Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. According to modern evolutionary biology, all living beings could be descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal common ancestor (LUCA) of all life on Earth,.

Erasmus Robert Darwin was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

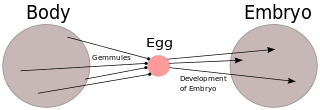

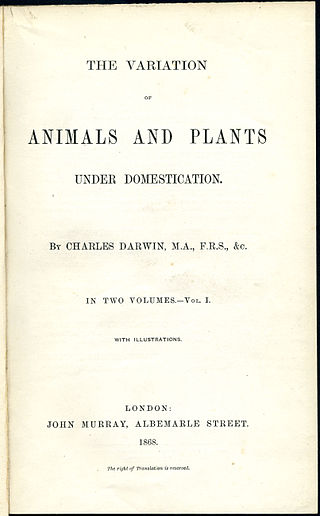

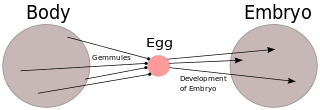

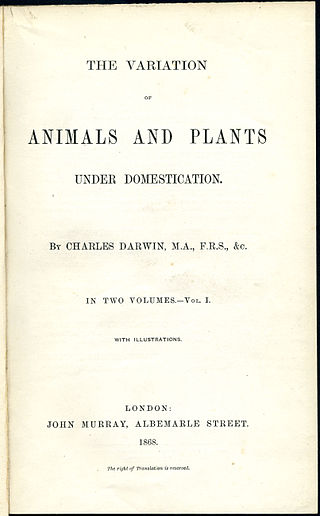

Pangenesis was Charles Darwin's hypothetical mechanism for heredity, in which he proposed that each part of the body continually emitted its own type of small organic particles called gemmules that aggregated in the gonads, contributing heritable information to the gametes. He presented this 'provisional hypothesis' in his 1868 work The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, intending it to fill what he perceived as a major gap in evolutionary theory at the time. The etymology of the word comes from the Greek words pan and genesis ("birth") or genos ("origin"). Pangenesis mirrored ideas originally formulated by Hippocrates and other pre-Darwinian scientists, but using new concepts such as cell theory, explaining cell development as beginning with gemmules which were specified to be necessary for the occurrence of new growths in an organism, both in initial development and regeneration. It also accounted for regeneration and the Lamarckian concept of the inheritance of acquired characteristics, as a body part altered by the environment would produce altered gemmules. This made Pangenesis popular among the neo-Lamarckian school of evolutionary thought. This hypothesis was made effectively obsolete after the 1900 rediscovery among biologists of Gregor Mendel's theory of the particulate nature of inheritance.

On the Origin of Species, published on 24 November 1859, is a work of scientific literature by Charles Darwin that is considered to be the foundation of evolutionary biology. Darwin's book introduced the scientific theory that populations evolve over the course of generations through a process of natural selection. The book presented a body of evidence that the diversity of life arose by common descent through a branching pattern of evolution. Darwin included evidence that he had collected on the Beagle expedition in the 1830s and his subsequent findings from research, correspondence, and experimentation.

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck, often known simply as Lamarck, was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biological evolution occurred and proceeded in accordance with natural laws.

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also called the inheritance of acquired characteristics or more recently soft inheritance. The idea is named after the French zoologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829), who incorporated the classical era theory of soft inheritance into his theory of evolution as a supplement to his concept of orthogenesis, a drive towards complexity.

Thomas Brown was a Scottish philosopher and poet.

The history of zoology before Charles Darwin's 1859 theory of evolution traces the organized study of the animal kingdom from ancient to modern times. Although the concept of zoology as a single coherent field arose much later, systematic study of zoology is seen in the works of Aristotle and Galen in the ancient Greco-Roman world. This work was developed in the Middle Ages by Islamic medicine and scholarship, and in turn their work was extended by European scholars such as Albertus Magnus.

