The recorded history of Haiti began in 1492, when the European captain and explorer Christopher Columbus landed on a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean. The western portion of the island of Hispaniola, where Haiti is situated, was inhabited by the Taíno and Arawakan people, who called their island Ayiti. The island was promptly claimed for the Spanish Crown, where it was named La Isla Española, later Latinized to Hispaniola. By the early 17th century, the French had built a settlement on the west of Hispaniola and called it Saint-Domingue. Prior to the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the economy of Saint-Domingue gradually expanded, with sugar and, later, coffee becoming important export crops. After the war which had disrupted maritime commerce, the colony underwent rapid expansion. In 1767, it exported indigo, cotton and 72 million pounds of raw sugar. By the end of the century, the colony encompassed a third of the entire Atlantic slave trade.

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda, was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture first fought and allied with Spanish forces against Saint-Domingue Royalists, then joined with Republican France, becoming Governor-General-for-life of Saint-Domingue, and lastly fought against Bonaparte's republican troops. As a revolutionary leader, Louverture displayed military and political acumen that helped transform the fledgling slave rebellion into a revolutionary movement. Along with Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Louverture is now known as one of the "Fathers of Haiti".

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was the first Haitian Emperor, and leader of the Haitian Revolution, and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1805 constitution. Initially regarded as governor-general, Dessalines was later named Emperor of Haiti as Jacques I (1804–1806) by generals of the Haitian Revolutionary army and ruled in that capacity until being assassinated in 1806. He spearheaded the resistance against French massacres upon Haitians, and eventually became the architect of the 1804 Haitian Massacre against the remaining French residents of Haiti, including some supporters of the revolution. Alongside Toussaint Louverture, has been referred to as one of the fathers of the nation of Haiti.

Saint-Domingue was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1697 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer specifically to the Spanish-held Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, now the Dominican Republic. The borders between the two were fluid and changed over time until they were finally solidified in the Dominican War of Independence in 1844.

Alexandre Sabès Pétion was the first president of the Republic of Haiti from 1807 until his death in 1818. One of Haiti's founding fathers, Pétion belonged to the revolutionary quartet that also includes Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and his later rival Henri Christophe. Regarded as an excellent artilleryman in his early adulthood, Pétion would distinguish himself as an esteemed military commander with experience leading both French and Haitian troops. The 1802 coalition formed by him and Dessalines against French forces led by Charles Leclerc would prove to be a watershed moment in the decade-long conflict, eventually culminating in the decisive Haitian victory at the Battle of Vertières in 1803.

The Haitian Revolution was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti.

Étienne Polverel (1740–1795) was a French lawyer, aristocrat, and revolutionary. He was a member of the Jacobin club. In 1792, he and Léger Félicité Sonthonax were sent to Saint-Domingue to suppress the slave revolt and to implement the decree of April 4, 1792, that gave equality of rights to all free men, regardless of their color.

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) and the subsequent emancipation of Haiti as an independent state provoked mixed reactions in the United States. Among many white Americans, this led to uneasiness, instilling fears of racial instability on its own soil and possible problems with foreign relations and trade between the two countries. Among enslaved black Americans, it fueled hope that the principles of the recent American Revolution might be realized in their own liberation.

Androcide is a term for the hate crime of systematically killing men, boys, or males in general because of their gender. Not all murders of men are androcides in the same way that not all murders of women are femicides. Androcides often happen during war or genocide. Men and boys are not solely targeted because of abstract or ideological hatred. Rather, male civilians are often targeted during warfare as a way to remove those considered to be potential combatants, and during genocide as a way to destroy the entire community.

The War of Knives, also known as the War of the South, was a civil war from June 1799 to July 1800 between the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture, a black ex-slave who controlled the north of Saint-Domingue, and his adversary André Rigaud, a mixed-race free person of color who controlled the south. Louverture and Rigaud fought over de facto control of the French colony of Saint-Domingue during the war. Their conflict followed the withdrawal of British forces from the colony earlier during the Haitian Revolution. The war resulted in Toussaint taking control of the entirety of Saint-Domingue, and Rigaud fleeing into exile.

