The Fujita scale, or Fujita–Pearson scale, is a scale for rating tornado intensity, based primarily on the damage tornadoes inflict on human-built structures and vegetation. The official Fujita scale category is determined by meteorologists and engineers after a ground or aerial damage survey, or both; and depending on the circumstances, ground-swirl patterns, weather radar data, witness testimonies, media reports and damage imagery, as well as photogrammetry or videogrammetry if motion picture recording is available. The Fujita scale was replaced with the Enhanced Fujita scale (EF-Scale) in the United States in February 2007. In April 2013, Canada adopted the EF-Scale over the Fujita scale along with 31 "Specific Damage Indicators" used by Environment Canada (EC) in their ratings.

The 1974 Super Outbreak was the second-largest tornado outbreak on record for a single 24-hour period, just behind the 2011 Super Outbreak. It was also the most violent tornado outbreak ever recorded, with 30 F4/F5 tornadoes confirmed. From April 3–4, 1974, there were 148 tornadoes confirmed in 13 U.S. states and the Canadian province of Ontario. In the United States, tornadoes struck Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, and New York. The outbreak caused roughly $843 million USD in damage, with more than $600 million occurring in the United States. The outbreak extensively damaged approximately 900 sq mi (2,331 km2) along a total combined path length of 2,600 mi (4,184 km). At one point, as many as 15 separate tornadoes were occurring simultaneously.

On April 10–12, 1965, a historic severe weather event affected the Midwestern and Southeastern United States. The tornado outbreak produced 55 confirmed tornadoes in one day and 16 hours. The worst part of the outbreak occurred during the afternoon hours of April 11 into the overnight hours going into April 12. The second-largest tornado outbreak on record at the time, this deadly series of tornadoes, which became known as the 1965 Palm Sunday tornado outbreak, inflicted a swath of destruction from Cedar County, Iowa, to Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and a swath 450 miles long (724 km) from Kent County, Michigan, to Montgomery County, Indiana. The main part of the outbreak lasted 16 hours and 35 minutes and is among the most intense outbreaks, in terms of tornado strength, ever recorded, including at least four "double/twin funnel" tornadoes. In all, the outbreak killed 266 people, injured 3,662 others, and caused $1.217 billion in damage. In 2023, tornado expert Thomas P. Grazulis created the outbreak intensity score (OIS) as a way to rank various tornado outbreaks. The 1965 Palm Sunday tornado outbreak received an OIS of 238, making it the third worst tornado outbreak in recorded history.

This article lists various tornado records. The most "extreme" tornado in recorded history was the Tri-State tornado, which spread through parts of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana on March 18, 1925. It is considered an F5 on the Fujita Scale, holds records for longest path length at 219 miles (352 km), longest duration at about 3+1⁄2 hours, and it held the fastest forward speed for a significant tornado at 73 mph (117 km/h) anywhere on Earth until 2021. In addition, it is the deadliest single tornado in United States history with 695 fatalities. It was also the third most costly tornado in history at the time, when costs are normalized for wealth and inflation, it still ranks third today.

The 1985 United States–Canada tornado outbreak, referred to as the Barrie tornado outbreak in Canada, was a major tornado outbreak that occurred in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Ontario, on May 31, 1985. In all 44 tornadoes were counted including 14 in Ontario, Canada. It is the largest and most intense tornado outbreak ever to hit this region, and the worst tornado outbreak in Pennsylvania history in terms of deaths and destruction.

The Enhanced Fujita scale rates tornado intensity based on the severity of the damage they cause. It is used in some countries, including the United States, Canada, France, and Japan. The EF scale is also unofficially used in other countries including China.

A violent severe weather outbreak struck the Southeast on April 4–5, 1977. A total of 22 tornadoes touched down with the strongest ones occurring in Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. The strongest was a catastrophic F5 tornado that struck the northern Birmingham, Alabama, suburbs during the afternoon of Monday, April 4. In addition to this tornado, several other tornadoes were reported from the same system in the Midwest, Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi and North Carolina. One tornado in Floyd County, Georgia, killed one person, and another fatality was reported east of Birmingham in St. Clair County. In the end, the entire outbreak directly caused 24 deaths and 158 injuries. The storm system also caused the crash of Southern Airways Flight 242, which killed 72 and injured 22.

On April 21–24, 1968, a deadly tornado outbreak struck portions of the Midwestern United States, primarily along the Ohio River Valley. The worst tornado was an F5 that struck portions of Southeastern Ohio from Wheelersburg to Gallipolis, just north of the Ohio–Kentucky state line, killing seven people and injuring at least 93. Another long-tracked violent tornado killed six people, injured 364 others, and produced possible F5 damage as it tracked along the Ohio River. At least one other violent tornado caused an additional fatality and 33 injuries in Ohio. In the end, at least 26 tornadoes touched down, leaving 14 dead, including five in Kentucky and nine in Ohio.

On March 21–22, 1952, a severe tornado outbreak generated eight violent tornadoes across the Southern United States, causing 209 fatalities—50 of which occurred in a single tornado in Arkansas. In addition, this tornado outbreak is the deadliest on record to ever affect the state of Tennessee, with 66 of the fatalities associated with this outbreak occurring in the state; this surpasses the 60 fatalities from a tornado outbreak in 1909, and in terms of fatalities is well ahead of both the 1974 Super Outbreak and the Super Tuesday tornado outbreak, each of which generated 45 and 31 fatalities, respectively. The severe weather event also resulted in the fourth-largest number of tornado fatalities within a 24-hour period since 1950. To date this was considered the most destructive tornado outbreak in Arkansas on record.

