The World Food Programme (WFP) is an international organization within the United Nations that provides food assistance worldwide. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization and the leading provider of school meals. Founded in 1961, WFP is headquartered in Rome and has offices in 80 countries. As of 2021, it supported over 128 million people across more than 120 countries and territories.

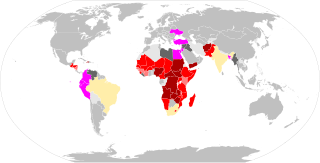

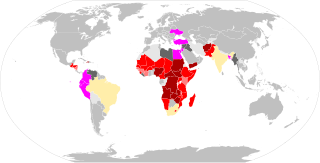

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accompanied or followed by regional malnutrition, starvation, epidemic, and increased mortality. Every inhabited continent in the world has experienced a period of famine throughout history. During the 19th and 20th century, Southeast and South Asia, as well as Eastern and Central Europe, suffered the greatest number of fatalities. Deaths caused by famine declined sharply beginning in the 1970s, with numbers falling further since 2000. Since 2010, Africa has been the most affected continent in the world by famine.

Famine relief is an organized effort to reduce starvation in a region in which there is famine. A famine is a phenomenon in which a large proportion of the population of a region or country are so undernourished that death by starvation becomes increasingly common. In spite of the much greater technological and economic resources of the modern world, famine still strikes many parts of the world, mostly in the developing nations.

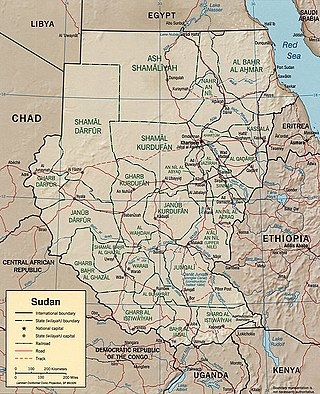

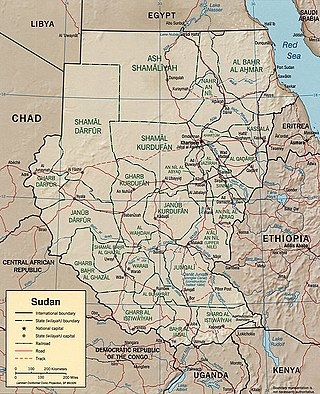

Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) was a consortium of United Nations agencies and approximately 35 non-governmental organizations operating in southern Sudan to provide humanitarian assistance throughout war-torn and drought-afflicted regions in the South. Operation Lifeline Sudan was established in April 1989 in response to a devastating war-induced famine and other humanitarian consequences of the Second Sudanese Civil War between the Sudanese government and South Sudanese rebels. It was the result of negotiations between the UN, the Government of Sudan and the Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) to deliver humanitarian assistance to all civilians in need, regardless of their location or political affiliation. This included over 100,000 returnees from Itang in Ethiopia in 1991. Lokichogio was the primary forward operations hub for OLS.

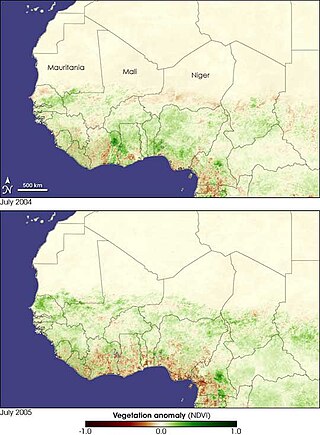

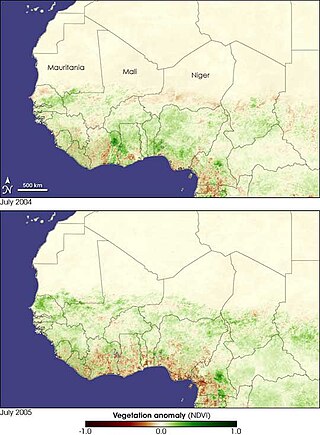

The 2005–2006 Niger food crisis was a severe but localized food security crisis in the regions of northern Maradi, Tahoua, Tillabéri, and Zinder of Niger from 2005 to 2006. It was caused by an early end to the 2004 rains, desert locust damage to some pasture lands, high food prices, and chronic poverty. In the affected area, 2.4 million of 3.6 million people are considered highly vulnerable to food insecurity. An international assessment stated that, of these, over 800,000 face extreme food insecurity and another 800,000 in moderately insecure food situations are in need of aid.

