Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

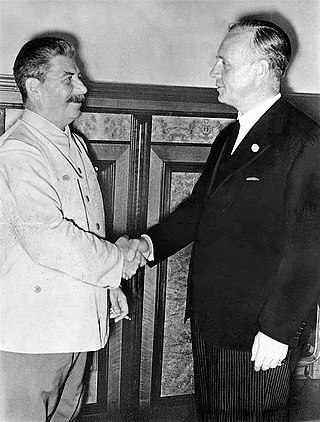

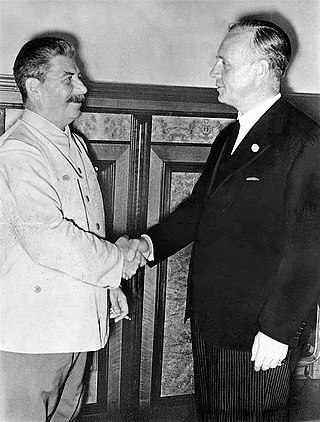

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that partitioned Eastern Europe between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and was officially known as the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Unofficially, it has also been referred to as the Hitler–Stalin Pact, Nazi–Soviet Pact or Nazi–Soviet Alliance.

The Polish Corridor, also known as the Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia, which provided the Second Republic of Poland (1920–1939) with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East Prussia. At its narrowest point, the Polish territory was just 30 km wide. The Free City of Danzig, situated to the east of the corridor, was a semi-independent German speaking city-state forming part of neither Germany nor Poland, though united with the latter through an imposed union covering customs, mail, foreign policy, railways as well as defence.

In Nazi German terminology, Volksdeutsche were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of volksdeutsch, with Volksdeutsche denoting a singular female, and Volksdeutsche(r), a singular male. The words Volk and völkisch conveyed the meanings of "folk".

The Munich Agreement was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. The agreement provided for the German annexation of land on the border between Czechoslovakia and Germany called the Sudetenland, where more than three million people, mainly ethnic Germans, lived. The pact is also known in some areas as the Munich Betrayal, because of a previous 1924 alliance agreement and a 1925 military pact between France and the Czechoslovak Republic.

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, War of Poland of 1939, and Polish Defencive War of 1939, was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak Republic, and the Soviet Union; which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week after the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union, and one day after the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union had approved the pact. The Soviets invaded Poland on 17 September. The campaign ended on 6 October with Germany and the Soviet Union dividing and annexing the whole of Poland under the terms of the German–Soviet Frontier Treaty. The invasion is also known in Poland as the September campaign or 1939 defensive war and known in Germany as the Poland campaign.

Klaus Hildebrand is a German liberal-conservative historian whose area of expertise is 19th–20th-century German political and military history.

Eduard Willy Kurt Herbert von Dirksen was a German diplomat who was the last German ambassador to Britain before World War II.

The Gaue were the main administrative divisions of Nazi Germany from 1934 to 1945.

The presence of German-speaking populations in Central and Eastern Europe is rooted in centuries of history, with the settling in northeastern Europe of Germanic peoples predating even the founding of the Roman Empire. The presence of independent German states in the region, and later the German Empire as well as other multi-ethnic countries with German-speaking minorities, such as Hungary, Poland, Imperial Russia, etc., demonstrates the extent and duration of German-speaking settlements.

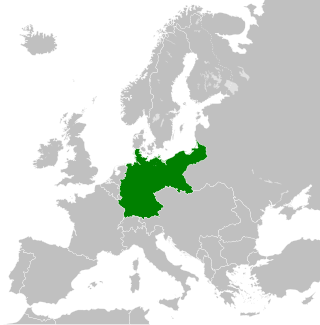

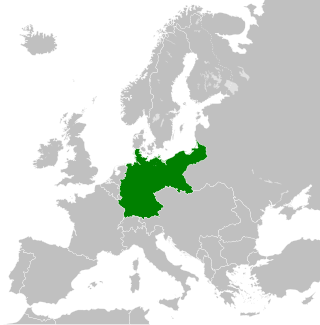

The territorial evolution of Germany in this article include all changes in the modern territory of Germany from its unification making it a country on 1 January 1871 to the present although the history of "Germany" as a territorial polity concept and the history of the ethnic Germans are much longer and much more complex. Modern Germany was formed when the Kingdom of Prussia unified most of the German states, with the typical exception of multi-ethnic Austria where was ruled by German-speaking royal family of Habsburg and had a significant German-speaking land, into the German Empire. After the First World War, on 10 January 1920, Germany lost about 10% of its territory to its neighbours, and the Weimar Republic was formed two days before this war was over. This republic included territories to the east of today's German borders.

The Anschluss, also known as the Anschluß Österreichs, was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 12 March 1938.

History of Pomerania between 1933 and 1945 covers the period of one decade of the long history of Pomerania, lasting from the Adolf Hitler's rise to power until the end of World War II in Europe. In 1933, the German Province of Pomerania like all of Germany came under control of the Nazi regime. During the following years, the Nazis led by Gauleiter Franz Schwede-Coburg manifested their power through the process known as Gleichschaltung and repressed their opponents. Meanwhile, the Pomeranian Voivodeship was part of the Second Polish Republic, led by Józef Piłsudski. With respect to Polish Pomerania, Nazi diplomacy – as part of their initial attempts to subordinate Poland into Anti-Comintern Pact – aimed at incorporation of the Free City of Danzig into the Third Reich and an extra-territorial transit route through Polish territory, which was rejected by the Polish government, that feared economic blackmail by Nazi Germany, and reduction to puppet status.

The Military Administration in Poland refers to the military occupation authorities established in the brief period during, and in the immediate aftermath of, the German invasion of Poland, in which the occupied Polish territories were administered by the German military (Wehrmacht) as opposed to the later civil administration and the General Government.

The States of the Weimar Republic were the first-level administrative divisions and constituent states of the German Reich during the Weimar Republic era. The states were established in 1918 following the German Revolution upon the conclusion of World War I, and based on the 22 constituent states of the German Empire that abolished their local monarchies. The new states continued as republics alongside the three pre-existing republican city-states within the new Weimar Republic, adopting the titles Freistaat or Volksstaat.

Hans-Adolf Helmuth Ludwig Erdmann Waldemar von Moltke was a German landowner in Silesia who became a diplomat. He served as ambassador in Poland during the Weimar Republic. After the German invasion of Poland, he became Adolf Hitler's ambassador in Spain during the Second World War.

The Danzig crisis was a 1939 crisis that led to World War II breaking out in Europe.

The following events occurred in August 1939:

Johannes Bernhard Graf von Welczeck was a Nazi German diplomat who served as the last German ambassador to France before World War II.