The 1972 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XX Olympiad and commonly known as Munich 1972, was an international multi-sport event held in Munich, West Germany, from 26 August to 11 September 1972.

The 1968 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XIX Olympiad and commonly known as Mexico 1968, were an international multi-sport event held from 12 to 27 October 1968 in Mexico City, Mexico. These were the first Olympic Games to be staged in Latin America and the first to be staged in a Spanish-speaking country. They were also the first Games to use an all-weather (smooth) track for track and field events instead of the traditional cinder track, as well as the first example of the Olympics exclusively using electronic timekeeping equipment.

Avery Brundage was an American sports administrator who served as the fifth president of the International Olympic Committee from 1952 to 1972. The only American and only non-European to attain that position, Brundage is remembered as a zealous advocate of amateurism and for his involvement with the 1936 and 1972 Summer Olympics, both held in Germany.

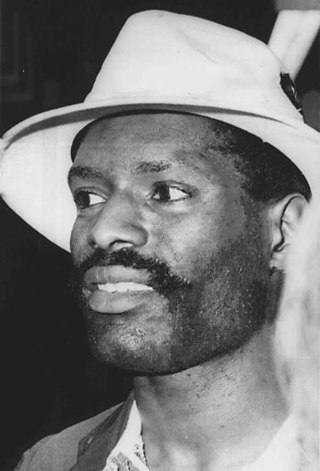

Tommie C. Smith is an American former track and field athlete and former wide receiver in the American Football League. At the 1968 Summer Olympics, Smith, aged 24, won the 200-meter sprint finals and gold medal in 19.83 seconds – the first time the 20-second barrier was broken officially. His Black Power salute with John Carlos atop the medal podium to protest racism and injustice against African Americans in the United States caused controversy, as it was seen as politicizing the Olympic Games. It remains a symbolic moment in the history of the Black Power movement.

Lee Edward Evans was an American sprinter. He won two gold medals in the 1968 Summer Olympics, setting world records in the 400 meters and the 4 × 400 meters relay, both of which stood for 20 and 24 years respectively. Evans co-founded the Olympic Project for Human Rights and was part of the athlete's boycott and the Black Power movement.

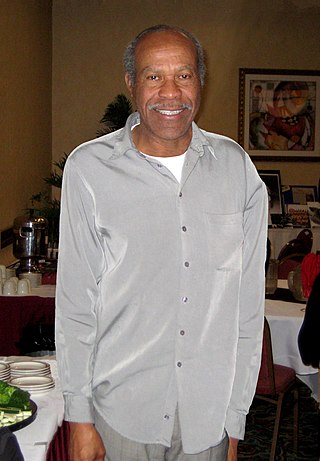

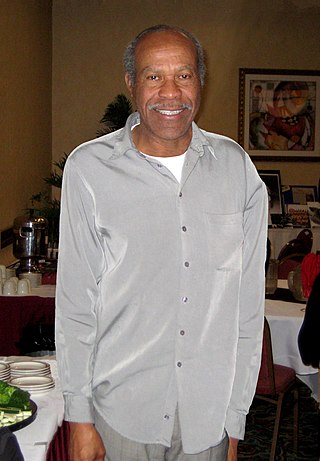

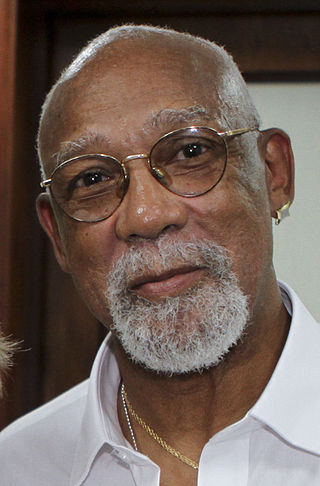

Vincent "Vince" Edward Matthews is an American former sprinter, winner of two Olympic gold medals, at the 1968 Summer Olympics and 1972 Summer Olympics.

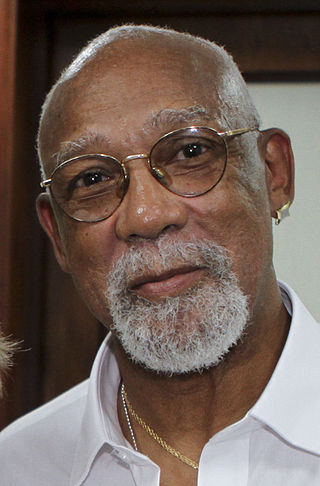

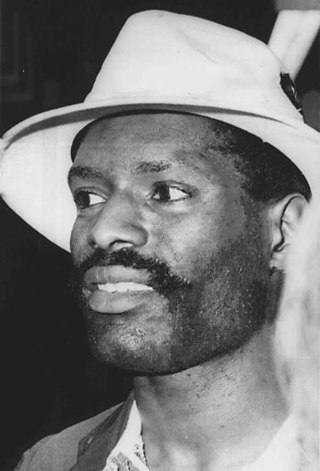

John Wesley Carlos is an American former track and field athlete and professional American football player. He was the bronze-medal winner in the 200 meters at the 1968 Summer Olympics, where he displayed the Black Power salute on the podium with Tommie Smith. He went on to tie the world record in the 100-yard dash and beat the 200 meters world record. After his track career, he enjoyed a brief stint in the Canadian Football League but retired due to injury.