Various international and local diplomatic and humanitarian efforts in the Somali Civil War have been in effect since the conflict first began in the early 1990s. The latter include diplomatic initiatives put together by the African Union, the Arab League and the European Union, as well as humanitarian efforts led by the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), UNICEF, the World Food Programme (WFP), the Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF) and the Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS).

A large-scale, drought-induced famine occurred in Africa's Sahel region and many parts of the neighbouring Sénégal River Area from February to August 2010. It is one of many famines to have hit the region in recent times.

By January 2011 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that there are 262,900 Sudanese refugees in Chad. The majority of them left Sudan escaping from the violence of the ongoing Darfur crisis, which began in 2003. UNHCR has given the Sudanese refugees shelter in 12 different camps situated along the Chad–Sudan border. The most pressing issues UNHCR has to deal with in the refugee camps in Chad are related to insecurity in the camps,, malnutrition, access to water, HIV and AIDS, and education.

Occurring between July 2011 and mid-2012, a severe drought affected the entire East African region. Said to be "the worst in 60 years", the drought caused a severe food crisis across Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya that threatened the livelihood of 9.5 million people. Many refugees from southern Somalia fled to neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia, where crowded, unsanitary conditions together with severe malnutrition led to a large number of deaths. Other countries in East Africa, including Sudan, South Sudan and parts of Uganda, were also affected by a food crisis.

There were 795 million undernourished people in the world in 2014, a decrease of 216 million since 1990, despite the fact that the world already produces enough food to feed everyone—7 billion people—and could feed more than that—12 billion people.

Since 2016, a food insecurity crisis has been ongoing in Yemen which began during the Yemeni Civil War. The UN estimates that the war has caused an estimated 130,000 deaths from indirect causes which include lack of food, health services, and infrastructure as of December 2020. In 2018, Save the Children estimated that 85,000 children have died due to starvation in the three years prior. In May 2020, UNICEF described Yemen as "the largest humanitarian crisis in the world", and estimated that 80% of the population, over 24 million people, were in need of humanitarian assistance. In September 2022, the World Food Programme estimated that 17.4 million Yemenis struggled with food insecurity, and projected that number would increase to 19 million by the end of the year, describing this level of hunger as "unprecedented." The crisis is being compounded by an outbreak of cholera, which resulted in over 3000 deaths between 2015 and mid 2017. While the country is in crisis and multiple regions have been classified as being in IPC Phase 4, an actual classification of famine conditions was averted in 2018 and again in early 2019 due to international relief efforts. In January 2021, two out of 33 regions were classified as IPC 4 while 26 were classified as IPC 3.

In 2017 a drought ravaged Somalia that has left more than 6 million people, or half the country's population, facing food shortages with several water supplies becoming undrinkable due to the possibility of infection.

Poverty in Niger is widespread and enduring in one of the world's most impoverished countries. In 2015, the United Nations (UN) Human Development Index ranked Niger as the second least-developed of 188 countries. Additionally, in 2015 the Global Finance Magazine ranked Niger 7th among the twenty-three poorest countries in the world. Two out of three residents live below the poverty line and more than 40 percent of the population earn less than $1 a day. Civil war, terror, illness, disease, poverty and hunger plague Niger. Hunger is one of the most significant problems the population faces daily. With a national population of 19,899,120, 45.7% of this population live below the poverty line.

Food insecurity in Niger is a growing concern, with more than 1.5 million people affected in the year 2017.

