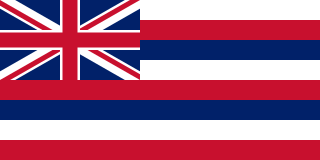

The Republic of Hawaii was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaiʻi between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had ended, and August 12, 1898, when it became annexed by the United States as an unincorporated and unorganized territory. In 1893, the Committee of Public Safety overthrew Queen Liliʻuokalani, the monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, after she rejected the 1887 Bayonet Constitution. The Committee of Public Safety intended for Hawaii to be annexed by the United States; however, President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat opposed to imperialism, refused. A new constitution was subsequently written while Hawaii was being prepared for annexation.

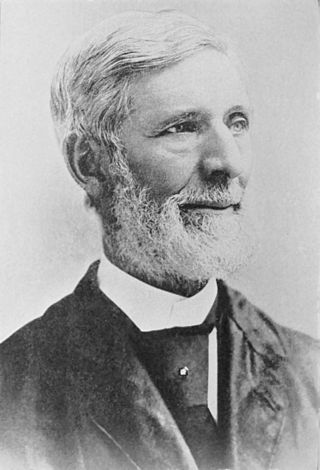

Sanford Ballard Dole was a Hawaii-born lawyer and jurist. He lived through the periods when Hawaii was a kingdom, provisional government, republic, and territory. Dole advocated the westernization of Hawaiian government and culture. After the overthrow of the monarchy, he served as the President of the Republic of Hawaii until his government secured Hawaii's annexation by the United States.

The Committee of Safety, formally the Citizen's Committee of Public Safety, was a 13-member group of the Annexation Club. The group was composed of mostly Hawaiian subjects of American descent and American citizens who were members of the Missionary Party, as well as some foreign residents in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi. The group planned and carried out the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi on January 17, 1893. The goal of this group was to achieve annexation of Hawaiʻi by the United States. The new independent Republic of Hawaiʻi government was thwarted in this goal by the administration of President Grover Cleveland, and it was not until 1898 that the United States Congress approved a joint resolution of annexation creating the U.S. Territory of Hawaiʻi.

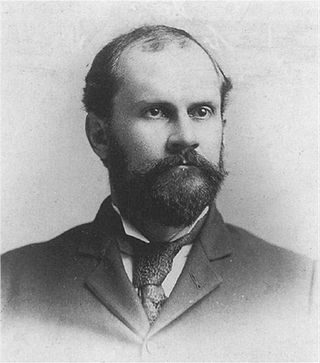

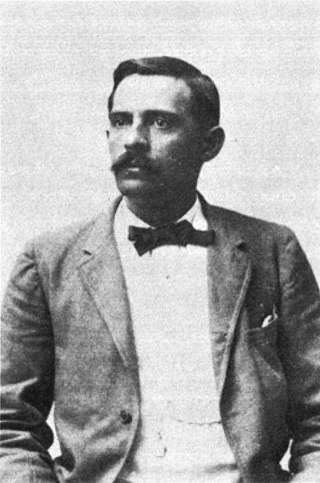

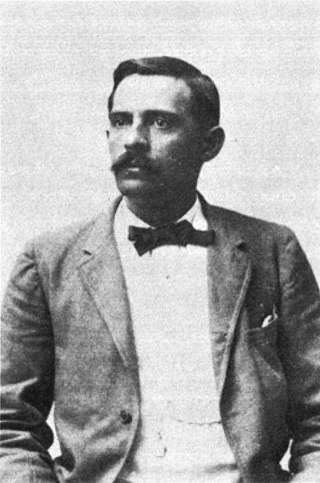

Lorrin Andrews Thurston was an American-Hawaiian lawyer, politician, and businessman. Thurston played a prominent role in the revolution that caused the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom that replaced Queen Liliʻuokalani with the Republic of Hawaii, guided by American ideas. He published the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, and owned other enterprises. From 1906 to 1916, he and his network lobbied with national politicians to create a national park to preserve the Hawaiian volcanoes.

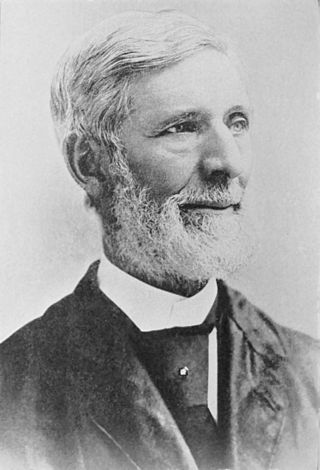

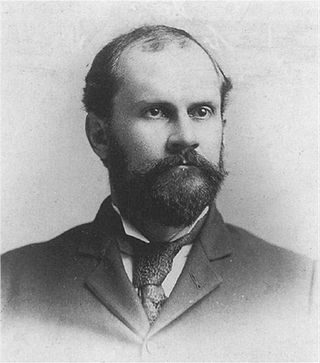

John Leavitt Stevens was the United States Minister to the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893 when he conspired to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani in association with the Committee of Safety, led by Lorrin A. Thurston and Sanford B. Dole – the first Americans attempting to overthrow a foreign government under the auspices of a United States government officer. Apart from his work as a politician and diplomat, he was also a journalist, author, minister and newspaper publisher. He founded the Republican Party in Maine and served as Maine State Senator.

