was an American writer, reformer, and an early supporter and activist for women's suffrage in Virginia. Langhorne held progressive views for her time, often writing in favor of racial reconciliation, improved educational opportunities for African Americans, and women's rights. She founded the Virginia Suffrage Society, one of the first women's suffrage organizations in the state of Virginia.

The Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference was a group dedicated to winning voting rights for white women. The group consisted mainly of highly educated, middle and upper class white women of prominent families. They were originally part of the larger National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but broke off in 1906. Prominent leaders in the group included Laura Clay and Kate Gordon, who supported and focused on local and state reforms rather than a national amendment. The group applied tactics like the Lost Cause, the belief that the Confederate cause was moral and just, and the Southern strategy, which appealed to white voters by promoting racism.

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis was the founder of the Lynchburg Equal Suffrage League and vice-president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. She was also one of the founders of the Virginia League of Women Voters.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Missouri. Women's suffrage in Missouri started in earnest after the Civil War. In 1867, one of the first women's suffrage groups in the U.S. was formed, called the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri. Suffragists in Missouri held conventions, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly and challenged the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). The case that went to SCOTUS in 1874, Minor v. Happersett was not ruled in the suffragists' favor. Instead of challenging the courts for suffrage, Missouri suffragists continued to lobby for changes in legislation. In April 1919, they gained the right to vote in presidential elections. On July 3, 1919, Missouri becomes the eleventh state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

The women's suffrage movement was active in Missouri mostly after the Civil War. There were significant developments in the St. Louis area, though groups and organized activity took place throughout the state. An early suffrage group, the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri, was formed in 1867, attracting the attention of Susan B. Anthony and leading to news items around the state. This group, the first of its kind, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly for women's suffrage and established conventions. In the early 1870s, many women voted or registered to vote as an act of civil disobedience. The suffragist Virginia Minor was one of these women when she tried to register to vote on October 15, 1872. She and her husband, Francis Minor, sued, leading to a Supreme Court case that asserted the Fourteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote. The case, Minor v. Happersett, was decided against the Minors and led suffragists in the country to pursue legislative means to grant women suffrage.

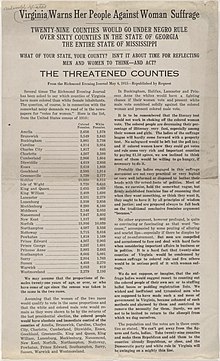

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Virginia. While there were some very early efforts to support women's suffrage in Virginia, most of the activism for the vote for women occurred early in the 20th century. The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was formed in 1909 and the Virginia Branch of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage was formed in 1915. Over the next years, women held rallies, conventions and many propositions for women's suffrage were introduced in the Virginia General Assembly. Virginia didn't ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952. Native American women could not have a full vote until 1924 and African American women were effectively disenfranchised until the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965.

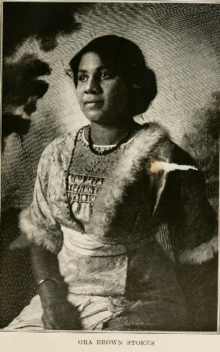

The first women's suffrage group in Georgia, the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association (GWSA), was formed in 1892 by Helen Augusta Howard. Over time, the group, which focused on "taxation without representation" grew and earned the support of both men and women. Howard convinced the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) to hold their first convention outside of Washington, D.C., in 1895. The convention, held in Atlanta, was the first large women's rights gathering in the Southern United States. GWSA continued to hold conventions and raise awareness over the next years. Suffragists in Georgia agitated for suffrage amendments, for political parties to support white women's suffrage and for municipal suffrage. In the 1910s, more organizations were formed in Georgia and the number of suffragists grew. In addition, the Georgia Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage also formed an organized anti-suffrage campaign. Suffragists participated in parades, supported bills in the legislature and helped in the war effort during World War I. In 1917 and 1919, women earned the right to vote in primary elections in Waycross, Georgia and in Atlanta respectively. In 1919, after the Nineteenth Amendment went out to the states for ratification, Georgia became the first state to reject the amendment. When the Nineteenth Amendment became the law of the land, women still had to wait to vote because of rules regarding voter registration. White Georgia women would vote statewide in 1922. Native American women and African-American women had to wait longer to vote. Black women were actively excluded from the women's suffrage movement in the state and had their own organizations. Despite their work to vote, Black women faced discrimination at the polls in many different forms. Georgia finally ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on February 20, 1970.

Early women's suffrage work in Alabama started in the 1860s. Priscilla Holmes Drake was the driving force behind suffrage work until the 1890s. Several suffrage groups were formed, including a state suffrage group, the Alabama Woman Suffrage Organization (AWSO). The Alabama Constitution had a convention in 1901 and suffragists spoke and lobbied for women's rights provisions. However, the final constitution continued to exclude women. Women's suffrage efforts were mainly dormant until the 1910s when new suffrage groups were formed. Suffragists in Alabama worked to get a state amendment ratified and when this failed, got behind the push for a federal amendment. Alabama did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1953. For many years, both white women and African American women were disenfranchised by poll taxes. Black women had other barriers to voting including literacy tests and intimidation. Black women would not be able to fully access their right to vote until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.