Related Research Articles

Orval Eugene Faubus was an American politician who served as the 36th Governor of Arkansas from 1955 to 1967, as a member of the Democratic Party.

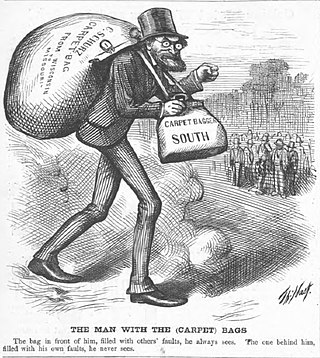

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the local populace for their own financial, political, and/or social gain. The term broadly included both individuals who sought to promote Republican politics and individuals who saw business and political opportunities because of the chaotic state of the local economies following the war. In practice, the term carpetbagger was often applied to any Northerners who were present in the South during the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877). The term is closely associated with "scalawag", a similarly pejorative word used to describe native white Southerners who supported the Republican Party-led Reconstruction.

Southern Democrats are affiliates of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Most of them voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by holding the longest filibuster in American Senate history while Democrats in non-Southern states supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964. After 1994 the Republicans typically won most elections in the South.

The Red Shirts or Redshirts of the Southern United States were white supremacist paramilitary terrorist groups that were active in the late 19th century in the last years of, and after the end of, the Reconstruction era of the United States. Red Shirt groups originated in Mississippi in 1875, when anti-Reconstruction private terror units adopted red shirts to make themselves more visible and threatening to Southern Republicans, both whites and freedmen. Similar groups in the Carolinas also adopted red shirts.

The South Carolina civil disturbances of 1876 were a series of race riots and civil unrest related to the Democratic Party's political campaign to take back control from Republicans of the state legislature and governor's office through their paramilitary Red Shirts division. Part of their plan was to disrupt Republican political activity and suppress black voting, particularly in counties where populations of whites and blacks were close to equal. Former Confederate general Martin W. Gary's "Plan of the Campaign of 1876" gives the details of planned actions to accomplish this.

The Democratic Party of Arkansas is the affiliate of the Democratic Party in the state of Arkansas. The current party chair is Grant Tennille.

The North Carolina Republican Party (NCGOP) is the affiliate of the Republican Party in North Carolina. Michael Whatley has been the chair since 2019. It is currently the state's favored party, controlling half of North Carolina's U.S. House seats, both U.S. Senate seats, and a 3/5 supermajority control of both chambers of the state legislature, as well as a majority on the state supreme court.

Lewis Porter Featherstone was an American planter and farm activist who served for one year as a Labor Party U.S. Representative from Arkansas from 1890 to 1891.

William Henderson Cate was an American politician, lawyer and judge. In 1889 and 1890, he served part of one term as a U.S. Representative from Arkansas. He was removed from his seat following an investigation of election fraud before regaining the seat in the subsequent election, serving an additional term from 1891 to 1893.

The Election Massacre of 1874, or Coup of 1874, took place on election day, November 3, 1874, near Eufaula, Alabama in Barbour County. Freedmen comprised a majority of the population and had been electing Republican candidates to office. Members of an Alabama chapter of the White League, a paramilitary group supporting the Democratic Party's drive to regain political power in the county and state, used firearms to ambush black Republicans at the polls.

John Middleton Clayton was an American politician who served as a Republican member of the Arkansas House of Representatives for Jefferson County from 1871 to 1873 and the Arkansas State Senate for Jefferson County. In 1888, he ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives but lost to Clifton R. Breckinridge. Clayton challenged the results and was assassinated in 1889 during the challenge to the election. He was declared the winner of the election posthumously. The identity of his assassin remains unknown.

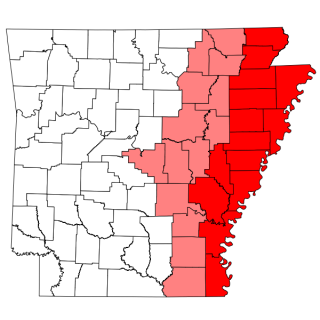

The Arkansas Delta is one of the six natural regions of the state of Arkansas. Willard B. Gatewood Jr., author of The Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox, says that rich cotton lands of the Arkansas Delta make that area "The Deepest of the Deep South."

