Related Research Articles

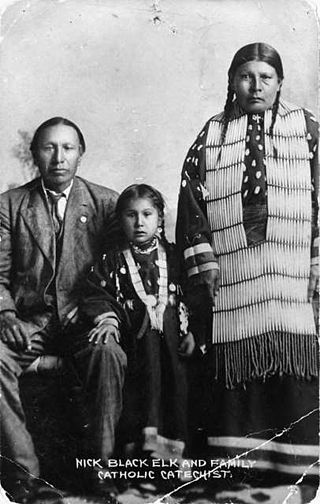

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk, was a wičháša wakȟáŋ and heyoka of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and fought with him in the Battle of Little Bighorn. He survived the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. He toured and performed in Europe as part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West.

White Buffalo Calf Woman or White Buffalo Maiden is a sacred woman of supernatural origin, central to the Lakota religion as the primary cultural prophet. Oral traditions relate that she brought the "Seven Sacred Rites" to the Lakota people.

A vision quest is a rite of passage in some Native American cultures. It is usually only undertaken by young males entering adulthood. Individual Indigenous cultures have their own names for their rites of passage. "Vision quest" is an English-language umbrella term, and may not always be accurate or used by the cultures in question.

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individuals make personal sacrifices on behalf of the community.

Frank Fools Crow was an Oglala Lakota civic and religious leader. 'Grandfather', or 'Grandpa Frank' as he was often called, was a nephew of Black Elk who worked to preserve Lakota traditions, including the Sun Dance and yuwipi ceremonies. He supported Lakota sovereignty and treaty rights, and was a leader of the traditional faction during the armed standoff at Wounded Knee in 1973. With writer Thomas E. Mails, he produced two books about his life and work, Fools Crow in 1979, and Fools Crow: Wisdom and Power in 1990.

Plastic shamans, or plastic medicine people, is a pejorative colloquialism applied to individuals who are attempting to pass themselves off as shamans, holy people, or other traditional spiritual leaders, but who have no genuine connection to the traditions or cultures they claim to represent. In some cases, the "plastic shaman" may have some genuine cultural connection, but is seen to be exploiting that knowledge for ego, power, or money.

The traditional beliefs and practices of African people are highly diverse, including various ethnic religions. Generally, these traditions are oral rather than scriptural and are passed down from one generation to another through folk tales, songs, and festivals, and include beliefs in spirits and higher and lower gods, sometimes including a supreme being, as well as the veneration of the dead, and use of magic and traditional African medicine. Most religions can be described as animistic with various polytheistic and pantheistic aspects. The role of humanity is generally seen as one of harmonizing nature with the supernatural.

Joseph Epes Brown was an American scholar whose lifelong dedication to Native American traditions helped to bring the study of American Indian religious traditions into higher education. His seminal work was a book entitled, The Sacred Pipe, an account of his discussions with the Lakota holy man, Black Elk, regarding the religious rites of his people.

Čhetáŋ Sápa' (Black Hawk) (c. 1832 – c. 1890) was a medicine man and member of the Sans Arc or Itázipčho band of the Lakota people. He is most known for a series of 76 drawings that were later bound into a ledger book that depicts scenes of Lakota life and rituals. The ledger drawings were commissioned by William Edward Canton, a federal "Indian trader" at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. Black Hawk's drawings were drawn between 1880-1881. Today they are known as one of the most complete visual records of Lakota cosmology, ritual and daily life.

In the culture of the San, an indigenous people of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Angola, healers administer a wide range of practices, from oral remedies containing plant and animal material, making cuts on the body and rubbing in 'potent' substances, inhaling smoke of smouldering organic matter like certain twigs or animal dung, wearing parts of animals or 'jewellery' that 'makes them strong.' Anecdotal records reveal that the Khoikhoi and San people have used Sceletium tortuosum since ancient times as an essential part of the indigenous culture and materia mediac. The trance dance is one of the most distinctive features of San culture.

Ghost sickness is a cultural belief among some traditional indigenous peoples in North America, notably the Navajo, and some Muscogee and Plains cultures, as well as among Polynesian peoples. People who are preoccupied and/or consumed by the deceased are believed to suffer from ghost sickness. Reported symptoms can include general weakness, loss of appetite, suffocation feelings, recurring nightmares, and a pervasive feeling of terror. The sickness is attributed to ghosts or, occasionally, to witches or witchcraft.

A sacred bundle or a medicine bundle is a wrapped collection of sacred items, held by a designated carrier, used in Indigenous American ceremonial cultures.

Leonard Crow Dog was a medicine man and spiritual leader who became well known during the Lakota takeover of the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1973, known as the Wounded Knee Incident. Through his writings and teachings, he has sought to unify Indian people of all nations. As a practitioner of traditional herbal medicine and a leader of Sun Dance ceremonies, Crow Dog was also dedicated to keeping Lakota traditions alive.

Bantu mythology is the system of beliefs and legends of the Bantu people of Africa. Although Bantu peoples account for several hundred different ethnic groups, there is a high degree of homogeneity in Bantu cultures and customs, just as in Bantu languages. Many Bantu cultures traditionally believed in a supreme god whose name is a variation of Nyambe/Nzambe.

Navajo medicine covers a range of traditional healing practices of the Indigenous American Navajo people. It dates back thousands of years as many Navajo people have relied on traditional medicinal practices as their primary source of healing. However, modern day residents within the Navajo Nation have incorporated contemporary medicine into their society with the establishment of Western hospitals and clinics on the reservation over the last century.

Wocekiye is a Lakota language term meaning "to call on for aid," "to pray," and "to claim relationship with". It refers to a practice among Lakota people engaged in both the traditional Lakota religion as well as forms of Christianity.

Shaking tent ceremony is a ritual of some of the indigenous people in North America that is used to connect the people with the spirit realm and establish a connection and line of communication between the spirit world and the mortal world. These ceremonies require special tents or lodges to be made, and are performed under the direction of a shaman, or spiritual leader, who uses different practices, rituals, and materials to perform the ceremony. This ceremony is more commonly used by specific indigenous tribes long ago but is still practiced around the continent today.

The Sitting Bull Crystal Cavern Dance Pavilion is a historic event venue on the south side of U.S. Highway 16 northeast of Rockerville, South Dakota. Built in 1934, it hosted the Duhamel Sioux Indian Pageant, a Lakota tourist performance created by Black Elk in 1927. The pageant ran every summer until its discontinuation in 1957. A major attraction in the 1930s, its purpose was to not only profit off of tourism to the nearby Black Hills and Mount Rushmore but also—according to Black Elk—to represent Lakota traditions in a respectful, authentic way. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1995 as a venue of enduring cultural and religious significance, and for its association with Black Elk.

Lakota religion or Lakota spirituality is the traditional Native American religion of the Lakota people. It is practiced primarily in the Lakota reservations of the North American Plains. The tradition has no formal leadership and displays much internal variation.

References

- ↑ Yuwipi, vision and experience in Oglala ritual by William K. Powers, University of Nebraska Press, 1984

- 1 2 3 American Indian Religious Traditions: An Encyclopedia, Volume 2 by Suzanne J. Crawford, Suzanne J. Crawford O'Brien, Dennis F. Kelley, ABC-CLIO; illustrated edition (June 29, 2005)

- ↑ Pipe, Bible, and Peyote Among the Oglala Lakota: A Study in Religious Identity by Paul B. Steinmetz, Syracuse University Press, 1990

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Native American Healing by William S. Lyon, W. W. Norton & Company (March 17, 1998)