François Roland Truffaut was a French filmmaker, actor, and critic. He is widely regarded as one of the founders of the French New Wave. With a career of more than 25 years, he is an icon of the French film industry.

French cinema consists of the film industry and its film productions, whether made within the nation of France or by French film production companies abroad. It is the oldest and largest precursor of national cinemas in Europe; with primary influence also on the creation of national cinemas in Asia.

Jean-Luc Godard was a French and Swiss film director, screenwriter, and film critic. He rose to prominence as a pioneer of the French New Wave film movement of the 1960s, alongside such filmmakers as François Truffaut, Agnès Varda, Éric Rohmer and Jacques Demy. He was arguably the most influential French filmmaker of the post-war era. According to AllMovie, his work "revolutionized the motion picture form" through its experimentation with narrative, continuity, sound, and camerawork. His most acclaimed films include Breathless (1960), Vivre sa vie (1962), Contempt (1963), Band of Outsiders (1964), Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le Fou (1965), Masculin Féminin (1966), Weekend (1967) and Goodbye to Language (2014).

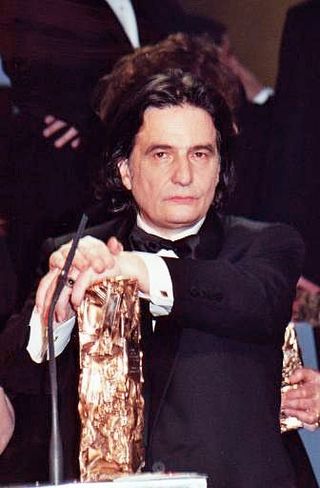

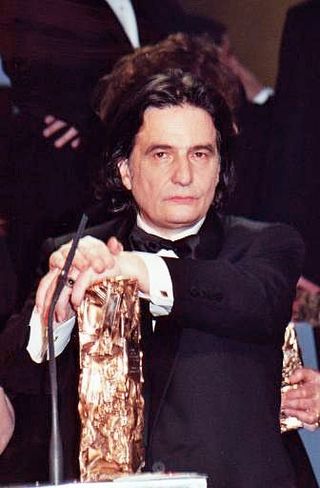

Jean-Louis Xavier Trintignant was a French actor. He made his theatrical debut in 1951, and went on to be regarded as one of the best French dramatic actors of the post-war era. He starred in many classic films of European cinema, and worked with many prominent auteur directors, including Roger Vadim, Costa-Gavras, Claude Lelouch, Claude Chabrol, Bernardo Bertolucci, Éric Rohmer, François Truffaut, Krzysztof Kieślowski, and Michael Haneke.

Jean-Pierre Léaud, ComM is a French actor best known for his portrayal of Antoine Doinel in a series of films by François Truffaut, beginning with The 400 Blows (1959). Léaud is a significant figure of the French New Wave, having also worked with Jean-Luc Godard, Agnès Varda, and Jacques Rivette, as well as other notable directors such as Jean Cocteau, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci, Catherine Breillat, Jerzy Skolimowski, and Aki Kaurismäki.

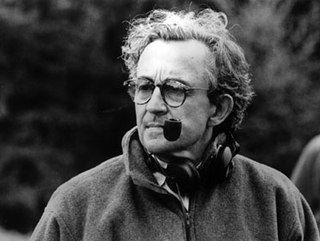

Louis Marie Malle was a French film director, screenwriter, and producer who worked in both French cinema and Hollywood. Described as "eclectic" and "a filmmaker difficult to pin down", Malle made documentaries, romances, period dramas, and thrillers. He often depicted provocative or controversial subject matter.

Henri Langlois was a French film archivist and cinephile. A pioneer of film preservation, Langlois was an influential figure in the history of cinema. His film screenings in Paris in the 1950s are often credited with providing the ideas that led to the development of the auteur theory.

Jacques Rivette was a French film director and film critic most commonly associated with the French New Wave and the film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. He made twenty-nine films, including L'Amour fou (1969), Out 1 (1971), Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), and La Belle Noiseuse (1991). His work is noted for its improvisation, loose narratives, and lengthy running times.

Jeanne Moreau was a French actress, singer, screenwriter, director, and socialite. She made her theatrical debut in 1947, and established herself as one of the leading actresses of the Comédie-Française. Moreau began playing small roles in films in 1949, later achieving prominence with starring roles in Louis Malle's Elevator to the Gallows (1958), Michelangelo Antonioni's La Notte (1961), and François Truffaut's Jules et Jim (1962). Most prolific during the 1960s, Moreau continued to appear in films into her 80s. Orson Welles called her "the greatest actress in the world".

The Cinémathèque française, founded in 1936, is a French non-profit film organization that holds one of the largest archives of film documents and film-related objects in the world. Based in Paris's 12th arrondissement, the archive offers daily screenings of worldwide films.

Daniel Boulanger was a French novelist, playwright, poet and screenwriter. He has also played secondary roles in films and was a member of the Académie Goncourt from 1983 until his death. He was born in Compiègne, Oise.

Charles Denner was a French actor born to a Jewish family in Tarnów, Poland. During his 30-year career he worked with some of France's greatest directors of the time, including Louis Malle, Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Costa-Gavras, Claude Lelouch and François Truffaut, who gave him two of his most memorable roles, as Fergus in The Bride Wore Black (1968) and as Bertrand Morane in The Man Who Loved Women (1977).

Claude Miller was a French film director, producer and screenwriter.

The French Syndicate of Cinema Critics has, each year since 1946, awarded a prize, the Prix Méliès, to the best French film of the preceding year. More awards have been added over time: the Prix Léon Moussinac for the best foreign film, added in 1967; the Prix Novaïs-Texeira for the best short film, added in 1999; prizes for the best first French and best first foreign films, added in 2001 and 2014, respectively; etc.

Alexandra Stewart is a Canadian actress.

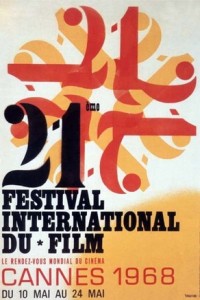

The 26th Cannes Film Festival was held from 10 to 25 May 1973. The Grand Prix du Festival International du Film went to Scarecrow by Jerry Schatzberg and The Hireling by Alan Bridges. At this festival two new non-competitive sections were added: 'Étude et documents' and 'Perspectives du Cinéma Français'.

Letter in Motion to Gilles Jacob and Thierry Frémaux is a 2014 short film directed by Jean-Luc Godard.

Pierre-André Boutang was a French documentary filmmaker, producer and director. He was one of the leaders of the Franco-German channel Arte as well as of La Sept previously.