The Saint-Domingue expedition was a large French military invasion sent by Napoleon Bonaparte, then First Consul, under his brother-in-law Charles Victor Emmanuel Leclerc in an attempt to regain French control of the Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue on the island of Hispaniola, and curtail the measures of independence and abolition of slaves taken by the former slave Toussaint Louverture. It departed in December 1801 and, after initial success, ended in a French defeat at the Battle of Vertières and the departure of French troops in December 1803. The defeat forever ended Napoleon's dreams of a French empire in the West.

The Haitian Declaration of Independence was proclaimed on 1 January 1804 in the port city of Gonaïves by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, marking the end of 13-year long Haitian Revolution. The declaration marked Haiti becoming the first independent nation of Latin America and only the second in the Americas after the United States.

Afro-Haitians or Black Haitians are Haitians who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. They form the largest racial group in Haiti and together with other Afro-Caribbean groups, the largest racial group in the region.

White Haitians, are Haitians of predominant or full European. There were approximately 20,000 whites around the Haitian Revolution, mainly French, in Saint-Domingue. They were divided into two main groups: The Planters and Petit Blancs. The first Europeans to settle in Haiti were the Spanish. The Spanish enslaved the indigenous Haitians to work on sugar plantations and in gold mines. European diseases such as measles and smallpox killed all but a few thousand of the indigenous Haitians. Many other indigenous Haitians died from overwork and harsh treatment in the mines from slavery. Many Europeans who settled in Haiti were killed or fled during the Haitian Revolution.

Polish Haitians are Haitian people of Polish ancestry dating to the early 19th century; a few may be Poles of more recent native birth who have gained Haitian citizenship. Cazale, a small village in the hills about 30 kilometres (19 mi) away from Port-au-Prince, is considered the main center of population of the ethnic Polish community in Haiti, but there are other villages as well. Cazale has descendants of surviving members of Napoleon's Polish Legionnaires which were forced into combat by Napoleon but later joined the Haitian slaves during the Haitian Revolution. Some 400 to 500 of these Poles are believed to have settled in Haiti after the war. They were given special status as Noir and full citizenship under the Haitian constitution by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the first ruler of an independent Haiti.

The Indigenous Army, also known as the Army of Saint-Domingue was the name bestowed to the coalition of anti-slavery men and women who fought in the Haitian Revolution in Saint-Domingue. Encompassing both black slaves, maroons, and affranchis, the rebels were not officially titled the Armée indigène until January 1803, under the leadership of then-general Jean-Jacques Dessalines. Predated by insurrectionists such as François Mackandal, Vincent Ogé and Dutty Boukman, Toussaint Louverture, succeeded by Dessalines, led, organized, and consolidated the rebellion. The now full-fledged fighting force utilized its manpower advantage and strategic capacity to overwhelm French troops, ensuring the Haitian Revolution was the most successful of its kind.

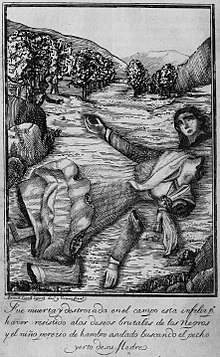

During the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804), Haitian women of all social positions participated in the revolt that successfully ousted French colonial power from the island. In spite of their various important roles in the Haitian Revolution, women revolutionaries have rarely been included within historical and literary narratives of the slave revolts. However, in recent years extensive academic research has been dedicated to their part in the revolution.

Genocide justification is the claim that a genocide is morally excusable/defensible, necessary, and/or sanctioned by law. Genocide justification differs from genocide denial, which is the attempt to reject the occurrence of genocide. Perpetrators often claim that genocide victims presented a serious threat, justifying their actions by stating it was legitimate self-defense of a nation or state. According to modern international criminal law, there can be no excuse for genocide. Genocide is often camouflaged as military activity against combatants, and the distinction between denial and justification is often blurred.

Saint-Domingue Creoles or simply Creoles, were the people who lived in the French colony of Saint-Domingue prior to the Haitian Revolution.

Moyse Hyacinthe L'Ouverture was a military leader in Saint-Domingue during the Haitian Revolution. Originally allied with Toussaint L'Ouverture, Moyse grew disillusioned with the minimal labor reform and land distribution for black former slaves under the L'Ouverture administration and lead a rebellion against Toussaint in 1801. Though executed, the insurrection he directed highlighted the failure of the Haitian Revolution in creating real revolutionary labor change and ignited the movement that drove L’Ouverture from office.