The State government of Arkansas is divided into three branches: executive, legislative and judicial. These consist of the state governor's office, a bicameral state legislature known as the Arkansas General Assembly, and a state court system. The Arkansas Constitution delineates the structure and function of the state government. Since 1963, Arkansas has had four seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Like all other states, it has two seats in the U.S. Senate.

James Ray Caldwell, known as Jim R. Caldwell, is a retired Church of Christ minister in Tulsa, Oklahoma, who was a Republican member of the Arkansas State Senate from 1969 to 1978, the first member of his party to sit in the legislative upper chamber in the 20th century. His first two years as a senator corresponded with the second two-year term of Winthrop Rockefeller, the first Republican governor of Arkansas since Reconstruction. Caldwell was closely allied with Rockefeller during the 1969-1970 legislative sessions.

The 1937 Arkansas special senatorial election was held on October 19, 1937, following the death of longtime Democratic senator Joe T. Robinson. Robinson was a powerful senator, staunch Democrat, and strong supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was instrumental in passing many New Deal programs through the Senate. Arkansas was essentially a one-party state during the Solid South period; the Democratic Party controlled all aspects of state and local office. Recently elected Democratic Governor of Arkansas Carl E. Bailey initially considered appointing himself to finish Robinson's term, but later acceded to a nomination process by the Democratic Central Committee, avoiding a public primary but breaking a campaign process. Avoiding the primary so angered the public and establishment Democrats, leading them to coalesce behind longtime Democrat John E. Miller as an independent, forcing a general election.

The 1932 Arkansas gubernatorial election was held on November 8, 1932, to elect the Governor of Arkansas, concurrently with the election to Arkansas's Class III U.S. Senate seat, as well as other elections to the United States Senate in other states and elections to the United States House of Representatives and various state and local elections.

The 1944 United States presidential election in Mississippi took place on November 7, 1944, as part of the 1944 United States presidential election. Mississippi voters chose nine representatives, or electors, to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president.

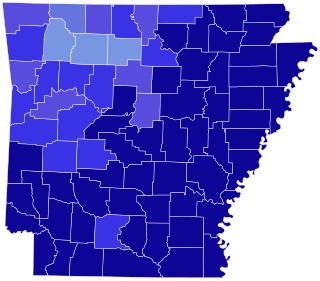

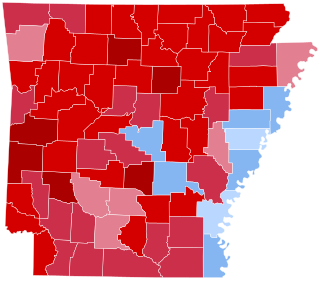

The 2020 United States presidential election in Arkansas took place on Tuesday, November 3, 2020, as part of the 2020 United States presidential election in which all 50 states plus the District of Columbia participated. Arkansas voters chose six electors to represent them in the Electoral College via a popular vote pitting incumbent Republican President Donald Trump and his running mate, incumbent Vice President Mike Pence, against Democratic challenger and former Vice President Joe Biden and his running mate, United States Senator Kamala Harris of California. Also on the ballot were the nominees for the Libertarian, Green, Constitution, American Solidarity, Life and Liberty, and Socialism and Liberation parties and Independent candidates. Write-in candidates are not allowed to participate in presidential elections.

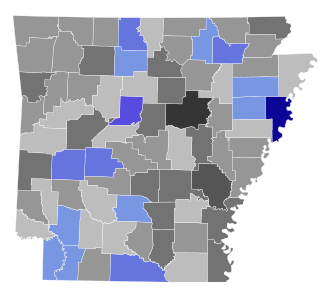

The 1888 Arkansas gubernatorial election was held on September 3, 1888.