On February 21–22, 1971, a devastating tornado outbreak, colloquially known as the Mississippi Delta outbreak, struck portions of the Lower Mississippi and Ohio River valleys in the Southern and Midwestern United States. The outbreak generated strong tornadoes from Texas to Ohio and North Carolina. The two-day severe weather episode produced at least 19 tornadoes, and probably several more, mostly brief events in rural areas; killed 123 people across three states; and wrecked entire communities in the state of Mississippi. The strongest tornado of the outbreak was an F5 that developed in Louisiana and crossed into Mississippi, killing 48 people, while the deadliest was an F4 that tracked across Mississippi and entered Tennessee, causing 58 fatalities in the former state. The former tornado remains the only F5 on record in Louisiana, while the latter is the deadliest on record in Mississippi since 1950. A deadly F4 also affected other parts of Mississippi, causing 13 more deaths. Other deadly tornadoes included a pair of F3s—one each in Mississippi and North Carolina, respectively—that collectively killed five people.

On June 3–4, 1958, a destructive tornado outbreak affected the Upper Midwestern United States. It was the deadliest tornado outbreak in the U.S. state of Wisconsin since records began in 1950. The outbreak, which initiated in Central Minnesota, killed at least 28 people, all of whom perished in Northwestern Wisconsin. The outbreak generated a long-lived tornado family that produced four intense tornadoes across the Eau Claire–Chippewa Falls metropolitan area, primarily along and near the Chippewa and Eau Claire rivers. The deadliest tornado of the outbreak was a destructive F5 that killed 21 people and injured 110 others in and near Colfax, Wisconsin.

On March 21–22, 1932, a deadly tornado outbreak struck the Midwestern and Southern United States. At least 38 tornadoes—including 27 deadly tornadoes and several long-lived tornado families—struck the Deep South, killing more than 330 people and injuring 2,141. Tornadoes affected areas from Mississippi north to Illinois and east to South Carolina, but Alabama was hardest hit, with 268 fatalities; the outbreak is considered to be the deadliest ever in Alabama, and among the worst ever in the United States, trailing only the Tri-State tornado outbreak in 1925, with 751 fatalities, and the Tupelo–Gainesville outbreak in 1936, with 454 fatalities. The 1932 outbreak is believed to have produced 10 violent tornadoes, eight of which occurred in Alabama alone.

Tornadoes are more common in the United States than in any other country or state. The United States receives more than 1,200 tornadoes annually—four times the amount seen in Europe. Violent tornadoes—those rated EF4 or EF5 on the Enhanced Fujita Scale—occur more often in the United States than in any other country.

This page documents the tornadoes and tornado outbreaks of 1990, primarily in the United States. Most tornadoes form in the U.S., although some events may take place internationally. Tornado statistics for older years like this often appear significantly lower than modern years due to fewer reports or confirmed tornadoes, however by the 1990s tornado statistics were coming closer to the numbers we see today.

On December 18–20, 1957, a significant tornado outbreak sequence affected the southern Midwest and the South of the contiguous United States. The outbreak sequence began on the afternoon of December 18, when a low-pressure area approached the southern portions of Missouri and Illinois. Supercells developed and proceeded eastward at horizontal speeds of 40 to 45 miles per hour, yielding what was considered the most severe tornado outbreak in Illinois on record so late in the calendar year. Total losses in the state were estimated to fall within the range of $8–$10 million.

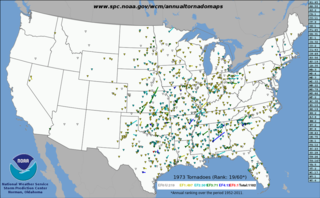

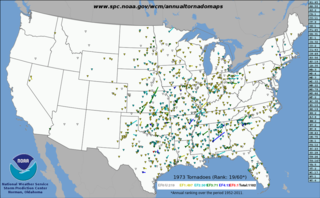

This page documents the tornadoes and tornado outbreaks of 1974, primarily in the United States. Most tornadoes form in the U.S., although some events may take place internationally. Tornado statistics for older years like this often appear significantly lower than modern years due to fewer reports or confirmed tornadoes.

This page documents notable tornadoes and tornado outbreaks worldwide in 1973, but mostly features events in the United States. According to tornado researcher Thomas P. Grazulis, documentation of tornadoes outside the United States was historically less exhaustive, owing to the lack of monitors in many nations and, in some cases, to internal political controls on public information. Most countries only recorded tornadoes that produced severe damage or loss of life. Consequently, available documentation in 1973 mainly covered the United States. On average, most recorded tornadoes, including the vast majority of significant—F2 or stronger—tornadoes, form in the U.S., although as many as 500 may take place internationally. Some locations, like Bangladesh, are as prone to violent tornadoes as the U.S., meaning F4 or greater events on the Fujita scale.

This page documents the tornadoes and tornado outbreaks of 1971, primarily in the United States. Most tornadoes form in the U.S., although some events may take place internationally. Tornado statistics for older years like this often appear significantly lower than modern years due to fewer reports or confirmed tornadoes.

The history of tornado research spans back centuries, with the earliest documented tornado occurring in 200 and academic studies on them starting in the 18th century. This is a timeline of government or academic research into tornadoes.