During their medal ceremony in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City on October 16, 1968, two African-American athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, each raised a black-gloved fist during the playing of the US national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner". While on the podium, Smith and Carlos, who had won gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200-meter running event of the 1968 Summer Olympics, turned to face the US flag and then kept their hands raised until the anthem had finished. In addition, Smith, Carlos, and Australian silver medalist Peter Norman all wore human-rights badges on their jackets.

Wayne Curtis Collett was an African-American Olympic sprinter. Collett won a silver medal in the 400 m at the 1972 Summer Olympics. During the medal ceremony Collett and winner Vincent Matthews talked to each other, shuffled their feet, stroked their chins and fidgeted while the US national anthem played, leading many to believe it was a Black Power protest like the 1968 Olympics Black Power salute by Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

John Walton Smith is a former American athlete, who competed in the sprints events during his career. He is best known for winning the 400 m event at the 1971 Pan American Games. He remains the world record holder for the 440 yard dash at 44.5 seconds. He set the record while winning the USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships on June 26, 1971 while running for the Southern California Striders. The record has stood since then due to metrification in the sport. Contemporary athletes rarely run or are timed officially for the extra 2.34 meters to equal 440 yards.

The United States Olympic trials for the sport of track and field is the quadrennial meet to select the United States representatives at the Olympic Games. Since 1992, the meet has also served as the year's USA Outdoor Track and Field Championships. Because of the depth of competition in some events, this has been considered by many to be the best track meet in the world. The event is regularly shown on domestic U.S. Television and covered by a thousand members of the worldwide media. As with all Olympic sports, the meet is conducted by the national governing body for the sport, currently USA Track & Field (USATF), which was previously named The Athletics Congress (TAC) until 1992. Previous to the formation of TAC in 1979, the national governing body for most sports was the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU).

The men's 400 metres was an event at the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. The competition was held on 3, 4 and 7 September. Sixty-four athletes from 49 nations competed. The maximum number of athletes per nation had been set at 3 since the 1930 Olympic Congress. The event was won by Vince Matthews of the United States, the nation's fifth consecutive and 12th overall victory in the event. The Americans' hopes to repeat their podium sweep of four years earlier were dashed by injury in the final. Bronze medalist Julius Sang became the first black African to win a sprint Olympic medal, earning Kenya's first medal in the event.

The men's 4 × 400 metres relay was the longer of the two men's relays on the Athletics at the 1972 Summer Olympics program in Munich. It was held on 9 September and 10 September 1972.

Maurice Peoples is an American former sprinter.

Tracy Evans Smith is a former American distance runner. He was a member of the 1968 U.S. Olympic Track and Field Team, competing in the 10,000 meters. He was ranked multiple times by Track & Field News as the No. 1 U.S. 5,000- and 10,000-meter runner in the mid- to late ‘60s, and was a six-time AAU National Champion from 1966 to 1973, winning outdoors in the 3-mile, 6-mile and 10,000 meters, and three times in the indoor 3-mile. He was a three-time world record holder in the indoor 3-mile.

Michael Arthur Norman Jr. is an American sprinter. He holds the world best time in the indoor 400 meters at 44.52 seconds. Outdoors, his 43.45, set at the 2019 Mt. SAC Relays is tied as the #4 on the all time list. In 2016, he became the world junior champion in both the 200 meters and 4×100 meter relay. In 2022, he became the world champion in both the 400 meters and 4x400 meter relay.

Courtney Frerichs is an American middle-distance runner and steeplechase specialist from Nixa, Missouri, She is a three-time silver medalist in the 3000 meters steeplechase capturing silver at the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, the 2017 World Championships in London and at the 2018 World (Continental) Cup in Ostrava. In 2021, she became the first American woman to run under nine-minutes in a women’s 3000-meters steeplechase event with a time of 8:57.77; establishing an American and Area record. She is a two-time Olympian making the US team in 2016 and 2020. In both of her Olympic Trials she finished second to US National Champion, Emma Coburn.

Protests during the playing of the United States national anthem have had many causes, including civil rights, anti-conscription, anti-war, anti-nationalism, and religious reservations. Such protests have occurred since at least the 1890s, well before "The Star-Spangled Banner" was adopted and resolved by Congress as the official national anthem in 1916 and 1931, respectively. Earlier protests typically took place during the performance of various unofficial national anthems, including "My Country, 'Tis of Thee" and "Hail, Columbia". These demonstrations may include refusal to stand or face the American flag during the playing of the Anthem. Some of the protestors object to honoring the slaveowner and author of the lyrics, Francis Scott Key.

William "Woody" Kincaid is an American long-distance runner. He won the gold medal in the 5000 meters at the 2022 NACAC Championships. Kincaid is the North American indoor record holder for that event.