Traditional healers of Southern Africa are practitioners of traditional African medicine in Southern Africa. They fulfil different social and political roles in the community like divination, healing physical, emotional, and spiritual illnesses, directing birth or death rituals, finding lost cattle, protecting warriors, counteracting witchcraft and narrating the history, cosmology, and concepts of their tradition.

A curandero is a traditional native healer or shaman found primarily in Latin America and also in the United States. A curandero is a specialist in traditional medicine whose practice can either contrast with or supplement that of a practitioner of Western medicine. A curandero is claimed to administer shamanistic and spiritistic remedies for mental, emotional, physical and spiritual illnesses. Some curanderos, such as Don Pedrito, the Healer of Los Olmos, make use of simple herbs, waters, or mud to allegedly effect their cures. Others add Catholic elements, such as holy water and pictures of saints; San Martin de Porres for example is heavily employed within Peruvian curanderismo. The use of Catholic prayers and other borrowings and lendings is often found alongside native religious elements. Many curanderos emphasize their native spirituality in healing while being practicing Catholics. Still others, such as Maria Sabina, employ hallucinogenic media and many others use a combination of methods. Most of the concepts related to curanderismo are Spanish words, often with medieval, vernacular definitions.

Stories and practices that are considered part of Korean folklore go back several thousand years. These tales derive from a variety of origins, including Shamanism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and more recently Christianity.

A jengu is a water spirit in the traditional beliefs of the Sawabantu groups of Cameroon, like the Duala, Bakweri, Malimba, Subu, Bakoko, Oroko people. Among the Bakweri, the term used is liengu. Miengu are similar to bisimbi in the Bakongo spirituality and Mami Wata. The Bakoko people use the term Bisima.

Filipino shamans, commonly known as babaylan, were shamans of the various ethnic groups of the pre-colonial Philippine islands. These shamans specialized in communicating, appeasing, or harnessing the spirits of the dead and the spirits of nature. They were almost always women or feminized men. They were believed to have spirit guides, by which they could contact and interact with the spirits and deities and the spirit world. Their primary role were as mediums during pag-anito séance rituals. There were also various subtypes of babaylan specializing in the arts of healing and herbalism, divination, and sorcery.

A machi is a traditional healer and religious leader in the Mapuche culture of Chile and Argentina. Machis play significant roles in Mapuche religion. In contemporary Mapuche culture, women are more commonly machis than men, but it is not a rule. Male machi are known as Machi Weye.

The Hmong people are an ethnic group currently native to several countries, believed to have come from the Yangtze river basin area in southern China. The Hmong are known in China as the Miao, which encompasses not only Hmong, but also other related groups such as Hmu, Qo Xiong and A-Hmao. There is debate about usage of this term, especially amongst Hmong living in the West, as it is believed by some to be derogatory, although Hmong living in China still call themselves by this name. Throughout recorded history, the Hmong have remained identifiable as Hmong because they have maintained the Hmong language, customs, and ways of life while adopting the ways of the country in which they live. In the 1960s and 1970s, many Hmong were secretly recruited by the American CIA to fight against communism during the Vietnam War. After American armed forces pulled out of Vietnam the Pathet Lao, a communist regime, took over in Laos and ordered the prosecution and re-education of all those who had fought against its cause during the war. While many Hmong are still left in Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar, and China, since 1975 many Hmong have fled Laos in fear of persecution. Housed in Thai refugee camps during the 1980s, many have resettled in countries such as the United States, French Guiana, Australia, France, Germany, as well as some who have chosen to stay in Thailand in hope of returning to their own land. In the United States, new generations of Hmong are gradually assimilating into American society while being taught Hmong culture and history by their elders. Many fear that as the older generations pass on, the knowledge of the Hmong among Hmong Americans will die as well.

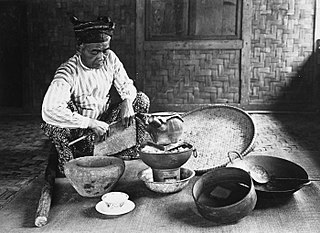

Dukun is an Indonesian term for shaman. Their societal role is that of a traditional healer, spirit medium, custom and tradition experts and on occasion sorcerers and masters of black magic. In common usage the dukun is often confused with another type of shaman, the pawang. It is often mistranslated into English as "witch doctor" or "medicine man". Many self-styled dukun in Indonesia are simply scammers and criminals, preying on people who were raised to believe in the supernatural.