The history of biology traces the study of the living world from ancient to modern times. Although the concept of biology as a single coherent field arose in the 19th century, the biological sciences emerged from traditions of medicine and natural history reaching back to Ayurveda, ancient Egyptian medicine and the works of Aristotle and Galen in the ancient Greco-Roman world. This ancient work was further developed in the Middle Ages by Muslim physicians and scholars such as Avicenna. During the European Renaissance and early modern period, biological thought was revolutionized in Europe by a renewed interest in empiricism and the discovery of many novel organisms. Prominent in this movement were Vesalius and Harvey, who used experimentation and careful observation in physiology, and naturalists such as Linnaeus and Buffon who began to classify the diversity of life and the fossil record, as well as the development and behavior of organisms. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek revealed by means of microscopy the previously unknown world of microorganisms, laying the groundwork for cell theory. The growing importance of natural theology, partly a response to the rise of mechanical philosophy, encouraged the growth of natural history.

Robert Edmond Grant MD FRCPEd FRS FRSE FZS FGS was a British anatomist and zoologist.

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some goal (teleology) due to some internal mechanism or "driving force". According to the theory, the largest-scale trends in evolution have an absolute goal such as increasing biological complexity. Prominent historical figures who have championed some form of evolutionary progress include Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Henri Bergson.

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French Transformisme was a term used by Jean Baptiste Lamarck in 1809 for his theory, and other 18th and 19th century proponents of pre-Darwinian evolutionary ideas included Denis Diderot, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, Erasmus Darwin, Robert Grant, and Robert Chambers, the anonymous author of the book Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation. Opposition in the scientific community to these early theories of evolution, led by influential scientists like the anatomists Georges Cuvier and Richard Owen, and the geologist Charles Lyell, was intense. The debate over them was an important stage in the history of evolutionary thought and influenced the subsequent reaction to Darwin's theory.

Evolutionary ideas during the periods of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment developed over a time when natural history became more sophisticated during the 17th and 18th centuries, and as the scientific revolution and the rise of mechanical philosophy encouraged viewing the natural world as a machine with workings capable of analysis. But the evolutionary ideas of the early 18th century were of a religious and spiritural nature. In the second half of the 18th century more materialistic and explicit ideas about biological evolution began to emerge, adding further strands in the history of evolutionary thought.

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Church Fathers as well as in medieval Islamic science. With the beginnings of modern biological taxonomy in the late 17th century, two opposed ideas influenced Western biological thinking: essentialism, the belief that every species has essential characteristics that are unalterable, a concept which had developed from medieval Aristotelian metaphysics, and that fit well with natural theology; and the development of the new anti-Aristotelian approach to modern science: as the Enlightenment progressed, evolutionary cosmology and the mechanical philosophy spread from the physical sciences to natural history. Naturalists began to focus on the variability of species; the emergence of palaeontology with the concept of extinction further undermined static views of nature. In the early 19th century prior to Darwinism, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) proposed his theory of the transmutation of species, the first fully formed theory of evolution.

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication is a book by Charles Darwin that was first published in January 1868.

This article considers the history of zoology since the theory of evolution by natural selection proposed by Charles Darwin in 1859.

Giosuè Edoard Sangiovanni was an Italian zoologist, the first professor of comparative anatomy in Italy and an early exponent of evolution.

Henry Freke (1813-1888) was an Irish physician and early evolutionary writer.

Romanticism was an intellectual movement that arose in the late eighteenth century and continued through the nineteenth century. The movement had roots in the arts, literature, and science. Largely conceived as a reaction towards the extreme rationalism of the Enlightenment, it championed expressing emotions through aesthetic and emphasizing the transcendent allure of the natural world.

Evolution has been an important theme in fiction, including speculative evolution in science fiction, since the late 19th century, though it began before Charles Darwin's time, and reflects progressionist and Lamarckist views as well as Darwin's. Darwinian evolution is pervasive in literature, whether taken optimistically in terms of how humanity may evolve towards perfection, or pessimistically in terms of the dire consequences of the interaction of human nature and the struggle for survival. Other themes include the replacement of humanity, either by other species or by intelligent machines.