Ayahuasca is a South American psychoactive beverage, traditionally used by Indigenous cultures and folk healers in the Amazon and Orinoco basins for spiritual ceremonies, divination, and healing a variety of psychosomatic complaints.

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spirits or spiritual energies into the physical world for the purpose of healing, divination, or to aid human beings in some other way.

Entheogens are psychoactive substances, including psychedelic drugs used throughout history in sacred contexts.

A curandero is a traditional native healer or shaman found primarily in Latin America and also in the United States. A curandero is a specialist in traditional medicine whose practice can either contrast with or supplement that of a practitioner of Western medicine. A curandero is claimed to administer shamanistic and spiritistic remedies for mental, emotional, physical and spiritual illnesses. Some curanderos, such as Don Pedrito, the Healer of Los Olmos, make use of simple herbs, waters, or mud to allegedly effect their cures. Others add Catholic elements, such as holy water and pictures of saints; San Martin de Porres for example is heavily employed within Peruvian curanderismo. The use of Catholic prayers and other borrowings and lendings is often found alongside native religious elements. Many curanderos emphasize their native spirituality in healing while being practicing Catholics. Still others, such as Maria Sabina, employ hallucinogenic media and many others use a combination of methods. Most of the concepts related to curanderismo are Spanish words, often with medieval, vernacular definitions.

Pablo Cesar Amaringo Shuña was a Peruvian artist, renowned for his intricate, colourful depictions of his visions from drinking the entheogenic plant brew ayahuasca. He was first brought to the West's attention by Dennis McKenna and Luis Eduardo Luna, who met Pablo in Pucallpa while traveling during work on an ethnobotanical project. Pablo worked as a vegetalista, a shaman in the mestizo tradition of healing, for many years; up to his death, he painted, helped run the Usko-Ayar school of painting, and supervised ayahuasca retreats.

Jeremy Narby is a Canadian anthropologist and author.

Neoshamanism, refers to new forms of shamanism, where it usually means shamanism practiced by Western people as a type of New Age spirituality, without a connection to traditional shamanic societies. It is sometimes also used for modern shamanic rituals and practices which, although they have some connection to the traditional societies in which they originated, have been adapted somehow to modern circumstances. This can include "shamanic" rituals performed as an exhibition, either on stage or for shamanic tourism, as well as modern derivations of traditional systems that incorporate new technology and worldviews.

Santo Daime is a universalistic/syncretic religion founded in the 1930s in the Brazilian Amazonian state of Acre based on the teachings of Raimundo Irineu Serra, known as Mestre Irineu. Santo Daime incorporates elements of several religious or spiritual traditions, mainly Folk Catholicism, Kardecist Spiritism, African animism and indigenous South American shamanism, including vegetalismo.

Luis Eduardo Luna is an anthropologist and noted ayahuasca researcher.

Icaro is a South American indigenous and mestizo colloquialism for magic song. Today, this term is commonly used to describe the medicine songs performed in vegetal ceremonies, especially by shamans in ayahuasca ceremonies.

Chakapa is a Quechua word for a shaker or rattle constructed of bundled leaves. Bushes of the genus Pariana provide the leaves for the chakapa. Chakapa is also the common name for these bushes.

The Jivaroan peoples are the indigenous peoples in the headwaters of the Marañon River and its tributaries, in northern Peru and eastern Ecuador. The tribes speak the Chicham languages.

Amazonian Kichwas are a grouping of indigenous Kichwa peoples in the Ecuadorian Amazon, with minor groups across the borders of Colombia and Peru. Amazonian Kichwas consists of different ethnic peoples, including Napo Kichwa and Canelos Kichwa. There are approximately 419 organized communities of the Amazonian Kichwas. The basic socio-political unit is the ayllu. The ayllus in turn constitute territorial clans, based on common ancestry. Unlike other subgroups, the Napo Kichwa maintain less ethnic duality of acculturated natives or Christians.

Vegetalismo is a term used to refer to a practice of mestizo shamanism in the Peruvian Amazon in which the shamans—known as vegetalistas—are said to gain their knowledge and power to cure from the vegetales, or plants of the region. Many believe to receive their knowledge from ingesting the hallucinogenic, emetic brew ayahuasca.

Tsentsak are invisible pathogenic projectiles or magical darts utilized in indigenous and mestizo shamanic practices for the purposes of sorcery and healing throughout much the Amazon Basin. Anthropologists identify them as objects referenced in emic accounts that represent indigenous beliefs. Tsentak are not recognized in scientific medicine.

The Yacuruna are a mythical water people of the Amazon basin who live in beautiful underwater cities, often at the mouths of rivers. Belief in the Yacuruna is most prominently found among indigenous people of the Amazon. The term is derived from the Quechua language, yaku ("water") and runa ("man").

Tsunki is a name for the primordial spirit shaman within the Achuar and Shuar people of Amazonia. The term is derived from the Jivaroan language family. It translates to English as "the first shaman" and is frequently alluded to in shamanic songs.

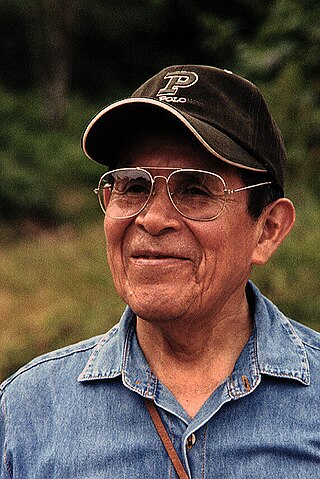

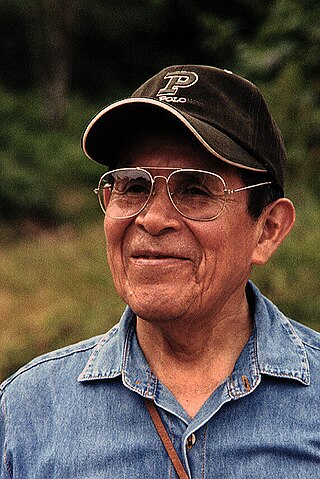

Guillermo Arévalo Valera is a Shipibo vegetalista and businessperson from the Maynas Province of Peru. His Shipibo name is Kestenbetsa.

Manuel Córdova-Rios was a vegetalista (herbalist) of the upper Amazon, and the subject of several popular books.

Shamanism is a religious practice present in various cultures and religions around the world. Shamanism takes on many different forms, which vary greatly by region and culture and are shaped by the distinct histories of its practitioners.