The Kallawaya are an indigenous group living in the Andes of Bolivia. They live in the Bautista Saavedra Province and Muñecas Province of the La Paz Department but are best known for being an itinerant group of traditional healers that travel on foot to reach their patients. According to the UNESCO Safeguarding Project, the Kallawaya can be traced to the pre-Inca period as direct descendants of the Tiwanaku and Mollo cultures, meaning their existence has lasted approximately 1,000 years. They are known to have performed complex procedures like brain surgery alongside their continuous use of medicinal plants as early as 700 AD. Most famously, they are known to have helped to save thousands of lives during the construction of the Panama Canal, in which they used traditional plant remedies to treat the malaria epidemic. Some historical sources even cite the Kallawayas as the first to use quinine to prevent and control malaria. In 2012, there were 11,662 Kallawaya throughout Bolivia.

The Nahua of La Huasteca is an indigenous ethnic group of Mexico and one of the Nahua peoples. They live in the mountainous area called La Huasteca which is located in north eastern Mexico and contains parts of the states of Hidalgo, Veracruz and Puebla. They speak one of the Huasteca Nahuatl dialects: western, central or eastern Huasteca Nahuatl.

The Jivaroan peoples are the indigenous peoples in the headwaters of the Marañon River and its tributaries, in northern Peru and eastern Ecuador. The tribes speak the Chicham languages.

Inca mythology is the universe of legends and collective memory of the Inca civilization, which took place in the current territories of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina, incorporating in the first instance, systematically, the territories of the central highlands of Peru to the north.

Pachamama is a goddess revered by the indigenous peoples of the Andes. In Inca mythology she is an "Earth Mother" type goddess, and a fertility goddess who presides over planting and harvesting, embodies the mountains, and causes earthquakes. She is also an ever-present and independent deity who has her own creative power to sustain life on this earth. Her shrines are hallowed rocks, or the boles of legendary trees, and her artists envision her as an adult female bearing harvests of potatoes or coca leaves. The four cosmological Quechua principles – Water, Earth, Sun, and Moon – claim Pachamama as their prime origin. Priests sacrifice offerings of llamas, cuy, and elaborate, miniature, burned garments to her. Pachamama is the mother of Inti the sun god, and Mama Killa the moon goddess. Mama Killa is said to be the wife of Inti.

Vegetalismo is a term used to refer to a practice of mestizo shamanism in the Peruvian Amazon in which the shamans—known as vegetalistas—are said to gain their knowledge and power to cure from the vegetales, or plants of the region. Many believe to receive their knowledge from ingesting the hallucinogenic, emetic brew ayahuasca.

Pulingaws are known as shamans for the Taiwanese indigenous peoples of Puyuma and Paiwan, which in general would share the same roles as the Puyuman pulingaw with some distinctions. Pulingaws are, claimed to be, selected by their electing ancestors known as kinitalian, who often turn out to be the pulingaws' ancestors, which happen to also be another form of spiritual entity called birua. Kinitalians can choose whoever they please as the next pulingaw amongst its immediate or extended family members. Although females were often selected to continue the line of shaman-ism, not all pulingaws are female and there were rare instances where males were selected to take up the role. However, the pulingaw's gender issue is still an ongoing debate as certain sources insist that only females become pulingaws. The pulingaws are considered as therapists, who are responsible for mediating and bringing peace to social and biological disorders. They are also responsible for various rituals that range from hunting ceremonies, exorcisms and funerals.

Kev Dab Kev Qhuas is the common ethnic religion of the Miao people, best translated as the "practice of spirituality". The religion is also called Hmongism by a Hmong American church established in 2012 to organize it among Hmong people in the United States.

Mu (Korean: 무) is the Korean term for a shaman in Korean shamanism. Korean shamans hold rituals called gut for the welfare of the individuals and society.

Shamanism is a religious practice present in various cultures and religions around the world. Shamanism takes on many different forms, which vary greatly by region and culture and are shaped by the distinct histories of its practitioners.

The mengdu, also called the three mengdu and the three mengdu of the sun and moon, are a set of three kinds of brass ritual devices—a pair of knives, a bell, and divination implements—which are the symbols of shamanic priesthood in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. Although similar ritual devices are found in mainland Korea, the religious reverence accorded to the mengdu is unique to Jeju.

The Durin-gut, also called the Michin-gut and the Chuneun-gut, is the healing ceremony for mental illnesses in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. While commonly held as late as the 1980s, it has now become very rare due to the introduction of modern psychiatry.