Chad currently suffers from widespread food insecurity. A majority of the population of Chad now suffers some form of malnutrition. 87% of its population lives below the poverty line. Because the country is arid, landlocked, and prone to droughts, many Chadians struggle to meet their daily nutritional needs. While international aid into the country has brought some relief, the situation in Chad remains severe due to broader famine in the Sahel region. The World Food Programme has declared a state of emergency in the region since early 2018, stating that, “...adding to the poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition which already affects [the nations of the Sahel] to varying degrees, drought, failed harvests and the high prices of staple foods have hastened the arrival of this year’s ‘lean season’ – the worst since 2014.” Malnutrition is high, especially among women and children, with a significant majority of all children in Chad suffering from some form of stunted growth or adverse health effects as a result. As such, health in Chad is greatly affected by lack of food. Food insecurity is a symptom of broader instability in Chad, which suffers from political, ethnic, and religious instability. These issues have contributed to long-term food insecurity in Chad.

Long term aid to those in need creates a fear of having those provided with aid falling into the dependency theory. The rationale is that those who are benefiting will lose motivation to improve their lives on their own. Some may even work to worsen their condition in order to qualify for the aid. Additionally, one argument is that peripheral countries, such as Ethiopia, will not move out of needing aid because of the advanced economy's control. On average, Ethiopia has received 700,000 tons of food aid per year for the past 15 years. In rural Ethiopia, food aid has been provided for over three decades.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity has intensified in many places – in the second quarter of 2020 there were multiple warnings of famine later in the year. In an early report, the Nongovernmental Organization (NGO) Oxfam-International talks about "economic devastation" while the lead-author of the UNU-WIDER report compared COVID-19 to a "poverty tsunami". Others talk about "complete destitution", "unprecedented crisis", "natural disaster", "threat of catastrophic global famine". The decision of WHO on March 11, 2020 to qualify COVID as a pandemic, that is "an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people" also contributed to building this global-scale disaster narrative.

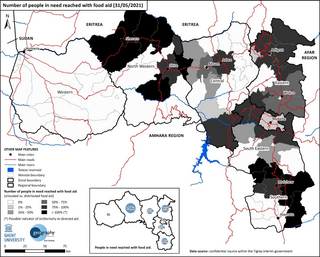

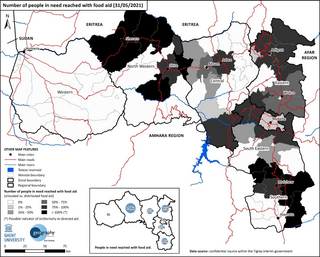

Beginning with the onset of the Tigray War in November 2020, acute food shortages leading to death and starvation became widespread in northern Ethiopia, and the Tigray, Afar and Amhara Regions in particular. As of August 2022, there are 13 million people facing acute food insecurity, and an estimated 150,000–200,000 had died of starvation by March 2022. In the Tigray Region alone, 89% of people are in need of food aid, with those facing severe hunger reaching up to 47%. In a report published in June 2021, over 350,000 people were already experiencing catastrophic famine conditions. It is the worst famine to happen in East Africa since 2011–2012.

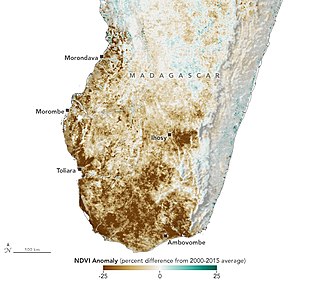

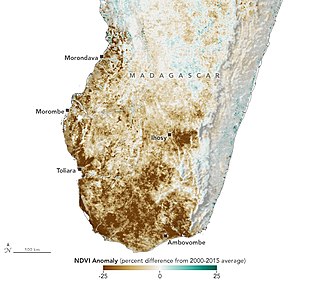

In mid-2021, a severe drought in southern Madagascar caused hundreds of thousands of people, with some estimating more than 1 million people including nearly 460,000 children, to suffer from food insecurity or famine. Some organizations have attributed the situation to the impact of climate change and the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country.

The 2020–2023 Horn of Africa drought is an ongoing drought that hit the countries of Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya. The rainy season of 2022 was recorded to be the driest in over 40 years, with an estimated 43,000 in Somalia dying in 2022. As of 2023, the region is now in its 5th failed rainy season and a 6th failed season is predicted.