The Provisional Government of Hawaii was proclaimed after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893, by the 13-member Committee of Safety under the leadership of its chairman Henry E. Cooper and former judge Sanford B. Dole as the designated President of Hawaii. It replaced the Kingdom of Hawaii after the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani as a provisional government until the Republic of Hawaii was established on July 4, 1894.

The Wilcox Rebellions were an armed rebellion in 1888, a revolt in 1889, and a counter-revolution in 1895, led by Robert William Wilcox against the promulgation of the Bayonet Constitution in 1888 and 1889, and against the overthrow of the monarchy in 1895. He was considered a royalist and dedicated to the monarchy of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Wilcox's revolts were part of the Hawaiian Rebellions.

The proposed 1893 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom would have been a replacement of the Constitution of 1887, primarily based on the Constitution of 1864 put forth by Queen Liliʻuokalani. While it never became anything more than a draft, the constitution had a profound impact on Hawaiʻi's history: it set off a chain of events that eventually resulted in the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was a coup d'état against Queen Liliʻuokalani, which took place on January 17, 1893, on the island of Oʻahu and led by the Committee of Safety, composed of seven foreign residents and six Hawaiian Kingdom subjects of American descent in Honolulu. The Committee prevailed upon American minister John L. Stevens to call in the U.S. Marines to protect the national interest of the United States of America. The insurgents established the Republic of Hawaii, but their ultimate goal was the annexation of the islands to the United States, which occurred in 1898.

Joseph Kahoʻoluhi Nāwahī, also known by his full Hawaiian name Iosepa Kahoʻoluhi Nāwahīokalaniʻōpuʻu, was a Native Hawaiian nationalist leader, legislator, lawyer, newspaper publisher, and painter. Through his long political service during the monarchy and the important roles he played in the resistance and opposition to its overthrow, Nāwahī is regarded as an influential Hawaiian patriot.

The Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands which existed from 1795 to 1893. It was established during the late 18th century when Hawaiian chief Kamehameha I, from the island of Hawaiʻi, conquered the islands of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, and Lānaʻi, and unified them under one government. In 1810, the Hawaiian Islands were fully unified when the islands of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau voluntarily joined the Hawaiian Kingdom. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom, the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

The Hawaiian rebellions and revolutions took place in Hawaii between 1887 and 1895. Until annexation in 1898, Hawaii was an independent sovereign state, recognized by the United States, United Kingdom, France and Germany with exchange of ambassadors. However, there were several challenges to the reigning governments of the Kingdom and Republic of Hawaii during the 8+1⁄2-year (1887–1895) period.

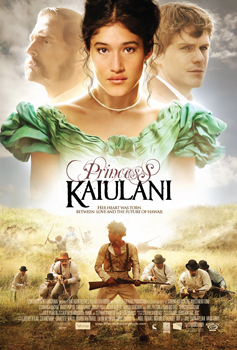

Princess Kaiulani is a 2009 British-American biographical drama film based on the life of Princess Kaʻiulani (1875–1899) of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi.

Luther Aholo was a politician who served many political posts in the Kingdom of Hawaii. He served multiple terms as a legislator from Maui and Minister of the Interior from 1886 to 1887. Considered one of the leading Hawaiian politicians of his generation, his skills as an orator were compared to those of the Ancient Greek statesman Solon.

John Francis Colburn was a businessman and politician of the Kingdom of Hawaii. He served as the last Minister of the Interior to Queen Liliuokalani. Even though he was part Hawaiian ancestry on his maternal side, Colburn was a key figure in the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and was a proponent of annexation to the United States. Colburn was the treasurer of the estate of Queen Kapiolani.

The 1892 Session of the Legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as the Longest Legislature, was a period from May 28, 1892, to January 14, 1893, in which the legislative assembly of the Hawaiian Kingdom met for its traditional bi-annual session. This unicameral body was composed of the upper House of Nobles and the lower House of Representatives. This would be the first session during the reign of Queen Liliʻuokalani and the last meeting of the legislative assembly during the Hawaiian monarchy. Three days after the prorogation of the assembly, many of the political tension developed during the legislative debates and the queen's attempt to promulgate a new constitution while her legislators were not in session led to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom on January 17, 1893.

David William Pua, also known as D. W. Pua, was a politician during the Kingdom of Hawaii. He served as a legislator during the last years of the Legislature of the Kingdom of Hawaii and became a member of the Hui Aloha ʻĀina, founded after the overthrow of the monarchy to protest attempts of annexation to the United States.

Jonathan Austin was a veteran of the American Civil War, president of Paukaa Sugar Company, and Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Kingdom of Hawaii during the reign of Kalākaua.

The Hui Kālaiʻāina was a political group founded in 1888 to oppose the 1887 Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, often known as the Bayonet Constitution, and to promote Native Hawaiian leadership in the government. It and the two organizations of Hui Aloha ʻĀina were active in the opposition to the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the annexation of Hawaii to the United States from 1893 to 1898.

Charles F. Creighton (1862–1907) was a member of Queen Liliʻuokalani's Cabinet Ministers as Attorney General of the Kingdom of Hawaii for the period November 1–8, 1892. Following the Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, he was arrested for his involvement in the 1895 Wilcox rebellion attempt to restore the monarchy. He accepted temporary exile to the United States to avoid a lengthy incarceration. His father Robert James Creighton had served as Kalākaua's Minister of Foreign Affairs.