Montoneros was an Argentine far-left Peronist and Catholic revolutionary guerrilla organization, which emerged in the 1970s during the "Argentine Revolution" dictatorship. Its name was a reference to the 19th-century cavalry militias called Montoneras, which fought for the Federalist Party in the Argentine civil wars. Radicalized by the political repression of anti-Peronist regimes, the Cuban Revolution and socialist worker-priests committed to liberation theology, the Montoneros emerged from the 1960s Catholic revolutionary guerilla Comando Camilo Torres as a "national liberation movement", and became a convergence of revolutionary Peronism, Guevarism, and the revolutionary Catholicism of Juan García Elorrio shaped by Camilism. They fought for the return of Juan Perón to Argentina and the establishment of "Christian national socialism", based on 'indigenous' Argentinian and Catholic socialism, seen as the ultimate conclusion of Peronist doctrine.

Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín was an Argentine lawyer and statesman who served as President of Argentina from 10 December 1983 to 8 July 1989. He was the first democratically elected president after the 7-years National Reorganization Process. Ideologically, he identified as a radical and a social democrat, serving as the leader of the Radical Civic Union from 1983 to 1991, 1993 to 1995, 1999 to 2001, with his political approach being known as "Alfonsinism".

The Dirty War is the name used by the military junta or civic-military dictatorship of Argentina for the period of state terrorism in Argentina from 1974 to 1983 as a part of Operation Condor, during which military and security forces and death squads in the form of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance hunted down any political dissidents and anyone believed to be associated with socialism, left-wing Peronism, or the Montoneros movement.

The People's Revolutionary Army was the military branch of the communist Workers' Revolutionary Party in Argentina.

The Argentine Army is the land force branch of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic and the senior military service of Argentina. Under the Argentine Constitution, the president of Argentina is the commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces, exercising his or her command authority through the Minister of Defense.

Secretariat of Intelligence was the premier intelligence agency of the Argentine Republic and head of its National Intelligence System.

San Nicolás de los Arroyos is a city in the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina, on the western shore of the Paraná River, 61 km (38 mi) from Rosario. It has about 133,000 inhabitants. It is the administrative seat of the partido of the same name. It is sometimes called Ciudad de María due to a series of Marian apparitions that led to the erection of the Sanctuary in honor of Our Lady of the Rosary of San Nicolás that began during the 1980s and were approved by Bishop Cardelli of the diocese as "worthy of belief" in 2016.

Norberto Rafael Ceresole was an Argentine sociologist and political scientist, who identified himself with Peronism, left-wing militias and the ideas of his friends Robert Faurisson, Roger Garaudy and Ernst Nolte. He was accused throughout his life of being neo-fascist and antisemitic because of his Holocaust denial and hatred of Zionism, Israel and the Jewish community. He was a close confidant of Venezuela president Hugo Chavez.

The Carapintadas were a group of mutineers in the Argentine Army, who took part in various uprisings between 1987 and 1990 during the presidencies of Raúl Alfonsín and Carlos Menem in Argentina. The rebellions, while at first thought to be an attempt at a military coup, were staged primarily to assert displeasure against the civilian government and make certain military demands known.

Enrique Haroldo Gorriarán Merlo was an Argentine guerrilla leader, born in San Nicolás de los Arroyos, Buenos Aires Province.

Argentine Revolution was the name given by its leaders to a military coup d'état which overthrew the government of Argentina in June 1966 and began a period of military dictatorship by a junta from then until 1973.

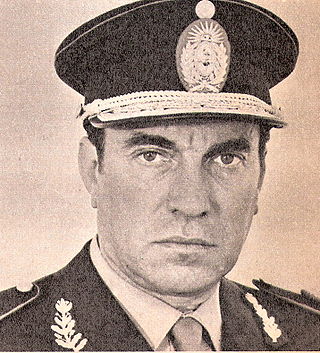

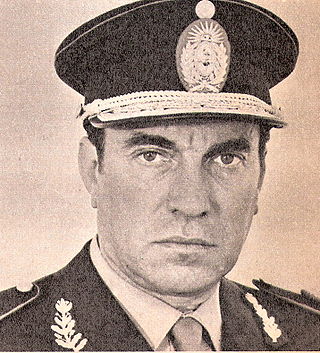

Antonio Domingo Bussi was an army general during the military dictatorship in Argentina and a politician prominent in the recent history of Tucumán Province, Argentina. He was tried and convicted for crimes against humanity.

Mohamed Alí Seineldín was an Argentine army colonel who participated in two failed uprisings against the democratically elected governments of both President Raúl Alfonsín and President Carlos Menem in 1988 and 1990.

The Trelew Massacre was a mass execution of 16 political prisoners, militants of different Peronist and leftist organizations, in Rawson prison by the military dictatorship of Argentina. The prisoners were recaptured after an escape attempt and subsequently shot down by marines led by Lieutenant Commander Luis Emilio Sosa in a simulated new attempt to escape. The marines forced the prisoners to fake a new escape, then executed them as revenge by the Revolución Argentina for the successful escape of some of their comrades during the initial prison break. The massacre took place in the early hours of 22 August 1972 in the Almirante Marcos A. Zar Airport, an Argentine Navy airbase located near the city of Trelew, Chubut in Patagonia.

The 601 Commando Company is a special operations unit of the Argentine Army.

Operation Primicia ("Scoop") was a large guerrilla assault that took place on 5 October 1975, in Formosa, Argentina. It was the largest attack ever launched by the paramilitary group Montoneros, which attempted to seize the barracks of the 29th Forest Infantry Regiment. The incident worsened the Dirty War, and indirectly led to the 1976 Argentine coup d'état the following year.

The Movimiento Todos por la Patria (MTP) was an Argentine leftist guerrilla movement active from 1986 to 1989, whose leader was Enrique Gorriarán Merlo. He was responsible for carrying out the 1989 attack on La Tablada Army Regiment.

Natalio Alberto Nisman was an Argentine lawyer who worked as a federal prosecutor, noted for being the chief investigator of the 1994 car bombing of a Jewish center in Buenos Aires, which killed 85 people, the worst terrorist attack in Argentina's history. On 18 January 2015, Nisman was found dead at his home in Buenos Aires, one day before he was scheduled to report on his findings before a Congress inquiry with supposedly incriminating evidence against high-ranking officials of the then-current Argentinian government including former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, regarding the Memorandum of understanding between Argentina and Iran.

Terrorism in Argentina has occurred since at least the 1970s, especially during the Argentine Dirty War, where a number of terror acts occurred, with support of both the democratic government of Juan Perón, Isabel Perón and the following de facto government of the National Reorganization Process. In the 1990s, two major terrorist attacks occurred in Buenos Aires, which together caused 115 deaths and left at least 555 injured.

In April 1987, members of the "Carapintadas", a faction within the Argentine Army, launched a mutiny against the civilian government of Raúl Alfonsín in response to trials of military officials for crimes committed during the period of military rule.